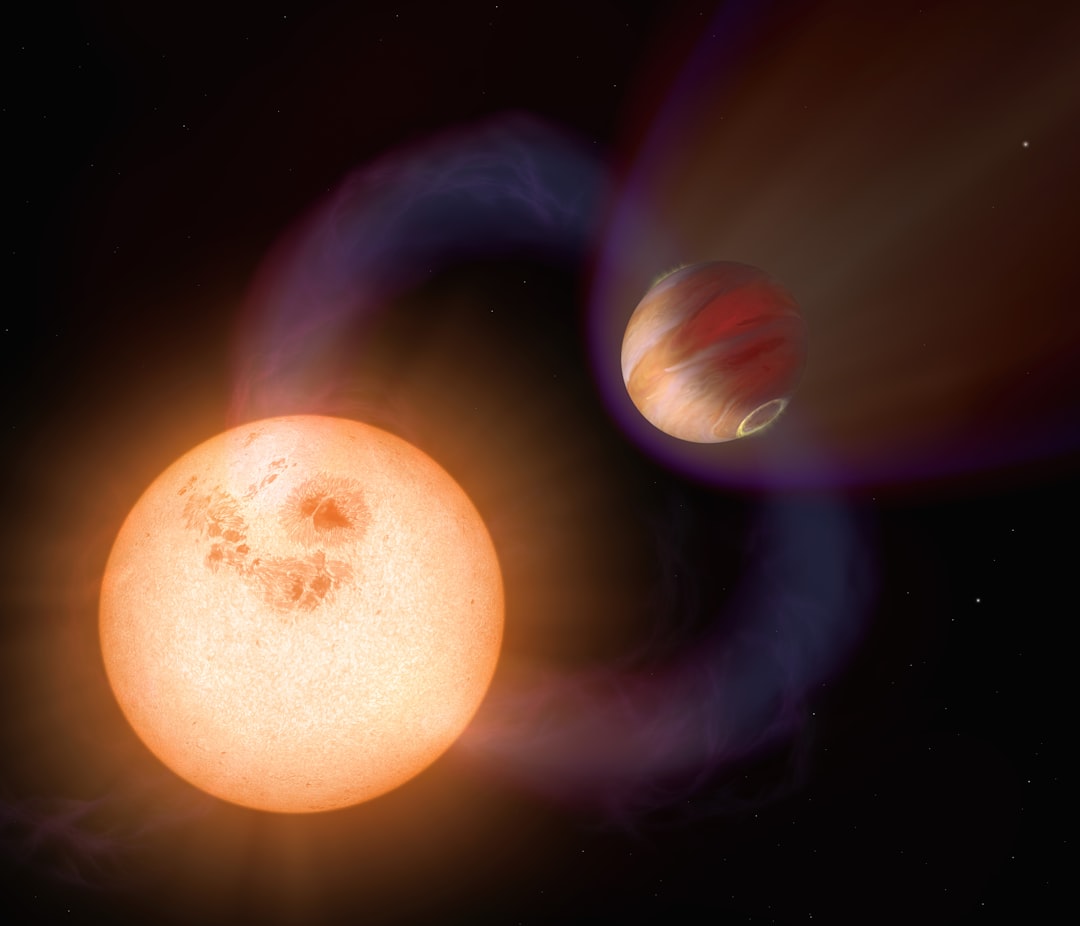

In the vast cosmic nursery of the Taurus constellation, approximately 350 light-years from Earth, astronomers have discovered a remarkable planetary system that's rewriting our understanding of how worlds are born. The V1298 Tau system, a mere 30 million years old—practically an infant in cosmic terms—hosts four extraordinarily unusual planets that researchers describe as "cotton candy worlds." These bloated, low-density giants represent one of the earliest snapshots of planetary evolution ever observed, offering scientists an unprecedented window into the chaotic early stages of planet formation.

A groundbreaking study recently published in Nature, one of the world's most prestigious scientific journals, has dramatically revised our understanding of these peculiar worlds. Led by John Livingston of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, the research team spent nine years collecting data from multiple space observatories to accurately measure the masses of these enigmatic planets—a feat that proved far more challenging than anyone anticipated. The results reveal that previous mass estimates were off by a staggering factor of 200 to 300 times, fundamentally changing how we interpret these young planetary systems.

