Cosmic Dust Bunnies: The Universe Might Be Fluffier Than We Thought

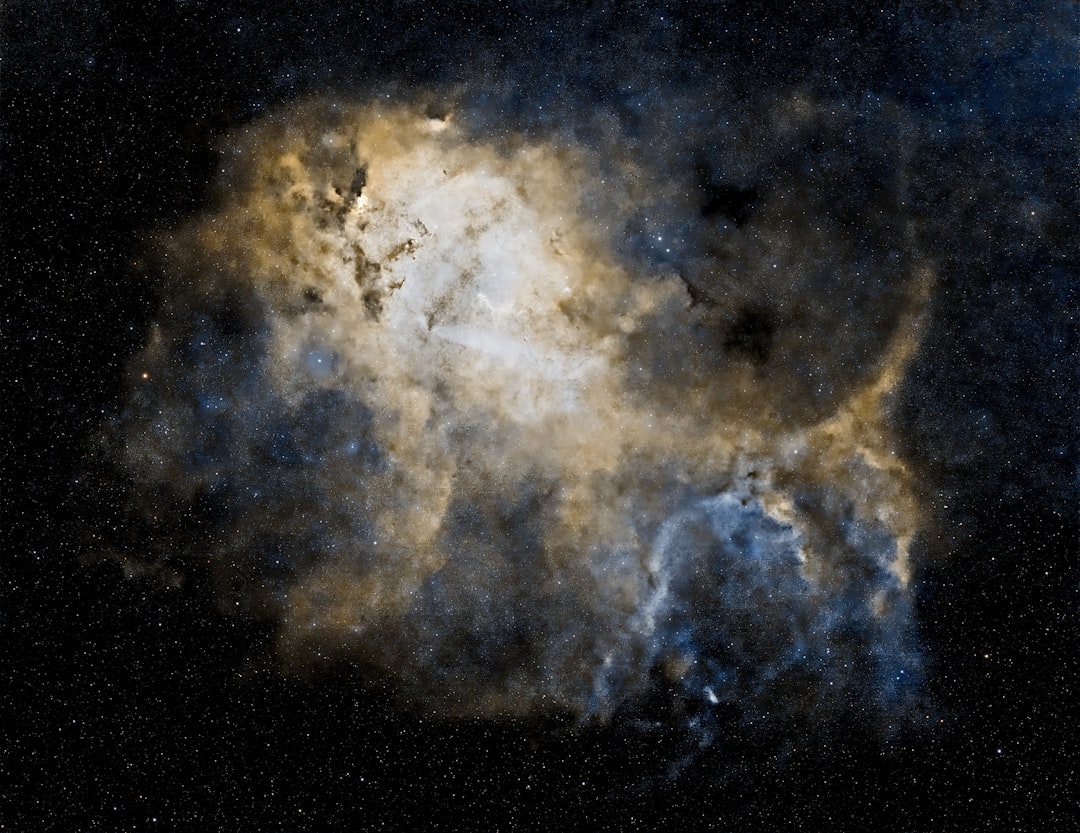

Space dust provides more than just awe-inspiring pictures like the Pillars of Creation. It can provide the necessary materials to build everything from planets to asteroids. But what it actually looks like, especially in terms of its "porosity" (i.e. how many holes it has) has been an area of debate for astrochemists for decades. A new paper from Alexey Potapov of Friedrich Schiller University Jena and his co-authors, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, suggests that the dust that makes up so much of the universe might be "spongier" than originally thought.

Why Does Dust Porosity Matter?

The porosity of cosmic dust is one of the main factors affecting the chemistry that goes on in interstellar clouds. Specifically, the surface area of dust available to act as a catalyst in important chemical reactions, such as the formation of H2, is drastically higher if the dust is "porous" rather than "compact", as it is in more traditional models. More porous dust also has ways of "trapping" volatiles in its structure, keeping them safe from the harsh conditions outside, and potentially allowing the dust particles themselves to ferry fragile substances like water to protoplanetary sites, such as the early Earth.

There are two different types of porosity when talking about the holes between particles of space dust:

- Intrinsic porosity: Intentional holes in the material itself, similar to a buckyball with a large hole in the middle of the structure.

- Extrinsic porosity: Gaps between particles that were smashed together as part of the gravitational pull between themselves.

Evidence for Porous Cosmic Dust

The authors base their argument on four different pieces of observational evidence:

- Dust samples collected by missions like Stardust and Rosetta

- Remote observations of the spectra of dust in the interstellar medium

- Experimental growth of synthetic dust in laboratories

- Simulations on both particle collision and atomistic scales

The Stardust mission, launched in 1999, passed through the coma of Comet Wild 2 and returned samples to Earth for analysis. Rosetta, launched in 2004, visited Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and studied its surroundings, including the dust forming its coma. Both missions found significant amounts of both "compact" and "porous" dust, with some porous samples reaching as high as 99% porosity.

Polarization studies of dust in the interstellar medium put slightly lower limits on the "fluffiness" of the dust particles. Data from an ALMA study of HL Tau put the porosity of the dust at around 90%, which the authors think might have been lowered by repeated inter-dust collisions compacting it down.

"The high porosity of cosmic dust has important implications for the chemistry and evolution of interstellar clouds and the formation of planetary systems," said lead author Alexey Potapov. "It could lead to more frequent chemical reactions and provide a mechanism for delivering water and other volatiles to young planets."

Laboratory Simulations and Modeling

Growing cosmic dust on Earth may seem counterintuitive, but researchers have attempted to do just that by using lasers to ablate rocks and then depositing the resulting gas and dust. In these laboratory simulations, the resulting deposition is always extremely porous, matching the data gathered by Rosetta and Stardust.

Modeling confirmed a similar amount of porosity, especially for "hit-and-stick" models of early dust interactions, which were particularly good at causing extrinsic porosity. Atomistic modeling also showed how having internal "micropores" on intrinsically porous samples could harbor water molecules and make them less likely to sublimate away in interplanetary space.

Implications and Future Research

While there is abundant anecdotal evidence for highly porous space dust, more data is needed to conclusively prove that most dust in space looks like a sponge rather than a solid pillar. If this is indeed the case, it could have significant implications for the chemistry and evolution of interstellar clouds and the formation of planetary systems.

Future missions, such as NASA's James Webb Space Telescope and the upcoming ESA's ARIEL mission, will provide even more detailed observations of cosmic dust, helping to further our understanding of its properties and role in the universe. If the high porosity of space dust is confirmed, perhaps someone will ask an AI to update the famous Pillars of Creation picture to add some noticeable holes to it.