A groundbreaking decade-long astronomical investigation has revealed that galactic evolution is profoundly influenced by cosmic neighborhood dynamics, with galaxies in densely populated regions of the universe developing at significantly slower rates than their isolated counterparts. The Deep Extragalactic Visible Legacy Survey (DEVILS), a collaborative project between the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) and the University of Western Australia, has unveiled its inaugural data release, providing unprecedented insights into how cosmic environments shape the life cycles of galaxies across billions of years of universal history.

This comprehensive dataset, representing ten years of meticulous observations and analysis, encompasses morphological classifications, redshift measurements, photometric and spectroscopic data, alongside detailed information about galaxy group environments and dark matter halo characteristics for thousands of celestial objects. The research, published in the prestigious Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, marks a significant milestone in our understanding of how galaxies transform over cosmic timescales, focusing specifically on systems that existed between three and five billion years ago.

Associate Professor Luke Davies from the University of Western Australia node of ICRAR, who led this pioneering research, explains that DEVILS fills a critical gap in astronomical surveys by examining the fine-scale environmental contexts surrounding individual galaxies during a pivotal epoch in cosmic history. Unlike previous large-scale surveys that painted broad strokes of galactic evolution, DEVILS provides the granular detail necessary to understand how local cosmic conditions influence stellar birth rates, structural development, and the ultimate fate of galaxies.

The Cosmic Geography of Galaxy Evolution

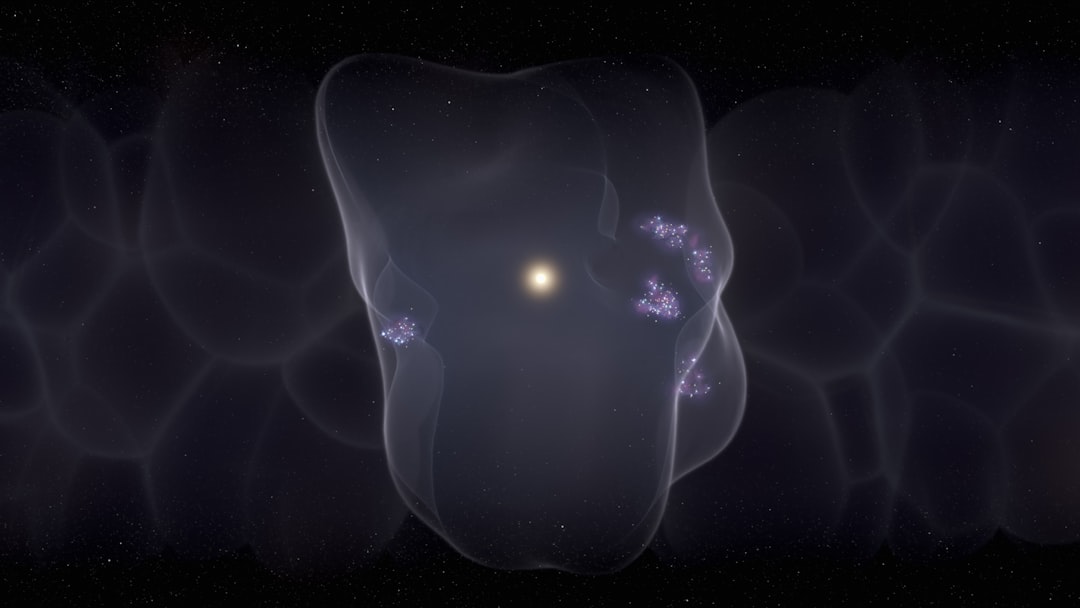

The DEVILS survey introduces a revolutionary approach to understanding galactic development by mapping what researchers call the "small-scale environment" of galaxies. This concept parallels terrestrial geography, where understanding whether a location sits in a valley, on a mountain, or across a plateau provides crucial context for its characteristics and development potential.

"While previous surveys during this period of universal history have explored the broad evolution of galaxy properties, they have inherently lacked the capacity to determine the finer details of the cosmic landscape. In the DEVILS survey, we have been able to zoom in and focus on mapping out the small-scale environment of galaxies – such as mountains, hills, valleys and plateaus as compared to large-scale environments such as oceans or continents," explained Professor Davies.

