The formation of habitable, Earth-like worlds across the cosmos requires a delicate balance of conditions that scientists are only beginning to fully understand. A groundbreaking new study published in Science Advances reveals that cosmic ray bombardment from distant supernovae may be the missing ingredient that transforms ordinary rocky planets into potentially habitable worlds like our own. This research fundamentally reshapes our understanding of planetary formation and suggests that Earth-like planets might be far more common throughout the galaxy than previously thought.

The discovery addresses a long-standing puzzle in planetary science: how did our early solar system acquire the precise mixture of short-lived radioisotopes (SLRs) necessary to create a temperate, water-rich world? These radioactive elements, with half-lives shorter than 5 million years, played a crucial role in warming the nascent solar system and preventing Earth from becoming a waterlogged ocean world. Without this cosmic heating system, our planet might have evolved into something entirely different and potentially uninhabitable.

The Goldilocks Problem of Planetary Formation

Creating a truly Earth-like planet involves threading an extraordinarily narrow needle through cosmic conditions. A terrestrial world must accumulate sufficient mass to generate a protective magnetic field and retain a substantial atmosphere, yet remain small enough to avoid capturing excessive quantities of lightweight gases like hydrogen and helium that would fundamentally alter its composition. According to research from NASA's Planetary Science Division, this mass range represents only a small fraction of possible planetary outcomes.

The orbital positioning presents equally stringent requirements. A planet must orbit within its star's habitable zone—that precious region where temperatures allow liquid water to persist on the surface. Too close, and the world becomes a scorched, desiccated wasteland like Venus; too far, and it freezes into an icy tomb like Mars. But even achieving this perfect distance doesn't guarantee habitability, as researchers at the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute have discovered through decades of observation.

The third, often overlooked requirement involves the presence of adequate short-lived radioisotopes during the critical early formation period. These unstable atomic variants provide essential internal heating that drives geological activity, maintains a molten core for magnetic field generation, and crucially, prevents excessive water accumulation that would create Hycean worlds—planets with hydrogen-rich atmospheres and deep global oceans extending hundreds of kilometers beneath the surface.

Radioactive Fingerprints in Ancient Meteorites

Our understanding of the early solar system's radioactive composition comes from meticulous analysis of meteorite samples that preserve pristine records of conditions during planetary formation. Scientists have identified telltale signatures of now-extinct radioisotopes through their decay products embedded in these cosmic time capsules. The isotope aluminum-26, for instance, decays into magnesium-26 with a half-life of approximately 717,000 years—a geological instant.

When researchers detect anomalous concentrations of magnesium-26 in meteoritic minerals, they can calculate backward to determine how much radioactive aluminum must have been present 4.6 billion years ago when our solar system was forming. Similarly, excesses of calcium-44 reveal the former presence of titanium-44, another crucial short-lived radioisotope. These radioactive elements generated tremendous heat as they decayed, fundamentally shaping the thermal evolution of nascent planets.

"The isotopic signatures preserved in meteorites provide an unambiguous record that our early solar system was extraordinarily enriched in short-lived radioisotopes. The question has always been: how did these elements get there without destroying the protoplanetary disk in the process?"

The heat generated by these decaying isotopes served multiple critical functions. It helped drive planetary differentiation—the process by which heavier elements like iron sink to form a metallic core while lighter materials rise to create a rocky mantle and crust. This internal churning also regulated water content, allowing excess volatiles to escape rather than accumulating into planet-drowning oceans. Research published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science demonstrates how this thermal regulation was essential for Earth's eventual habitability.

