The quest to identify potentially habitable exoplanets has captivated astronomers for decades, but a critical piece of the puzzle remains frustratingly elusive: understanding how stellar flares impact the conditions necessary for life. As our catalog of known exoplanets swells beyond 5,000 worlds, scientists are grappling with a sobering reality—many of the most promising candidates for harboring life orbit M dwarf stars, also known as red dwarfs, which unleash violent bursts of radiation that could render their planets sterile wastelands.

This challenge has taken on new urgency as researchers prepare for the next generation of exoplanet-hunting telescopes, including the European Space Agency's PLATO mission scheduled for launch in 2026. A groundbreaking white paper submitted to the European Southern Observatory's Expanding Horizons initiative, led by Dr. Rebecca Szabo from the Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, argues that without a comprehensive understanding of stellar flaring behavior, our ability to assess exoplanet habitability will remain fundamentally limited. The paper, titled "Habitability of exoplanets orbiting flaring stars," outlines an ambitious observational strategy that could finally break this scientific impasse.

The Red Dwarf Dilemma: Promise and Peril

Red dwarfs represent both the greatest opportunity and the most vexing challenge in the search for habitable worlds beyond our solar system. These diminutive stars, which comprise an astounding 70% of all stars in the Milky Way galaxy, burn their hydrogen fuel so slowly that they can shine for trillions of years—far longer than the current age of the universe. This remarkable longevity initially made them attractive targets for NASA's Kepler mission and other planet-hunting programs, as their stable, long-lived habitable zones seemed ideal for the slow processes of biological evolution.

Recent surveys have revealed that Earth-sized rocky planets are remarkably common around M dwarfs, with some estimates suggesting that virtually every red dwarf hosts at least one planet. However, the very characteristics that make these stars long-lived also create conditions hostile to life. Because red dwarfs are so small—typically between 8% and 50% of the Sun's mass—their habitable zones, where liquid water could exist on a planet's surface, lie extremely close to the star itself, often within a distance comparable to Mercury's orbit around our Sun.

This proximity places any potentially habitable planets directly in the crosshairs of the star's most violent outbursts. According to Szabo and her colleagues, "As of late 2025 there are about 70 exoplanets that meet the formal criterion of having equilibrium temperatures allowing the presence of liquid water and about 50 of them orbit M-stars, known for their strong chromospheric activity." This chromospheric activity includes not only powerful flares but also coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—massive eruptions of plasma and magnetic fields that can strip away planetary atmospheres over time.

The TRAPPIST-1 System: A Case Study in Flaring Concerns

Perhaps no stellar system better illustrates the habitability conundrum than TRAPPIST-1, located just 40 light-years from Earth. This ultracool red dwarf hosts seven Earth-sized rocky planets packed into an orbital configuration tighter than Mercury's path around our Sun. Three of these worlds—designated TRAPPIST-1e, f, and g—occupy the star's habitable zone, making them among the most tantalizing targets in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Yet observations from the James Webb Space Telescope and other facilities have revealed that TRAPPIST-1 is an active flare star, regularly unleashing bursts of high-energy radiation. The innermost planets are likely tidally locked, with one hemisphere perpetually facing the star and subjected to relentless bombardment by X-rays and extreme ultraviolet (EUV) radiation. Even the more distant planets in the habitable zone cannot escape entirely, as the stellar wind and energetic particles from flares can interact with and gradually erode planetary atmospheres.