What makes this discovery particularly significant is its potential to explain one of exoplanetary science's most persistent mysteries: the formation pathways of super-Earths and sub-Neptunes, the two most common types of planets found throughout our galaxy. By observing V1298 Tau in its infancy, astronomers are witnessing the evolutionary precursors to these ubiquitous worlds, essentially watching planetary adolescence unfold in real-time.

The Challenge of Weighing Infant Worlds

Measuring the mass of an exoplanet is never straightforward, but when dealing with a system as young as V1298 Tau, the challenges multiply exponentially. The system's host star, if compared to our Sun's lifecycle, would be equivalent to a five-month-old infant—temperamental, highly active, and covered in stellar blemishes. Young stars like V1298 Tau are notorious for their violent behavior, constantly erupting with stellar flares and covered in massive starspots that dwarf anything our Sun produces.

This youthful exuberance creates significant problems for astronomers using traditional planet-detection methods. The radial velocity technique, which typically measures how much a planet's gravity tugs on its host star, becomes unreliable when the star itself is thrashing about with magnetic activity. The stellar "noise" mimics and overwhelms the subtle gravitational signals that planets produce, leading to wildly inaccurate mass measurements—hence the initial overestimates by factors of hundreds.

To overcome this obstacle, Livingston's team employed an ingenious alternative approach called transit timing variations (TTVs). This method leverages the gravitational interactions between planets in a multi-planet system. As planets orbit their star, they don't follow perfectly regular paths; instead, they subtly tug on each other, causing slight variations in when they transit across their star's face. By meticulously tracking these tiny timing deviations over nine years using data from NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, TESS, Spitzer, and the Las Cumbres Observatory network, the researchers could accurately determine the planets' masses without being fooled by stellar activity.

"These cotton candy planets are so puffy and low-density that they challenge our conventional understanding of planetary physics. They represent a fleeting phase in planetary evolution that we're incredibly fortunate to observe," explains Dr. Livingston in the research paper.

Worlds as Fluffy as Carnival Treats

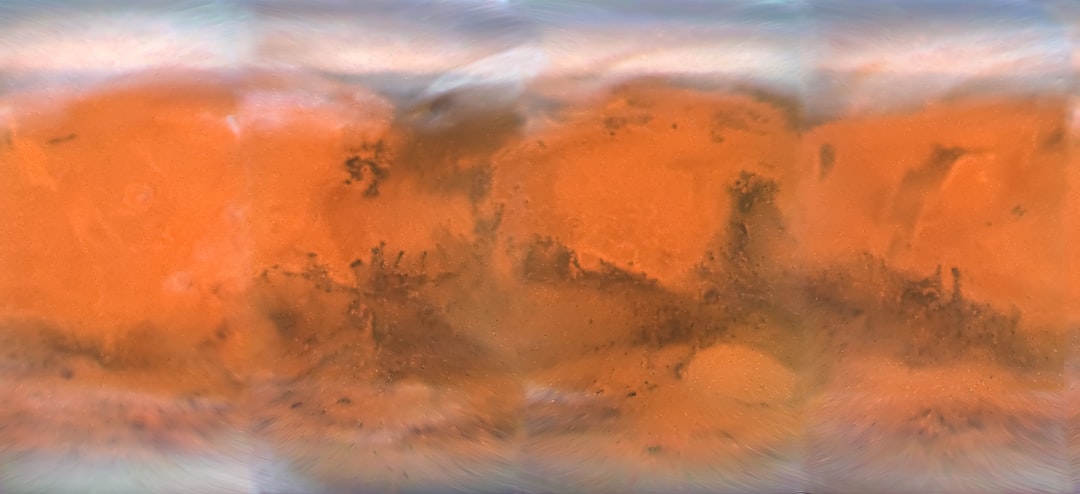

The four planets orbiting V1298 Tau are nothing short of extraordinary. Despite being roughly Jupiter-sized in radius, these worlds possess remarkably low masses, giving them densities comparable to confectionery treats. The least dense planet in the system has a density of merely 0.05 grams per cubic centimeter—literally equivalent to cotton candy. Another planet, despite being five times Earth's diameter, has the density of a marshmallow.

