The quest to discover Earth-like worlds capable of harboring life has taken a significant leap forward with the confirmation of five new exoplanets orbiting distant M-dwarf stars. This groundbreaking research, led by Jonathan Barrientos of the California Institute of Technology and detailed in a comprehensive paper on arXiv, reveals that at least two of these newly confirmed worlds may possess the precious commodity that makes atmospheric studies possible: retained atmospheres that survived the harsh stellar environment of their host stars.

Despite cataloging approximately 6,000 exoplanets to date, astronomers face a sobering reality—the vast majority of these distant worlds are unsuitable candidates for atmospheric characterization. Many lack atmospheres entirely, stripped away by intense stellar radiation. Others orbit stars too luminous for current telescope technology to effectively block out starlight and detect the faint spectral signatures of planetary atmospheres. Among those that remain, most are gas giants rather than the rocky, terrestrial worlds that could potentially support life as we know it. This new discovery provides critical additions to the relatively small pool of Earth-sized planets amenable to detailed atmospheric investigation.

The significance of this research extends beyond mere planetary census-taking. These five worlds represent carefully vetted targets for follow-up observations by humanity's most sophisticated space observatory, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which has revolutionized our ability to probe the chemical compositions of distant planetary atmospheres since its launch in 2021.

The TESS Discovery Pipeline: From Candidate to Confirmed World

The journey to confirm these five exoplanets began with NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), a space telescope specifically designed to scan the entire sky for planets crossing in front of their host stars. When TESS detects a periodic dimming of starlight—the telltale signature of a planet transiting its star—mission operators issue a TESS Object of Interest (TOI) alert to the global astronomical community. However, this initial detection represents only the first step in a rigorous confirmation process.

Converting a TOI candidate into a confirmed exoplanet requires extensive follow-up observations using multiple ground-based facilities. For this research, Barrientos and his international team coordinated observations from nine different telescopes, including prestigious facilities such as the Keck II Observatory in Hawaii and the historic Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory. This multi-instrument approach allowed researchers to perform detailed transit photometry—precise measurements of the starlight dips caused by planetary transits—and high-resolution imaging to rule out false positives such as background eclipsing binary stars.

The collaborative effort yielded confirmation of five planets distributed across four separate stellar systems. Intriguingly, one system hosts two planets locked in orbital resonance—a gravitational dance where the planets' orbital periods maintain a simple numerical ratio, similar to how Neptune and Pluto maintain a 3:2 resonance in our own solar system. This configuration provides valuable insights into the system's formation history and long-term dynamical stability.

Characterizing the New Worlds: Size, Mass, and Orbital Properties

The physical characteristics of these newly confirmed planets place them in the category astronomers call super-Earths—rocky worlds larger than our home planet but smaller than Neptune. Four of the five planets range from 1.28 to 1.56 times Earth's radius, while the fifth world, designated TOI-5716b, measures remarkably close to Earth's size. These dimensions are particularly exciting because planets in this size range likely possess rocky compositions with potential for solid surfaces, unlike the hydrogen-helium dominated gas giants that comprise many exoplanet discoveries.

However, these worlds differ dramatically from Earth in their orbital configurations. Their orbital periods—the time required to complete one revolution around their host stars—range from a mere 0.6 days to 11.5 days. To put this in perspective, the planet with the shortest period completes nearly 600 orbits in the time Earth completes just one. While these ultra-short periods might seem extreme, they reflect a fundamental observational bias in exoplanet detection: planets with shorter periods transit their stars more frequently, making them easier to detect and confirm with limited telescope time.

"The detection of Earth-sized and super-Earth planets around M-dwarf stars represents one of our best opportunities to characterize potentially habitable worlds beyond our solar system. These stars are numerous, relatively nearby, and their dimness makes atmospheric studies technically feasible with current technology."

The M-Dwarf Advantage and Challenge: A Double-Edged Sword

All five planets orbit M-dwarf stars—the smallest, coolest, and most common type of star in our galaxy. These red dwarf stars offer both tremendous advantages and significant challenges for exoplanet atmospheric studies. On the positive side, M-dwarfs emit relatively little light compared to Sun-like stars, making it substantially easier for advanced telescopes like JWST to block out stellar light while attempting to detect the faint spectral signatures of planetary atmospheres. This technical advantage has made M-dwarfs prime targets in the search for potentially habitable worlds.