Superflares: When Stars Unleash Unprecedented Energy

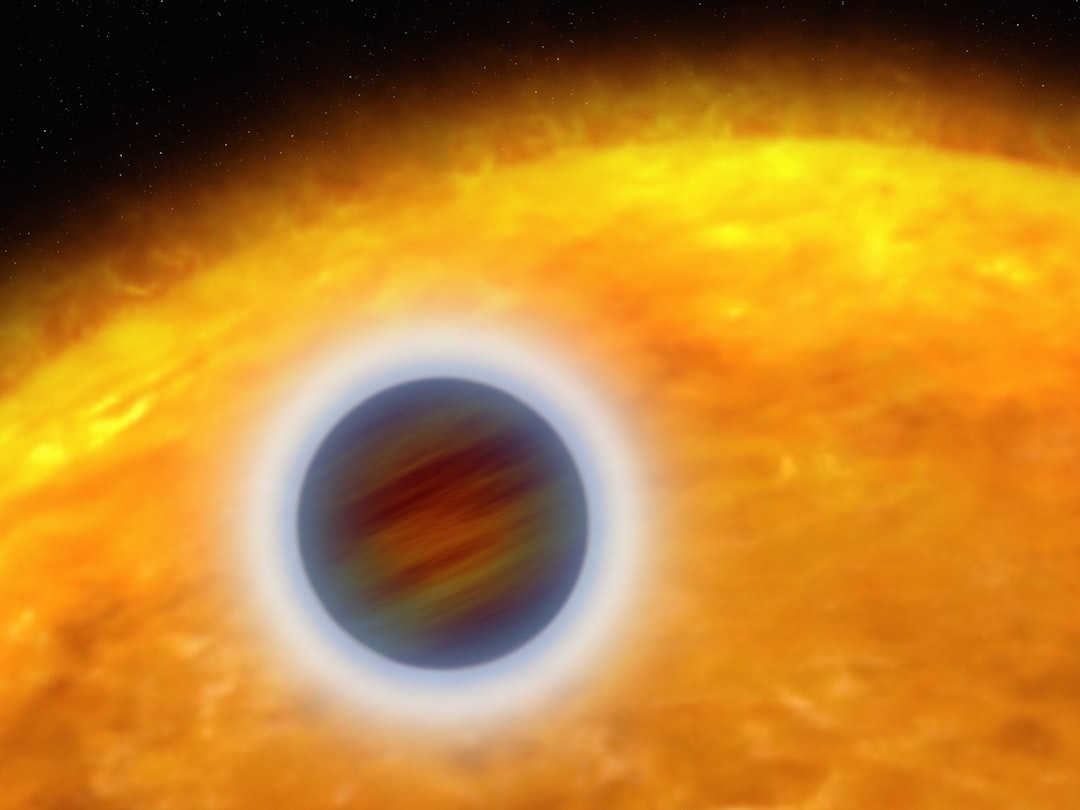

While all stars produce flares to varying degrees, some stellar outbursts defy conventional understanding. Superflares—defined as events releasing at least ten times more energy than the most powerful flares ever recorded from our Sun—have been observed on both red dwarfs and Sun-like G-type stars. These cataclysmic events can release energies equivalent to billions of hydrogen bombs detonating simultaneously, flooding nearby planets with lethal doses of radiation.

The white paper emphasizes that "impact of stellar activity on planetary environments and the potential for life require accurate estimates of flare energies. Radiation and particle outputs profoundly influence planetary atmospheres." Research published in 2019 demonstrated that high-energy flares occurring just once per month could completely destroy a planet's protective ozone layer within a few centuries. Without this crucial shield, surface life would be exposed to the full fury of the star's ultraviolet radiation, potentially sterilizing the planet entirely.

"The energy release during a typical flare is always accompanied with an emission of EUV and X-ray electromagnetic radiation, typically also accompanied by the eruption of hot solar plasma confined in a magnetic field—the coronal mass ejection," the authors explain, highlighting the multi-faceted threat that stellar activity poses to planetary habitability.

The Solar Advantage: Why We Know Our Star So Well

Our understanding of stellar flares is heavily skewed by our ability to study the Sun in exquisite detail. Multiple dedicated missions, including the Parker Solar Probe, which has ventured closer to our star than any previous spacecraft, and the Solar Dynamics Observatory, which monitors the Sun continuously across multiple wavelengths, provide an unprecedented window into stellar behavior. These missions have revealed the complex magnetic processes that drive solar flares and CMEs, tracking them from initiation through their journey across the solar system.

However, as Szabo's team notes, "spectroscopic information about flares on stars other than the Sun is sparse." While we can detect flares on distant stars through sudden increases in brightness, obtaining detailed spectroscopic data—which reveals the composition, temperature, and velocity of ejected material—remains extraordinarily challenging. This gap in our knowledge creates fundamental uncertainties about how stellar flares vary with stellar mass, age, and composition, making it difficult to predict which exoplanets might maintain habitable conditions despite their host star's activity.

A Telescope for the Flare-Finding Future

To address these critical knowledge gaps, the white paper proposes an ambitious observational program requiring a new class of telescope with specific capabilities. The authors outline two complementary observational strategies: continuous high-cadence monitoring of carefully selected late-type stars spanning different masses and ages, combined with rapid follow-up observations of stars exhibiting flares to capture detailed spectroscopic data during and after these events.

