In a groundbreaking achievement for observational astronomy, the European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope has successfully identified telltale signs of planets in the process of formation around 31 young stellar systems. This remarkable discovery represents a significant leap forward in our understanding of planetary genesis, offering astronomers an unprecedented window into the earliest stages of world-building across our galaxy. For decades, scientists have theorized about the mechanisms by which planets coalesce from the primordial material surrounding nascent stars, but directly observing this process has remained frustratingly elusive—until now.

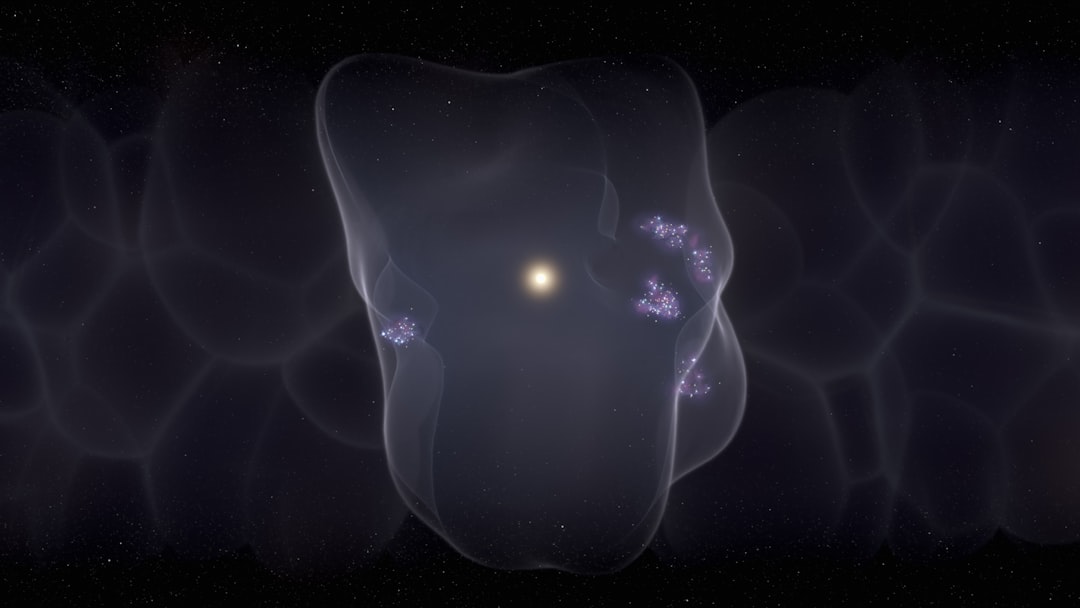

The research, led by Dr. Miguel Vioque at the European Southern Observatory, analyzed 98 young stellar systems using Gaia's extraordinary astrometric capabilities. What makes this achievement particularly remarkable is that these potential planets are still embedded within their natal protoplanetary discs—vast, swirling structures of gas and dust that serve as the cosmic nurseries where planetary systems take shape. These discs, while beautiful when captured by powerful telescopes, also serve as obscuring veils that make direct detection of forming planets extraordinarily challenging. The breakthrough demonstrates how precision astrometry, the science of measuring stellar positions and motions with extreme accuracy, can reveal hidden worlds that remain invisible to even our most powerful imaging systems.

The Challenge of Detecting Planetary Embryos

Understanding why finding planets around young stars is so difficult requires appreciating the chaotic environment of stellar birth. When a star forms from a collapsing cloud of molecular gas, it doesn't emerge as the stable, steadily-burning sphere we observe in mature systems like our Sun. Instead, young stars are temperamental objects, exhibiting dramatic variations in brightness, powerful stellar winds, and intense magnetic activity. They pulsate, flare, and fluctuate as they undergo the violent process of gravitational contraction and the initiation of nuclear fusion in their cores.

These inherent instabilities create significant noise in any measurement attempting to detect the subtle gravitational influence of a planet. The astrometric wobble caused by a planet's gravitational tug on its host star is minuscule—often just milliarcseconds, equivalent to measuring the width of a human hair from several kilometers away. When the star itself is dancing and gyrating due to its own internal dynamics, isolating the periodic, regular motion caused by an orbiting companion becomes exponentially more difficult. This is why, despite decades of planet-hunting efforts, very few confirmed exoplanets have been found around stars still in their formative years.

Adding to the challenge, protoplanetary discs themselves are optically thick at visible wavelengths. The same dust grains that will eventually aggregate into asteroids, comets, and planets scatter and absorb light, creating an obscuring curtain around the inner regions where rocky planets like Earth form. Our own Solar System condensed from such a disc approximately 4.6 billion years ago, but if alien astronomers had tried to observe Earth during its formation, they would have faced these same observational obstacles.