To put this in perspective, Earth has a density of 5.5 g/cm³, Jupiter clocks in at 1.3 g/cm³, and even Saturn, the least dense planet in our solar system, has a density of 0.7 g/cm³. The V1298 Tau planets are in a completely different category altogether—they're more atmosphere than solid material, with massive gaseous envelopes surrounding relatively small rocky or icy cores.

The TTV analysis also led to an unexpected bonus discovery: the team "recovered" a previously lost planet in the system. Earlier observations had detected this world, designated V1298 Tau b, but couldn't accurately determine its orbital period due to the star's activity. The new analysis revealed it completes an orbit every 48.7 days, bringing the confirmed planet count to four and making V1298 Tau one of the youngest known multi-planet systems.

A Cosmic Rosetta Stone for Planet Formation

The significance of V1298 Tau extends far beyond its individual peculiarities. Throughout the galaxy, surveys have revealed that the most common types of exoplanets fall into two distinct categories: super-Earths (rocky worlds with radii less than 1.5 times Earth's) and sub-Neptunes (gaseous planets around 2.0 times Earth's radius). Intriguingly, there's a conspicuous gap between these two populations—a mysterious absence of planets with radii between 1.5 and 2.0 Earth radii, known as the "radius valley" or "Fulton gap."

Scientists have long theorized that super-Earths and sub-Neptunes might share common origins, with sub-Neptunes eventually losing their puffy atmospheres to become super-Earths. V1298 Tau provides compelling evidence for this evolutionary pathway. These bloated young planets appear to be the ancestors of the mature super-Earths and sub-Neptunes we observe around older stars, caught in the act of transformation.

Three Mechanisms of Atmospheric Loss

The question of how these cotton candy worlds will evolve has profound implications for understanding planetary demographics across the galaxy. Astronomers have identified three primary mechanisms by which young planets shed their massive atmospheres:

- Photoevaporation: High-energy radiation from the host star—particularly extreme ultraviolet and X-ray photons—heats the upper atmosphere until gas molecules achieve escape velocity. This process, studied extensively by missions like the Hubble Space Telescope, can strip away entire atmospheric layers over millions to billions of years.

- Core-powered mass loss: Heat emanating from a planet's molten interior can drive atmospheric escape from below. As the rocky or icy core slowly cools and contracts, it releases tremendous energy that can push the overlying atmosphere outward into space. This mechanism operates on billion-year timescales.