However, M-dwarf stars harbor a dark side that threatens the very atmospheres astronomers hope to study. These stars are notoriously magnetically active, unleashing powerful X-ray and ultraviolet flares with energies far exceeding anything our Sun produces. According to research published in the Astrophysical Journal, these intense radiation bursts can effectively "sandblast" away planetary atmospheres, particularly for worlds orbiting close to their host stars where the radiation flux is most intense.

This atmospheric erosion process represents one of the most significant obstacles to habitability around M-dwarf stars. Even planets that form with substantial atmospheres may lose them over millions or billions of years of exposure to relentless stellar bombardment. Understanding which planets can retain their atmospheres despite this hostile environment has become a central question in exoplanet habitability research.

The Cosmic Shoreline: Mapping Atmospheric Survival

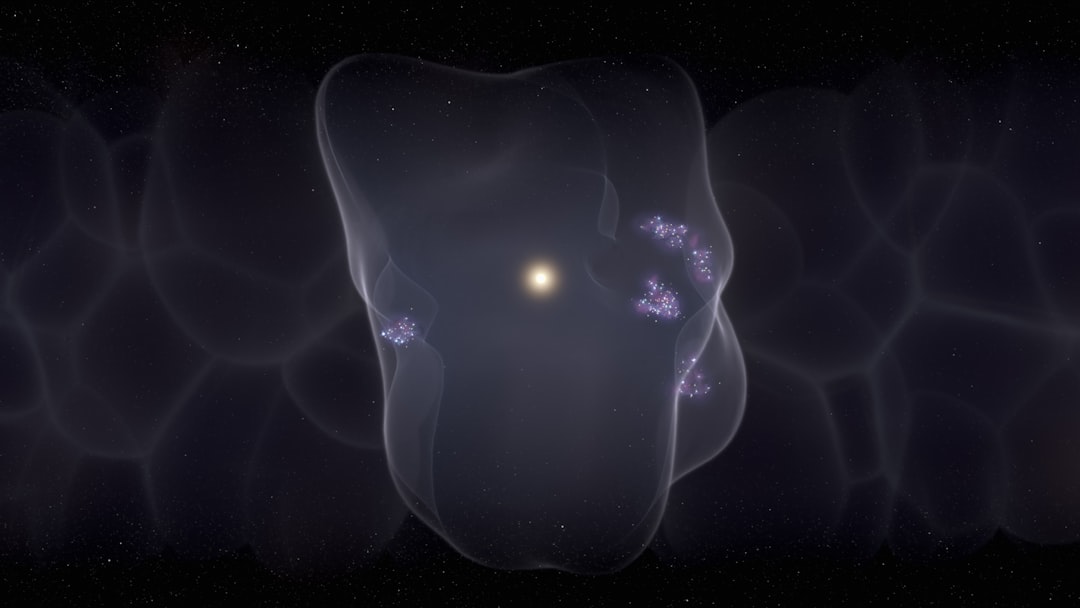

To predict which planets might retain atmospheres despite intense stellar radiation, astronomers have developed a concept called the "cosmic shoreline"—a boundary that separates worlds likely to retain atmospheres from those stripped bare by stellar radiation. This boundary emerges from plotting two critical parameters: the insolation (total radiation) a planet receives from its star against the planet's surface gravity.

The physics underlying this relationship is straightforward but profound. Higher insolation provides more energy to heat and strip away atmospheric gases, while stronger gravity—determined by a planet's mass and radius—helps a planet maintain its gravitational grip on those same gases. When astronomers plot known exoplanets on this two-dimensional graph, a remarkably clear linear boundary emerges, dividing atmospheric survivors from atmospheric casualties.

In the new study, Barrientos and colleagues categorized their five planets relative to this cosmic shoreline, revealing three distinct groups:

- Atmospheric Casualties: Three planets clearly fall "above" the cosmic shoreline, residing in the region where stellar radiation likely overwhelmed their gravitational retention. These worlds probably lost any primordial atmospheres they once possessed, leaving bare rocky surfaces exposed to space.

