In the cold, dark nurseries where stars are born, astronomers have uncovered a phenomenon that defies conventional understanding of stellar formation. Deep within the Ophiuchus molecular cloud, approximately 450 light-years from Earth, the James Webb Space Telescope has detected something that shouldn't exist: ultraviolet radiation emanating from the vicinity of five infant protostars. These celestial newborns, still deeply embedded in their cosmic cradles of gas and dust, lack the extreme temperatures necessary to produce UV light—yet the evidence is unmistakable, challenging decades of established theory about how stars come into being.

This groundbreaking discovery, led by Dr. Agata Karska from the University of Torun and the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, represents a fundamental puzzle in our understanding of protostellar environments. The finding emerged from meticulous observations using JWST's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), which can peer through the obscuring dust clouds that shroud these young stellar objects. What the telescope revealed has forced astrophysicists to reconsider long-held assumptions about the conditions surrounding nascent stars and the complex physics governing their early evolution.

The Conventional Picture of Star Birth

To appreciate the significance of this discovery, we must first understand the traditional model of star formation that has guided astronomical research for decades. The process begins in vast molecular clouds—sprawling regions of space filled primarily with molecular hydrogen (H₂), the universe's most abundant molecule. These clouds, sometimes spanning hundreds of light-years, contain regions dense enough that their own gravity causes them to collapse inward.

As these dense cores contract, they fragment into smaller clumps, each destined to become an individual star or stellar system. The collapsing material forms a protostar at the center, surrounded by a rotating disk of gas and dust. During this earliest phase, which can last several hundred thousand years, the protostar remains relatively cool—typically below 3,000 Kelvin at its surface. At such temperatures, these infant stars should be incapable of generating ultraviolet radiation, which requires much hotter conditions typically found only in mature stars with surface temperatures exceeding 10,000 Kelvin.

According to established models, protostars emit primarily in the infrared spectrum, their feeble light further reddened by the dense cocoons of dust that envelope them. This is precisely why NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and now JWST have been so valuable for studying stellar birth—their infrared capabilities allow them to see through the obscuring material that blocks visible light.

An Unexpected Spectral Signature

When Dr. Karska's team analyzed the spectroscopic data from JWST's observations of the Ophiuchus protostars, they discovered unmistakable signatures of UV-excited molecular hydrogen in the outflows surrounding these young stars. The evidence came from studying the molecule's emission lines—specific wavelengths of light that H₂ emits when its electrons transition between energy levels.

"This is the first surprise. Young stars are not capable of being a source of radiation; they cannot 'produce' radiation. So we should not expect it and yet we have shown that UV occurs near protostars," explained Dr. Agata Karska, highlighting the fundamental challenge this discovery poses to existing theory.

Molecular hydrogen's importance in this research cannot be overstated. As the most abundant molecule in the universe, H₂ outnumbers even carbon monoxide—the second most common molecule—by a ratio of 10,000 to one. When UV photons strike H₂ molecules, they pump energy into the molecular structure in highly specific ways, creating distinctive patterns in the emitted light that serve as an unmistakable fingerprint of UV exposure. These signatures are fundamentally different from those produced by other excitation mechanisms, such as simple heating or collision with other particles.

The unprecedented sensitivity and spectral resolution of JWST's instruments allowed the research team to detect and analyze these subtle signatures with a precision impossible with previous generations of telescopes. The data revealed not just the presence of UV radiation, but provided clues about its intensity and spatial distribution around the protostars.

Hunting for the Source: Testing Multiple Hypotheses

Faced with this perplexing observation, the research team embarked on a systematic investigation to identify the source of the mysterious UV radiation. Their first hypothesis focused on external illumination from nearby massive stars. The Ophiuchus star-forming region contains numerous hot, luminous B-type stars scattered throughout the molecular cloud. These stellar behemoths, with surface temperatures ranging from 10,000 to 30,000 Kelvin, are prolific producers of ultraviolet radiation.

The team developed sophisticated models to calculate the expected UV flux at each protostar's location based on the positions and luminosities of all known B-type stars in the region. They cross-referenced these predictions with observations of dust properties in the intervening space, since interstellar dust grains efficiently absorb UV photons and re-emit the energy at longer, infrared wavelengths. This dust absorption creates a predictable relationship between UV exposure and infrared emission that can be measured and modeled.