Gaia's Revolutionary Approach to Planet Detection

The Gaia space telescope, launched in 2013, wasn't specifically designed to hunt for planets—its primary mission is to create the most accurate three-dimensional map of our galaxy ever produced. However, the telescope's unprecedented precision in measuring stellar positions has opened unexpected avenues for discovery. Gaia operates by repeatedly scanning the entire sky, measuring the positions of over a billion stars with microarcsecond-level accuracy. By tracking how stars move relative to the distant background of galaxies, Gaia can detect even the tiniest perturbations in their motion.

The technique Vioque's team employed is known as astrometric detection, a method that has been used successfully to find planets around mature stars but never before applied systematically to young, forming systems. When a planet orbits a star, both objects actually orbit their common center of mass, called the barycenter. For a star with a massive planet, this causes the star to trace a small ellipse in space as the planet completes its orbit. Gaia's exquisite sensitivity allows it to detect these wobbles even when the planet itself remains completely invisible.

"What Gaia has accomplished here is truly remarkable. By applying astrometric techniques to young stellar systems, we're essentially watching planets being born in real-time across our galactic neighborhood. This opens an entirely new chapter in exoplanet science," explains Dr. Vioque in the research team's findings.

The power of Gaia's approach lies not just in its precision, but in its all-sky survey methodology. Ground-based searches for forming planets are resource-intensive, requiring dedicated telescope time and careful targeting of individual systems. Each observation campaign might study only a handful of stars. Gaia, by contrast, surveys the entire celestial sphere, enabling astronomers to study hundreds of young stellar systems simultaneously and build statistically meaningful samples for the first time.

A Census of Newborn Worlds and Their Companions

The results of this comprehensive survey reveal a fascinating diversity of companion objects around young stars. Out of the 31 systems showing clear evidence of unseen companions, the team identified three distinct populations based on the amplitude and characteristics of the stellar wobbles:

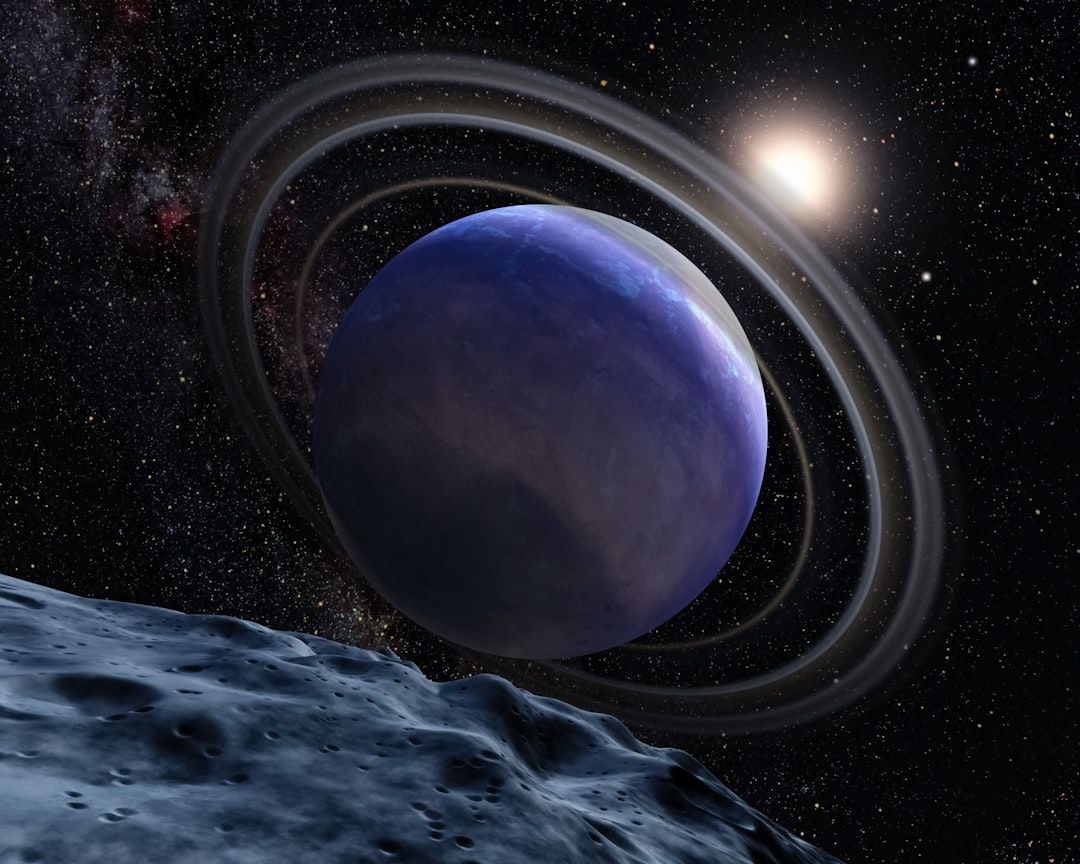

- Seven planetary-mass candidates: These systems exhibit motions consistent with companions in the planetary mass range, likely representing gas giants similar to Jupiter or Saturn in the process of formation. These objects are massive enough to gravitationally influence their host stars but fall below the threshold for sustained nuclear fusion.

