In a groundbreaking observation that pushes the boundaries of our understanding of planetary system formation, the James Webb Space Telescope has captured the first-ever detection of ultraviolet-fluorescent carbon monoxide within a protoplanetary debris disc. This remarkable discovery, led by astronomer Cicero Lu from the Gemini Observatory and detailed in a recent pre-print publication, provides unprecedented insights into the violent processes occurring in the inner regions of young stellar systems—processes that may fundamentally shape the composition of rocky planets like Earth.

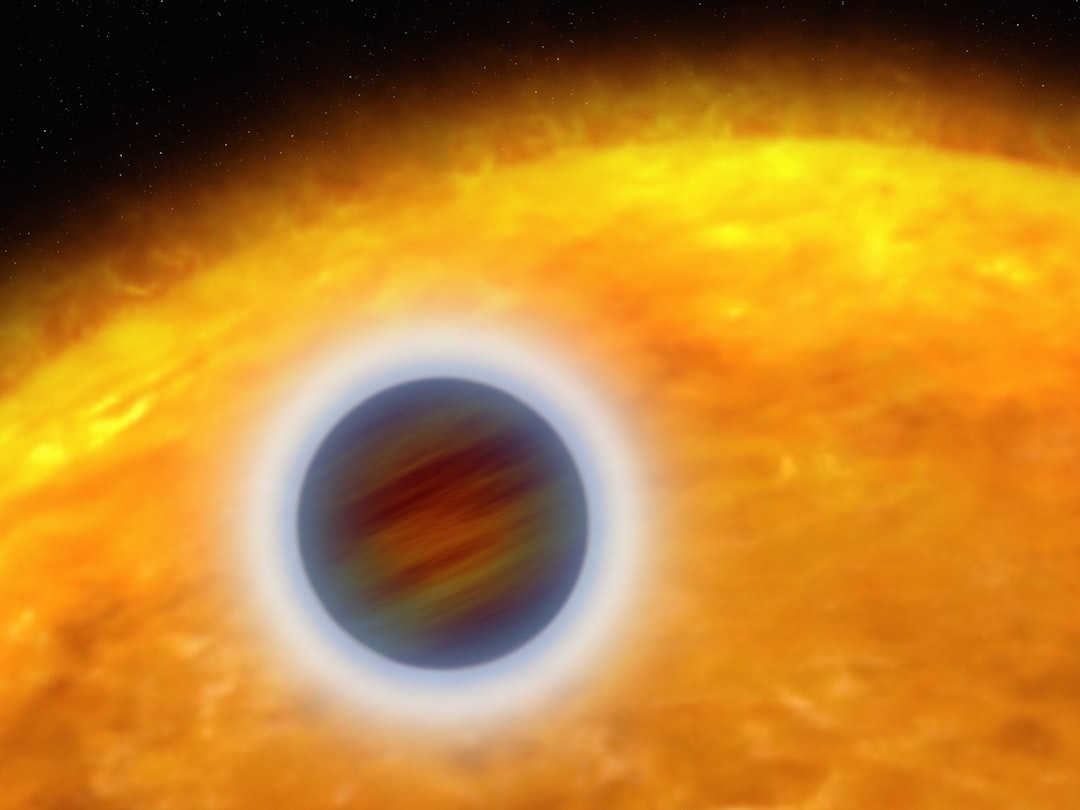

The target of this investigation, HD 131488, is a relatively youthful star approximately 15 million years old, located roughly 500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Centaurus. As an early A-type star, HD 131488 burns considerably hotter and more massive than our Sun, making it an ideal laboratory for studying the dynamic and often turbulent early stages of planetary system evolution. What makes this discovery particularly significant is not just the detection itself, but the wealth of information it reveals about how planetary building blocks are distributed and processed in the harsh radiation environment close to young stars.

This observation represents yet another triumph for humanity's most sophisticated space observatory, demonstrating JWST's unparalleled capability to peer into the infrared spectrum where crucial signatures of planetary formation processes become visible. The telescope's findings challenge existing theories and provide compelling evidence for one of astronomy's most debated questions: how do carbon monoxide-rich debris discs maintain their gas content over millions of years?

A Star System Under Intense Scrutiny

HD 131488 belongs to the Upper Centaurus Lupus subgroup, a stellar association that has become a prime target for astronomers studying young planetary systems. This isn't the first time this particular star has attracted scientific attention. Previous observations using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which operates at radio frequencies, had already revealed a substantial reservoir of cold carbon monoxide gas and dust particles distributed between approximately 30 and 100 astronomical units (AU) from the star—a region comparable to the distance from our Sun to Neptune and beyond.