However, when the researchers compared their predictions with the actual observations, a striking pattern emerged: all five protostars showed remarkably consistent UV signatures despite occupying vastly different positions relative to external UV sources. Some protostars were located in regions heavily shielded from external B-type stars, while others had more direct exposure. Yet the UV-excited molecular hydrogen signatures remained similar across all five objects.

This consistency effectively ruled out external illumination as the primary source. If nearby massive stars were responsible, the UV signatures should have varied dramatically based on each protostar's unique environment and the amount of intervening dust. The hypothesis had failed, forcing the team to look elsewhere for an explanation.

A Local Solution: Shock-Generated UV

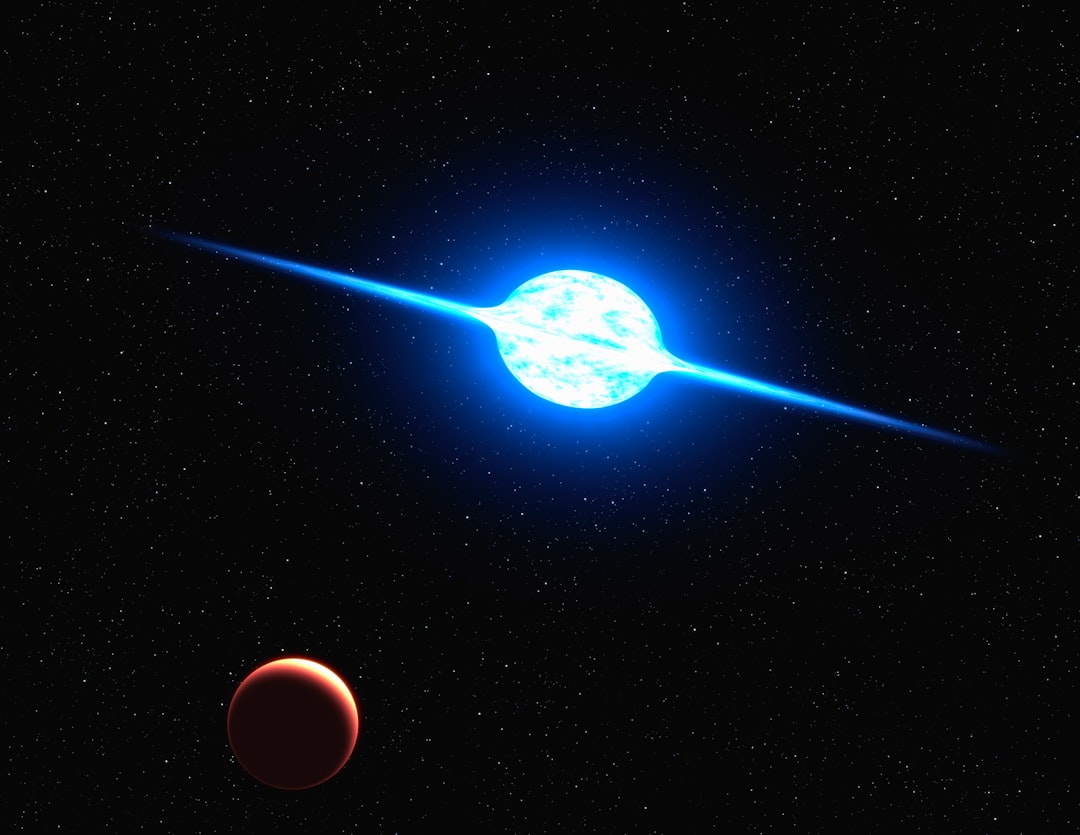

The researchers turned their attention to processes occurring much closer to the protostars themselves. Young stellar objects are known to be remarkably active, launching powerful jets and outflows as they accrete material from their surrounding disks. These outflows, which can extend for light-years into space, plow through the ambient molecular cloud at speeds reaching hundreds of kilometers per second.

When material moving at such velocities collides with slower-moving or stationary gas, it creates shock waves—violent discontinuities where gas is rapidly compressed and heated. These shocks can occur in multiple locations: where infalling material crashes onto the protostar's surface, within the jets themselves as faster material overtakes slower regions, or at the leading edge of the outflow as it bulldozes through the surrounding cloud.

The extreme conditions within these shock zones can generate temperatures of tens of thousands of Kelvin—hot enough to produce UV radiation. Additionally, the shocks can accelerate charged particles to high energies, creating conditions similar to those found in Herbig-Haro objects, which are known sites of energetic emission from young stellar systems.