The proposed facility would need to meet several demanding technical requirements:

- Large Aperture: A primary mirror exceeding 4 meters in diameter to collect sufficient light from distant, faint red dwarf stars

- Wide Field of View: Approximately 1 to 3 degrees to monitor hundreds or thousands of stars simultaneously

- Extreme Multiplexity: The capability to observe multiple targets at once using approximately 30,000 optical fibers, each capturing the spectrum of an individual star

- High Cadence Monitoring: The ability to observe the same stars repeatedly over months or years to capture the full range of flaring behavior

- Rapid Response Capability: Quick follow-up observations when flares are detected to capture detailed spectroscopic information during these transient events

The authors point to China's Wide Field Survey Telescope (WFST), a 2.5-meter facility designed for time-domain astronomy, as a promising model. However, they argue that an even more capable instrument would be needed to fully address the flaring question across the diverse population of exoplanet hosts.

The Ultraviolet Paradox: Too Much and Too Little

Intriguingly, the relationship between stellar flares and habitability may not be entirely negative. Recent research has revealed a fascinating paradox: while excessive ultraviolet radiation can sterilize planetary surfaces, moderate UV exposure may actually be necessary for the formation of the prebiotic molecules that eventually gave rise to life on Earth. A 2018 study demonstrated that certain crucial biochemical reactions, including the formation of RNA building blocks, require specific wavelengths of UV light to proceed efficiently.

This discovery adds another layer of complexity to the habitability equation. Planets orbiting the quietest, most stable stars might actually lack the UV-driven chemistry necessary to kickstart biology, while worlds around moderately active stars could receive just the right amount of energetic radiation to foster prebiotic chemistry without destroying emerging life. As the white paper notes, "We can connect the prebiotic chemistry to the stellar ultraviolet (UV) spectrum to determine whether these reactions can happen on rocky planets around other stars."

This suggests that the "Goldilocks zone" for habitability may be more nuanced than previously thought, encompassing not just the right distance from the star for liquid water, but also the right level of stellar activity—enough to drive prebiotic chemistry, but not so much as to strip away atmospheres or sterilize surfaces. Understanding where this sweet spot lies for different types of stars requires the comprehensive flaring survey that Szabo and her colleagues advocate.

Collaboration Across Disciplines

The authors emphasize that understanding the biological implications of stellar flares will require unprecedented collaboration between astronomers and biologists. "This study will benefit from a collaboration with biologists working on extremophiles," they note, referring to organisms that thrive in Earth's most hostile environments—from the radiation-soaked pools near nuclear reactors to the UV-blasted peaks of high-altitude mountains.

Research into extremophiles has already revolutionized our understanding of life's resilience. Organisms like Deinococcus radiodurans, which can survive radiation doses thousands of times higher than would kill a human, demonstrate that life can adapt to conditions far more extreme than previously imagined. By studying how these organisms protect their DNA and repair radiation damage, scientists can develop more sophisticated models of which exoplanets might support life despite intense stellar activity.

The Road Ahead: Breaking the Impasse

As the number of known potentially habitable exoplanets grows from dozens to hundreds over the coming decade, the need for a comprehensive understanding of stellar flaring becomes increasingly urgent. Missions like ESA's PLATO telescope, scheduled for launch in 2026, will dramatically expand our catalog of Earth-sized planets in habitable zones. However, without parallel progress in understanding their host stars' activity, we risk compiling a list of worlds we cannot properly assess for their life-hosting potential.

The white paper concludes with a clear call to action: "A comprehensive study focused on properties of flaring exoplanet hosts and their activity, on a much larger scale than these few tens (soon to become hundreds) of stars with habitable planets is called for, to answer the question if such stars can harbor habitable planets." The proposed wide-field survey telescope, with its ability to monitor thousands of stars simultaneously while capturing detailed spectroscopic data during flare events, represents the most promising path forward.

This research will not only inform our search for life beyond Earth but also deepen our understanding of stellar physics, planetary atmosphere evolution, and the complex interplay between stars and their planetary systems. As we stand on the threshold of potentially detecting biosignatures in exoplanet atmospheres, understanding stellar flaring has never been more critical. The question is no longer whether we should undertake such a comprehensive survey, but rather how quickly we can build the instruments necessary to do so.

The search for habitable worlds continues, but as Szabo and her colleagues make clear, finding potentially habitable planets is only the first step. Understanding whether they can actually support life in the face of their host star's violent outbursts is the challenge that will define the next era of exoplanet science.