Earlier infrared observations from ground-based facilities, including the Gemini Observatory and NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF), had provided tantalizing hints of hot dust and solid-state materials lurking in the star's inner zone. Even more intriguingly, optical spectroscopy studies had detected signatures of hot atomic gases, particularly calcium and potassium, in the inner disc region. However, these atomic species are fundamentally different from molecular carbon monoxide, which consists of atoms bonded together in a specific configuration.

What remained elusive until now was a comprehensive understanding of the molecular gas content in the star's inner regions—the zone where terrestrial planets like Earth, Venus, and Mars would form in a solar system analogous to our own. This is precisely where JWST's infrared capabilities proved invaluable, filling a critical observational gap that has puzzled astronomers for years.

The Power of Infrared Spectroscopy Revealed

During what was likely only an hour-long observation session in February 2023, JWST's Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument detected something remarkable: a small but significant quantity of "warm" carbon monoxide gas in the inner regions of HD 131488's disc. While this warm gas represents only about one hundred-thousandth of the mass of the cold gas reservoir in the outer disc, its presence and characteristics tell a fascinating story about the physical conditions in this region.

The warm CO gas is distributed between approximately 0.5 AU and 10 AU from the star—a zone that, in our own solar system, would encompass the orbits of Mercury through Saturn. What makes this gas particularly interesting are its unusual thermal properties. The molecules exhibit a dramatic disparity between two different types of temperature measurements: vibrational temperature and rotational temperature.

"The vibrational temperature represents how rapidly the atoms within each carbon monoxide molecule oscillate back and forth, while the rotational temperature indicates how fast the entire molecule spins through space—analogous to the molecule's kinetic energy," explains the research team in their paper.

In a typical gas at local thermal equilibrium—such as the air in a room—these two temperatures would be identical, equalized through countless molecular collisions. However, around HD 131488, the researchers discovered an extraordinary temperature discrepancy. The CO molecules' rotational temperature reaches only about 450 Kelvin at maximum (dropping to approximately 150K farther from the star), while their vibrational temperature soars to a blistering 8,800 Kelvin—matching the intense ultraviolet radiation emanating from the host star itself.

Cosmic Collisions: The Exocometary Connection

This dramatic thermal disequilibrium provides crucial clues about the origin of the warm gas. The researchers also discovered that the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-13 isotopes was unusually high for this type of environment, suggesting the presence of dust grains embedded within the sparse warm gas cloud, partially blocking and filtering the starlight. Additionally, to produce the specific light emission pattern detected by JWST, carbon monoxide molecules require "collisional partners"—other molecules that interact with them, transferring energy through impacts.

The research team investigated two potential collision partners: molecular hydrogen and water vapor. Their analysis strongly favors water vapor from disintegrating comets as the more likely candidate. This "exocometary hypothesis" represents one of the paper's most significant conclusions and addresses a long-standing astronomical debate.

Scientists have puzzled over the nature of these relatively rare CO-rich debris discs for years, proposing two competing explanations for how they maintain their gas content. The first hypothesis suggests that these discs are simply primordial remnants left over from the star's formation, gradually dissipating over time. The second proposes that the gas is continuously replenished through the destruction of comets—icy bodies that release their volatile contents when they venture too close to the star or collide with other objects.

The JWST observations of HD 131488 provide compelling evidence firmly supporting the second scenario. The characteristics of the warm CO gas—its thermal properties, spatial distribution, and chemical composition—are all consistent with a population of exocomets being vaporized by the star's intense radiation or destroyed in high-velocity collisions, continuously releasing fresh carbon monoxide and water vapor into the inner disc region.

Implications for Rocky Planet Formation

Beyond solving the mystery of CO-rich discs, these findings have profound implications for our understanding of how rocky planets acquire their chemical compositions. The presence of substantial quantities of carbon and oxygen in HD 131488's terrestrial planet zone, combined with a relative scarcity of hydrogen, suggests that any planets forming in this region would have high "metallicity"—a term astronomers use to describe the abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium.

This chemical composition would distinguish such planets from those that form in hydrogen-rich primordial nebulae, potentially leading to worlds with fundamentally different atmospheric and geological characteristics. The research provides observational evidence for theoretical models suggesting that the timing and location of planet formation within a protoplanetary disc can dramatically influence a planet's ultimate composition and habitability potential.