- Eight brown dwarf candidates: These enigmatic objects occupy the twilight zone between planets and stars. With masses typically between 13 and 80 times that of Jupiter, brown dwarfs are sometimes called "failed stars" because they lack sufficient mass to sustain hydrogen fusion in their cores, though they may briefly fuse deuterium.

- Sixteen stellar companions: The remaining systems likely host additional stars in binary or multiple star configurations. These stellar companions are themselves in various stages of formation, creating complex gravitational environments where planet formation may be enhanced or suppressed.

The stunning visual representation released by ESA showcases these systems through imagery captured by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. ALMA's ability to observe at millimeter wavelengths allows it to penetrate the dust and reveal the intricate structure of protoplanetary discs. The images show glowing orange and purple rings and spirals—structures that may themselves be carved by the gravitational influence of forming planets. Gaia's predicted companion locations are marked in cyan, providing targets for future follow-up observations.

Implications for Planetary System Architecture

This discovery carries profound implications for our understanding of planetary system formation and evolution. By identifying planets at such early stages, astronomers can begin to address fundamental questions about the timeline of planet formation. How quickly do gas giants form? Do they migrate inward from distant orbits, as many theories suggest? What determines whether a protoplanetary disc produces multiple small rocky planets or a few massive gas giants?

The inclusion of a reconstructed image of our own Solar System at one million years old, with Jupiter's predicted orbit highlighted, provides crucial context. This comparison suggests that gas giant formation occurs relatively rapidly on cosmic timescales—within the first few million years of a star's life. Jupiter, our Solar System's dominant planet, likely formed during this early epoch and played a crucial role in shaping the architecture of the inner Solar System, influencing the distribution of material that eventually formed the terrestrial planets.

The diversity of companion types detected—planets, brown dwarfs, and stars—also highlights the continuum of outcomes possible from the same initial conditions. Understanding what factors determine whether a protoplanetary disc produces planets, brown dwarfs, or fragments into a binary star system remains one of the central questions in star and planet formation theory. The statistical sample provided by Gaia's survey will help astronomers build comprehensive models that can predict these outcomes based on initial disc properties.

Future Observations and the Next Generation of Discovery

Perhaps most exciting is that Gaia's detections provide a roadmap for follow-up observations with other cutting-edge facilities. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), with its powerful infrared capabilities, can peer through the dusty protoplanetary discs that hide forming planets from visible-light telescopes. JWST's instruments can detect the infrared glow of warm dust and gas surrounding young planets, map the chemical composition of protoplanetary discs, and potentially even image the planets themselves or the gaps they carve in the surrounding material.

Ground-based facilities like the Extremely Large Telescope currently under construction in Chile will also contribute to this effort. With a primary mirror 39 meters in diameter, this telescope will have the light-gathering power and resolution to directly image some of the companions Gaia has identified, revealing details about their atmospheres, temperatures, and ongoing formation processes.

The synergy between Gaia's all-sky astrometric survey and targeted follow-up observations represents a new paradigm in exoplanet research. Rather than searching blindly for planets, astronomers can now use Gaia's data to identify the most promising targets, then deploy specialized instruments to study them in detail. This efficient approach maximizes the scientific return from our most powerful and expensive telescopes.

Broader Context in the Search for Other Worlds

This breakthrough fits into the larger narrative of humanity's quest to understand our place in the cosmos. Since the first confirmed detection of an exoplanet around a Sun-like star in 1995, the field of exoplanetary science has exploded, with over 5,000 confirmed worlds now catalogued. However, the vast majority of these planets orbit mature stars, providing only snapshots of the end products of planet formation rather than the process itself.

By catching planets in the act of forming, Gaia is helping astronomers understand not just where planets are, but how they got there. This knowledge is essential for addressing profound questions about the prevalence of planetary systems in our galaxy, the likelihood of Earth-like worlds in habitable zones, and ultimately, the potential for life beyond our Solar System.

As Gaia continues its mission, now in its extended phase, it will accumulate even more precise measurements of stellar positions and motions. This will enable the detection of lower-mass planets and companions in wider orbits, further expanding our census of forming worlds. The combination of Gaia's ongoing survey with next-generation telescopes promises to transform our understanding of how planetary systems—including our own—come into being, evolve, and potentially harbor the conditions for life to emerge.