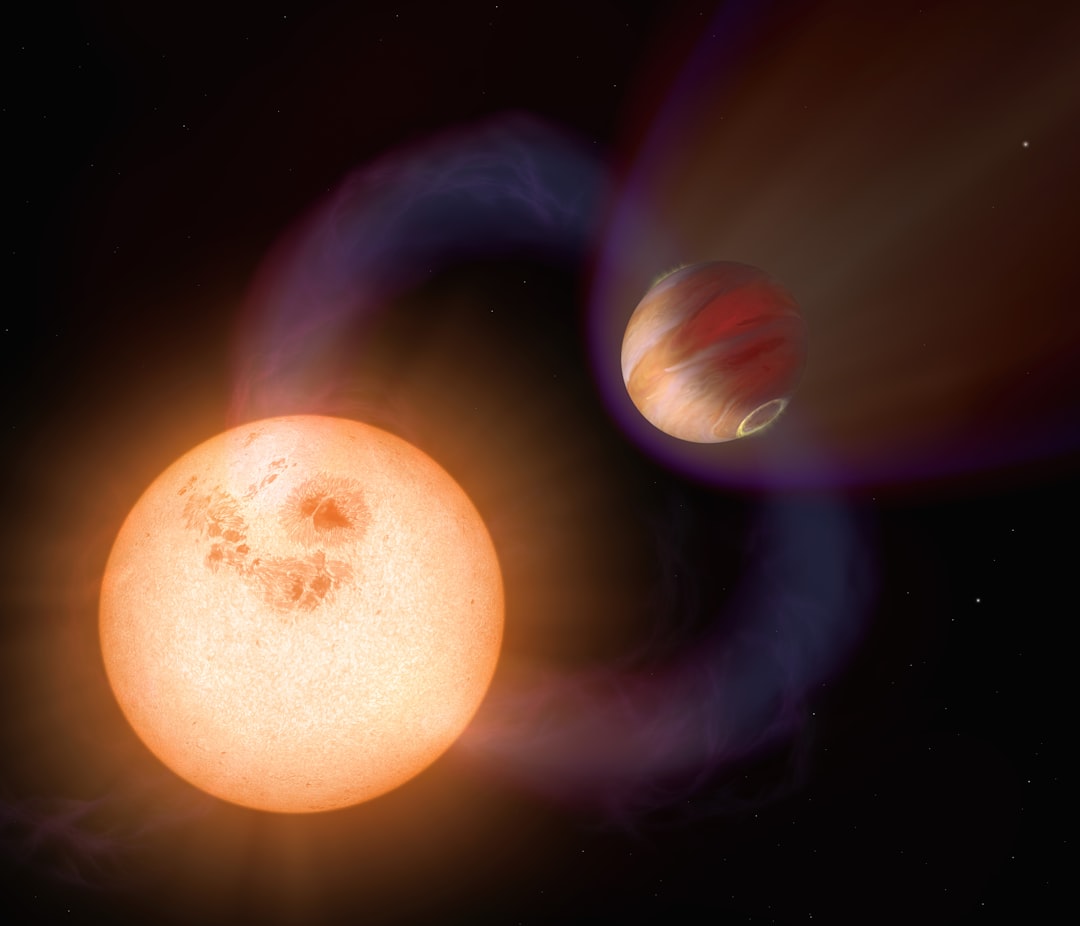

The Supernova Paradox: Creation Without Destruction

The origin of these short-lived radioisotopes presents a significant theoretical challenge. Supernova explosions represent the primary cosmic factories for producing these radioactive elements, forging them in the intense nuclear furnaces of dying massive stars. However, supernovae release such tremendous energy—equivalent to the Sun's entire lifetime output compressed into mere seconds—that a nearby explosion should theoretically obliterate a fragile protoplanetary disk rather than gently enriching it.

Previous models suggested that a supernova would need to detonate within a few light-years of our forming solar system to deliver sufficient radioisotopes. Yet such proximity would subject the protoplanetary disk to devastating shockwaves and intense radiation that would disperse the gas and dust before planets could coalesce. This apparent contradiction led some astronomers to conclude that Earth-like planets might be exceedingly rare cosmic accidents, requiring improbably precise circumstances.

If forming terrestrial worlds required surviving a nearby supernova's destructive fury intact, the statistical likelihood of Earth-like planets existing throughout the galaxy would plummet dramatically. This pessimistic scenario suggested that habitable worlds might be scattered so sparsely across the cosmos that interstellar civilizations would remain forever isolated by vast gulfs of empty space.

A Gentler Path: Cosmic Ray Enrichment

The new research by Sawada and colleagues proposes an elegant solution to this paradox. Rather than requiring a catastrophically close supernova, they demonstrate that cosmic ray bombardment from more distant stellar explosions could deliver the necessary radioisotopes without destroying the protoplanetary disk. Their sophisticated computer models show that supernovae occurring within approximately one parsec (3.26 light-years) would bathe a forming solar system in high-energy particles capable of generating short-lived radioisotopes through nuclear reactions.

These energetic cosmic rays—primarily protons and atomic nuclei accelerated to near-light speeds—interact with existing matter in the protoplanetary disk through a process called spallation. When high-energy particles collide with atoms of oxygen, silicon, and other elements, they can transmute them into radioactive isotopes like aluminum-26 and titanium-44. This mechanism provides a much more controlled delivery system than direct supernova ejecta.