Key Discoveries from the JWST Observations

- First detection of UV-fluorescent CO: JWST captured the first-ever observation of ultraviolet-excited carbon monoxide molecules in a protoplanetary debris disc, opening a new window into studying these systems

- Thermal disequilibrium: The dramatic difference between vibrational (8,800K) and rotational (150-450K) temperatures reveals that the gas is not in thermal equilibrium, indicating active energy input from stellar radiation

- Exocometary origin confirmed: The gas properties strongly support the hypothesis that the CO is continuously replenished by vaporizing comets rather than being a primordial remnant

- Chemical enrichment: High carbon and oxygen content with depleted hydrogen suggests that terrestrial planets forming in this zone would have compositions distinct from gas giants

- Water vapor presence: Evidence for water vapor as a collisional partner indicates that cometary ices are being released into the inner disc environment

The Broader Context of Planetary System Evolution

This discovery fits into a larger framework of understanding how planetary systems evolve from their initial formation in protoplanetary discs to mature systems like our own solar system. The Spitzer Space Telescope and other infrared observatories had previously identified numerous debris discs around young stars, but JWST's superior sensitivity and spectral resolution allow astronomers to probe these systems in unprecedented detail.

The presence of cometary bodies in the inner regions of young stellar systems is not entirely surprising—our own solar system experienced a period of intense cometary bombardment early in its history, an epoch known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. However, directly observing this process occurring around other stars provides invaluable validation of our theoretical models and helps astronomers understand the diversity of planetary system architectures observed throughout our galaxy.

Research teams using various observatories have documented that planet-forming discs lose their gas content on relatively rapid timescales, typically within a few million years. The mechanism by which some discs maintain substantial gas reservoirs for longer periods has remained contentious. The JWST observations of HD 131488 demonstrate that at least some of these systems achieve this through continuous replenishment via cometary destruction—a dynamic, ongoing process rather than a static remnant.

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

While this study provides crucial insights into HD 131488 specifically, it also raises new questions and highlights the need for additional observations. How common are these CO-rich debris discs in the broader population of young stars? Do different stellar types exhibit different patterns of cometary activity? What factors determine whether a young planetary system will develop a robust population of comets capable of sustaining gas replenishment?

The research team's findings suggest that JWST observations of additional CO-rich systems could help answer these questions and build a more comprehensive picture of planetary system evolution. The telescope's ability to detect and characterize warm molecular gas in the inner regions of debris discs represents a unique capability that complements observations at other wavelengths, from radio observations with ALMA to optical and ultraviolet studies with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Furthermore, future observations might detect other molecular species beyond carbon monoxide and water vapor, providing additional constraints on the composition of the vaporizing comets and the chemical processes occurring in these extreme environments. The presence of organic molecules, for instance, would have fascinating implications for the delivery of prebiotic chemistry to nascent planetary surfaces.

A Testament to JWST's Revolutionary Capabilities

This discovery exemplifies exactly the type of groundbreaking science that JWST was designed to enable. Since its launch and subsequent deployment, the observatory has delivered a steady stream of first-time detections and unprecedented observations across multiple fields of astronomy, from the earliest galaxies in the universe to the atmospheric compositions of exoplanets and now to the intricate details of protoplanetary disc chemistry.

The telescope's infrared sensitivity and high-resolution spectroscopy capabilities allow it to probe wavelength regions and detect spectral features that were previously inaccessible or required prohibitively long observation times with earlier instruments. In the case of HD 131488, a single hour of observation yielded insights that fundamentally advance our understanding of planetary system formation—a testament to the observatory's transformative impact on astronomy.

As JWST continues its mission, astronomers anticipate many more discoveries that will challenge existing paradigms and reveal new aspects of cosmic phenomena. The study of protoplanetary discs and planetary formation represents just one of many research areas benefiting from this revolutionary facility, alongside investigations of exoplanet atmospheres, stellar evolution, galaxy formation, and the nature of dark matter and dark energy.

The detection of UV-fluorescent carbon monoxide around HD 131488 may represent a single data point, but it illuminates a crucial chapter in the story of how planetary systems—including potentially habitable worlds—emerge from the chaotic, violent environments surrounding young stars. As astronomers continue to study this and similar systems, we move closer to understanding our own cosmic origins and the diversity of planetary environments that populate our galaxy.