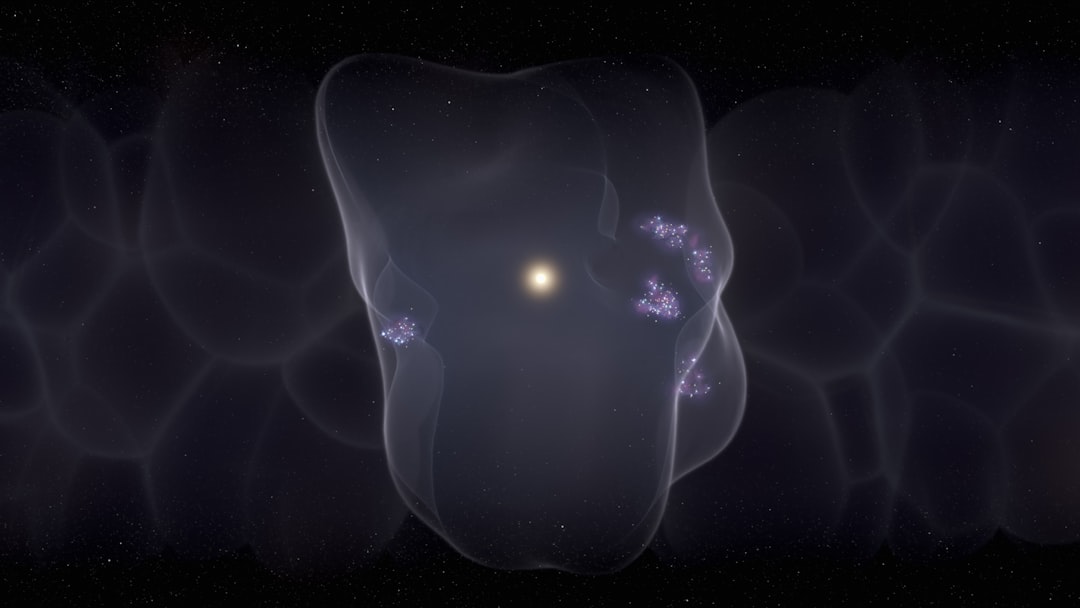

- Boil-off: This newly emphasized process occurs during the earliest stages of planetary evolution. When the protoplanetary disk—the rotating disk of gas and dust from which planets form—finally dissipates, it's like removing a pressure cooker's lid. The disk had been confining the planet's atmosphere; once it disappears, the atmosphere can explosively expand and escape into space. This rapid process may occur within just the first few million to tens of millions of years.

The research team's findings suggest that boil-off may be the dominant atmospheric loss mechanism for very young planets like those at V1298 Tau. This process operates much faster than photoevaporation or core-powered loss, potentially explaining why we don't observe many intermediate-stage planets—they transition relatively quickly from puffy sub-Neptunes to compact super-Earths.

Comparing Cosmic Siblings: V1298 Tau and Kepler-51

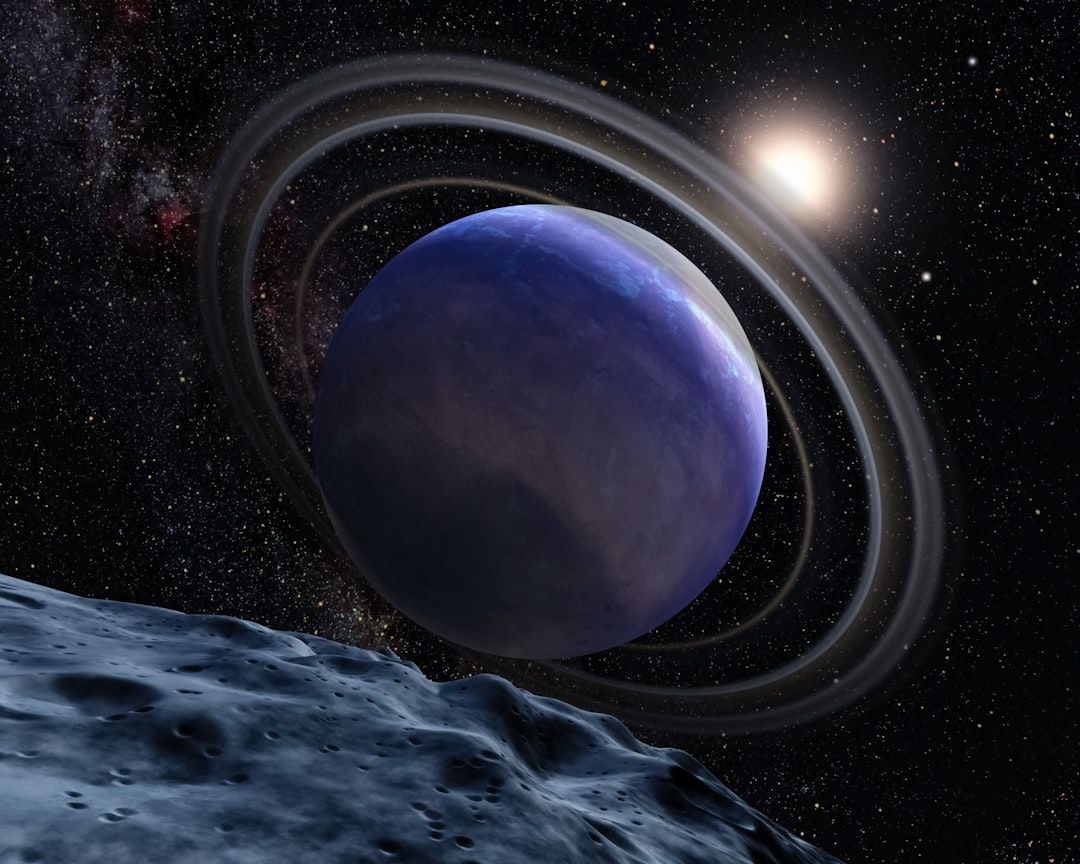

V1298 Tau isn't the only system hosting cotton candy planets. The Kepler-51 system, discovered earlier and studied extensively, also contains ultra-low-density worlds. However, Kepler-51 is approximately 400 million years old—more than ten times older than V1298 Tau. This age difference is crucial for understanding atmospheric evolution.