The beauty of this model lies in its compatibility with stellar formation environments. Sun-like stars typically form within stellar nurseries—dense clusters containing hundreds or thousands of young stars. Within such crowded environments, massive stars evolve rapidly and explode as supernovae within a few million years. Statistical analysis shows that most forming solar systems would experience at least one nearby supernova during their critical early development phase, making cosmic ray enrichment a common rather than exceptional occurrence.

Observational Evidence Supporting the Model

The cosmic ray enrichment hypothesis gains support from galactic-scale observations of aluminum-26 distribution. Astronomers using space-based gamma-ray telescopes have mapped aluminum-26 concentrations throughout the Milky Way, revealing that this radioisotope remains continuously produced by ongoing supernova activity. The observed galactic abundance allows scientists to calculate the average supernova rate, which aligns remarkably well with the frequency required by the cosmic ray enrichment model.

Data from the European Space Agency's INTEGRAL observatory shows that aluminum-26 emission traces regions of active star formation and recent supernova activity. This distribution pattern supports the idea that forming planetary systems routinely encounter the cosmic ray environments necessary for radioisotope production. The consistency between theoretical predictions and observational data strengthens confidence in this new formation paradigm.

Implications for Planetary Habitability Across the Galaxy

This research dramatically revises upward our estimates for the prevalence of potentially habitable worlds. If cosmic ray enrichment represents a common process rather than a rare accident, then the fundamental ingredients for Earth-like planets exist throughout star-forming regions across the galaxy. The implications extend far beyond academic interest, touching on profound questions about humanity's place in the cosmos.

The study suggests that terrestrial planet formation follows a more universal pathway than previously imagined. Every stellar nursery producing Sun-like stars likely generates the conditions necessary for creating rocky, temperate worlds with appropriate water inventories and active geology. This universality implies that the galaxy may host billions of Earth-like planets, dramatically increasing the potential for life beyond our solar system.

Key Insights from the Research

- Cosmic Ray Mechanism: High-energy particles from distant supernovae can generate short-lived radioisotopes through nuclear spallation reactions without destroying protoplanetary disks, solving the long-standing paradox of radioisotope delivery.

- Statistical Probability: Computer simulations demonstrate that approximately 70-80% of Sun-like stars forming in typical stellar clusters would experience sufficient cosmic ray exposure to produce Earth-like radioisotope abundances.

- Thermal Regulation: The decay heat from cosmic-ray-produced radioisotopes prevents terrestrial planets from accumulating excessive water, maintaining surface conditions conducive to complex chemistry and potentially life.

- Galactic Distribution: Observations of aluminum-26 throughout the Milky Way confirm that the conditions for cosmic ray enrichment exist in star-forming regions across the galaxy, not just in our local neighborhood.

- Timeline Constraints: The enrichment must occur within the first few million years of solar system formation, when protoplanetary disks remain sufficiently massive and before terrestrial planets complete their accretion.

Future Research Directions and Observational Tests

While this model provides a compelling framework for understanding Earth-like planet formation, several avenues for future investigation remain open. Astronomers hope to test these predictions by examining isotopic compositions in other planetary systems, though such measurements lie at the edge of current technological capabilities. The next generation of extremely large telescopes may enable spectroscopic detection of radioisotope signatures in young protoplanetary disks around nearby stars.

Upcoming missions like the James Webb Space Telescope's detailed observations of planet-forming regions could reveal whether cosmic ray processing leaves detectable fingerprints in disk chemistry. Additionally, continued meteorite studies from our own solar system may uncover additional radioisotopes that further constrain the cosmic ray exposure our early solar system experienced.

The research also motivates renewed interest in understanding how stellar cluster environments influence planetary system characteristics. By studying the properties of exoplanets around stars with different formation histories, astronomers may be able to correlate cosmic ray exposure with planetary outcomes, providing direct observational validation of this formation mechanism.

As our census of exoplanets continues expanding through missions like TESS and future observatories, statistical studies of terrestrial planet occurrence rates will test whether the cosmic ray enrichment model accurately predicts the abundance of Earth-like worlds. If the model proves correct, it suggests that the galaxy teems with potentially habitable planets, each carrying the radioactive legacy of ancient supernovae that helped sculpt their destinies billions of years ago.