- The Massive Survivor: Planet TOI-5736b occupies a unique position. Despite receiving intense radiation due to its extremely short 0.6-day orbital period, its substantial mass and large radius suggest it might retain a volatile-rich atmosphere composed of heavier molecules that resist escape more effectively than lighter gases like hydrogen and helium.

- The Prime Candidate: Exoplanet TOI-5728b stands out as the study's most promising target. Despite orbiting an active M-dwarf star, this world's combination of moderate insolation and sufficient mass places it firmly below the cosmic shoreline—in the safe zone where atmospheric retention is expected.

TOI-5728b: A Prime Target for JWST Atmospheric Studies

Among the five newly confirmed worlds, TOI-5728b emerges as the most compelling candidate for detailed atmospheric characterization. This planet's position below the cosmic shoreline, combined with its M-dwarf host star's relative dimness, creates ideal conditions for direct atmospheric detection using transmission spectroscopy—a technique where astronomers analyze starlight filtered through a planet's atmosphere during transit to identify chemical signatures of atmospheric gases.

The James Webb Space Telescope has already demonstrated remarkable capability in detecting and characterizing exoplanet atmospheres, including the recent detection of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a hot gas giant and potential biosignature gases around other worlds. TOI-5728b's characteristics make it an excellent addition to JWST's target list for atmospheric reconnaissance.

However, the planet's 11.5-day orbital period—while relatively long compared to the other discoveries—still places it far too close to its star for comfortable habitability by Earth standards. The intense radiation and likely tidal locking (where one side perpetually faces the star) create extreme environmental conditions. Surface temperatures would likely be inhospitable to complex life as we know it, though certain extremophile microorganisms—organisms that thrive in Earth's most hostile environments—might potentially survive if protected by subsurface habitats or thick atmospheric shielding.

The Broader Context: Building a Census of Potentially Habitable Worlds

This research exemplifies the systematic, multi-stage process that characterizes modern exoplanet science. The pipeline begins with wide-field surveys like TESS identifying candidates, proceeds through ground-based confirmation campaigns using multiple telescopes, and culminates in detailed characterization by premium facilities like JWST. Each stage filters and refines our understanding, gradually building a comprehensive census of worlds beyond our solar system.

The discovery also highlights the importance of M-dwarf planetary systems in the search for life beyond Earth. Despite the challenges posed by stellar activity, M-dwarfs' abundance—they comprise roughly 75% of all stars in the Milky Way—means that most potentially habitable planets in our galaxy likely orbit these small red stars. Understanding the conditions under which M-dwarf planets can retain atmospheres and potentially support life remains one of astrobiology's most pressing questions.

Recent research from the European Southern Observatory has revealed that some M-dwarf systems may be more benign than previously thought, with stellar activity declining as stars age. This finding offers hope that older M-dwarf systems might harbor more stable environments conducive to long-term atmospheric retention and potentially even biological evolution.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Atmospheric Characterization

While TOI-5728b and its companions await their turn in JWST's busy observation queue, the groundwork laid by this confirmation study ensures that when observation time becomes available, astronomers will be ready to maximize the scientific return. The detailed characterization of these planets' masses, radii, and orbital parameters provides essential context for interpreting future atmospheric observations.

The coming years promise exciting developments in exoplanet atmospheric science. JWST continues to accumulate observation time on carefully selected targets, building a library of atmospheric spectra that will reveal the chemical compositions, temperature structures, and potentially even weather patterns of distant worlds. Each new atmospheric detection refines our understanding of planetary formation, evolution, and the factors that determine habitability.

Beyond JWST, next-generation facilities currently in planning stages—including extremely large ground-based telescopes and potential future space missions—will push atmospheric characterization to even smaller, more Earth-like planets orbiting at greater distances from their host stars. These future observations may finally answer humanity's age-old question: Are we alone in the universe?

For now, the five newly confirmed planets represent valuable additions to the growing catalog of worlds amenable to atmospheric study. As the wheels of science continue turning, each discovery brings us incrementally closer to understanding the true diversity of planetary systems and, perhaps, to finding evidence of life beyond Earth. The patient, methodical work of researchers like Barrientos and his colleagues—coordinating observations across multiple facilities, carefully analyzing data, and rigorously confirming each discovery—embodies the scientific process at its finest, gradually illuminating the cosmic landscape one planet at a time.