Implications for Star Formation Theory

This discovery carries profound implications for our understanding of the physics and chemistry operating in protostellar environments. For decades, theoretical models of star formation have largely ignored or minimized the role of UV radiation during the earliest stages of stellar birth, operating under the reasonable assumption that such radiation shouldn't exist in these cold, embedded systems.

The presence of UV light in these regions fundamentally alters the chemical landscape. Ultraviolet photons are powerful agents of photodissociation—they can break apart complex molecules, resetting the chemistry to simpler forms. They also influence the ionization state of the gas, affecting how efficiently material can cool and collapse. These processes, in turn, impact the rate at which the protostar accretes mass and how quickly it evolves toward the main sequence.

Understanding the true UV environment around protostars is also crucial for predicting the composition of protoplanetary disks—the rotating structures of gas and dust from which planets eventually form. The molecules that survive in these disks, and their spatial distribution, depend critically on the radiation field they experience. If UV radiation is more prevalent than previously thought, it could explain puzzling observations about the chemistry of planet-forming disks observed around young stars.

Key Research Findings and Their Significance

- Universal UV Signatures: All five observed protostars in Ophiuchus showed evidence of UV-excited molecular hydrogen, suggesting this phenomenon may be a common feature of star formation rather than a rare occurrence

- Independence from External Sources: The consistency of UV signatures across different environmental conditions rules out external massive stars as the primary source, pointing to processes intrinsic to the protostars themselves

- Shock Wave Mechanism: The most likely explanation involves UV generation in shock waves created by protostellar jets and outflows, representing a previously underappreciated energy source in these systems

- Chemical Implications: The presence of UV radiation in protostellar environments requires revision of chemical models that predict molecular abundances and survival in star-forming regions

- Observational Breakthrough: JWST's MIRI instrument demonstrated unprecedented capability to detect and analyze molecular hydrogen emissions, opening new windows into the physics of stellar birth

The JWST Advantage: Peering Through Cosmic Fog

This discovery showcases the transformative capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope, which has revolutionized our ability to study star-forming regions since its launch. JWST's mid-infrared instruments, particularly MIRI, can observe wavelengths of light that pass relatively unimpeded through the dust clouds that obscure visible light from embedded protostars.

More importantly, JWST's spectroscopic capabilities allow astronomers to dissect the light from these objects into its component wavelengths with extraordinary precision. This enables the detection of subtle emission lines from molecules like H₂ that reveal the physical conditions—temperature, density, and radiation environment—in regions too small and distant to image directly. Previous infrared telescopes, including Spitzer, lacked the sensitivity and spectral resolution to detect these faint signatures with sufficient clarity to draw definitive conclusions.

The observations that led to this discovery are part of a broader campaign to study protostellar outflows using JWST. As more data becomes available from observations of star-forming regions throughout our galaxy, astronomers expect to refine their understanding of how common this UV phenomenon is and how it varies with protostellar properties such as mass, age, and outflow characteristics.

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

While this research has identified the presence of unexpected UV radiation around protostars, many questions remain unanswered. The precise mechanism by which shock waves generate this radiation requires further theoretical modeling and comparison with observations. Do different types of shocks—accretion shocks versus jet shocks—produce different UV intensities and spectra? How does the UV output vary as protostars evolve from their earliest embedded phase toward becoming visible pre-main-sequence stars?

Future observations with JWST and other facilities, including the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), will help answer these questions. ALMA's ability to map molecular emission with high spatial resolution can reveal the detailed structure of protostellar outflows, while JWST provides the UV-sensitive molecular diagnostics. Together, these observatories can paint a comprehensive picture of the energetics and chemistry in star-forming regions.

Theoretical astrophysicists are already working to incorporate these findings into updated star formation models. These revised models will need to account for UV radiation as a significant energy source and chemical agent in protostellar environments, potentially leading to new predictions about stellar masses, disk properties, and the efficiency of star formation in different galactic environments.

The discovery also highlights how much remains to be learned about even the most fundamental processes in astronomy. Star formation, while studied for over a century, continues to surprise us with unexpected phenomena that challenge our understanding. Each such surprise, like this mysterious UV radiation, pushes the field forward, forcing us to refine our theories and develop more sophisticated models that better match the complex reality of the universe.

As JWST continues its mission and returns more data from star-forming regions near and far, astronomers anticipate additional surprises that will further illuminate the intricate dance of gravity, radiation, and chemistry that transforms clouds of gas into the stars that light up our cosmos. This UV mystery inside newborn stars may be just the beginning of a new chapter in our understanding of stellar birth.