At 400 million years, Kepler-51's planets may have already completed the rapid boil-off phase and entered the slower photoevaporation regime. By contrast, V1298 Tau's extreme youth means we're observing planets potentially still undergoing boil-off, or having just recently completed it. This makes V1298 Tau an invaluable benchmark for testing theoretical models of early atmospheric loss.

The comparison between these two systems allows astronomers to construct a timeline of planetary evolution, essentially creating a cosmic growth chart for young worlds. Future observations with advanced facilities like the James Webb Space Telescope could directly measure atmospheric composition and loss rates, testing whether boil-off predictions match observations.

Implications for Planetary Habitability

While none of the V1298 Tau planets orbit in their star's habitable zone—the region where liquid water could exist on a planetary surface—understanding their evolution has profound implications for the search for life beyond Earth. Super-Earths in habitable zones around other stars are prime targets in the hunt for biosignatures, but their current rocky composition may belie more complex histories.

If many super-Earths began life as bloated sub-Neptunes before losing their atmospheres, this raises important questions: Did atmospheric loss strip away all volatiles, including water? Or could some water have been retained, potentially creating ocean worlds? The answers will shape how we prioritize targets for detailed atmospheric characterization with next-generation telescopes.

Additionally, the radius valley's existence suggests that planets just slightly larger than Earth might be fundamentally different worlds—not merely scaled-up versions of our home planet, but rather failed sub-Neptunes that lost most of their atmosphere. This distinction is critical for assessing habitability potential.

Future Directions in Young Planet Research

The nine-year observational campaign required to characterize V1298 Tau underscores both the challenges and opportunities in studying young planetary systems. As our exoplanet databases grow—with missions like ESA's CHEOPS and future surveys adding thousands more candidates—astronomers will likely discover even younger systems hiding in archival data.

The next frontier involves directly observing atmospheric escape in action. Spectroscopic observations during planetary transits can detect extended atmospheres and outflowing gas, providing real-time confirmation of mass loss processes. The James Webb Space Telescope's infrared capabilities are particularly well-suited for this work, as they can penetrate the dusty environments around young stars and detect molecular signatures in planetary atmospheres.

Moreover, theoretical models of boil-off and other atmospheric loss mechanisms need refinement. The V1298 Tau observations provide critical constraints on these models, but questions remain: How does the initial disk dispersal occur? What role do magnetic fields play in atmospheric retention? How do planetary composition and formation location affect subsequent evolution?

"V1298 Tau represents a milestone in our understanding of planetary demographics. By catching these planets in their infancy, we're finally able to test decades of theoretical predictions about how the galaxy's most common planets come to be," notes the research team in their Nature publication.

A Glimpse into Our Solar System's Past

Studying systems like V1298 Tau also offers insights into our own solar system's history. While our system lacks super-Earths and sub-Neptunes—making it somewhat unusual compared to typical planetary systems—the early evolution of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune likely involved similar atmospheric dynamics. Understanding how young gas giants interact with their natal disks and shed or retain their atmospheres helps reconstruct the chaotic early epochs of solar system formation.

The research also highlights how fortunate we are to observe V1298 Tau at this precise moment in cosmic history. In another few hundred million years, these cotton candy worlds will have transformed into something entirely different—denser, smaller, and more similar to the mature planets we typically observe. The window for observing this evolutionary phase is cosmically brief, making each young system we discover precious.

As exoplanetary science matures and our observational capabilities expand, discoveries like V1298 Tau remind us how much remains to be learned about planet formation and evolution. Each new system observed, each mass measurement refined, and each atmospheric spectrum obtained brings us closer to answering fundamental questions: How do planets form? Why do they look the way they do? And ultimately, how common are worlds like Earth in the vast expanse of the cosmos?

The V1298 Tau system, with its quartet of puffy, ephemeral worlds, stands as a cosmic laboratory—a place where theory meets observation, where predictions are tested, and where the story of planetary birth unfolds before our telescopes. As we continue to study this remarkable system and others like it, we're not just learning about distant worlds; we're decoding the fundamental processes that govern planet formation throughout the universe, including the origin of our own cosmic home.