This geographic analogy proves particularly apt when examining how galaxy clusters, groups, and pairs create distinct evolutionary pathways. Just as human settlements develop differently in isolated rural areas versus dense urban centers, galaxies exhibit dramatically different growth patterns depending on their cosmic neighborhoods. The DEVILS data reveals that galaxies residing in what astronomers call "overdense regions" – the bustling metropolitan areas of the cosmos – experience stunted growth compared to their counterparts in more sparsely populated cosmic suburbs.

Understanding the Star Formation Suppression Mechanism

At the heart of this research lies a fundamental question in modern astrophysics: why do galaxies in crowded environments cease forming stars at higher rates than isolated systems? The answer involves complex physical processes that disrupt or remove the cold gas necessary for stellar birth. According to research from the Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories, several mechanisms work in concert to quench star formation in dense environments.

Galaxies broadly fall into two categories: blue, gas-rich, star-forming systems and red, gas-poor, quiescent systems with minimal ongoing stellar production. All galaxies begin their lives as low-mass, blue systems actively producing stars, gradually transitioning toward quiescence as they age and exhaust their fuel supplies. However, environmental factors dramatically accelerate this transition in crowded cosmic regions.

Physical Processes Driving Environmental Quenching

The DEVILS research identifies several key mechanisms responsible for suppressing star formation in dense galactic neighborhoods:

- Ram-pressure stripping: As galaxies move through the hot, diffuse gas pervading galaxy clusters at velocities reaching thousands of kilometers per second, they experience a "cosmic headwind" that strips away their cold gas reserves, much like wind removing leaves from trees. This process, extensively studied by the European Southern Observatory, can completely denude a galaxy of star-forming material within hundreds of millions of years.

- Tidal interactions: Gravitational forces from neighboring galaxies distort and disrupt the delicate structures within galaxies, heating gas and triggering temporary bursts of star formation that ultimately consume available fuel more rapidly than in isolated systems.

- Strangulation: Galaxy groups and clusters contain vast reservoirs of hot gas that prevent infalling galaxies from accreting fresh cold gas from the intergalactic medium, effectively starving them of the raw materials needed for continued star formation.

- Harassment: Repeated high-speed encounters between galaxies in dense environments create cumulative gravitational disturbances that gradually transform disk galaxies into more compact, spheroidal systems with reduced star formation capacity.

These mechanisms don't operate in isolation but work synergistically to transform the galactic population in overdense cosmic regions. The DEVILS data provides compelling statistical evidence for these processes, showing clear trends of decreasing star formation rates as local galaxy surface density increases.

Quantifying Environmental Impact Through Advanced Observations

The DEVILS team employed sophisticated observational techniques to map the relationship between galactic environments and evolutionary trajectories. Using spectroscopic data that measures the precise distances to thousands of galaxies through their redshifts – the stretching of light caused by cosmic expansion – researchers constructed three-dimensional maps of the universe as it appeared billions of years ago.

The survey's focus on galaxies at lookback times of three to five billion years proves particularly significant, as this epoch represents a crucial transition period in cosmic history. During this era, the universe had cooled sufficiently from the Big Bang for complex structures to form, yet remained young enough that many galaxies actively produced stars. By comparing these ancient systems to present-day galaxies observed in surveys like COSMOS 2020, astronomers can trace the complete evolutionary pathway from active star formation to quiescence.

The data release includes detailed morphological classifications for each galaxy, categorizing them based on structural features visible in high-resolution imaging from facilities like the Subaru Hyper Suprime-Cam. These classifications reveal that environmental density correlates not only with star formation rates but also with fundamental galactic architecture. Disk galaxies, characterized by flat, rotating structures rich in gas and young stars, predominate in low-density regions. Conversely, elliptical and spheroidal galaxies – compact, gas-poor systems dominated by old stellar populations – become increasingly common in high-density environments.

Dark Matter Halos and Group Dynamics

A particularly innovative aspect of the DEVILS survey involves mapping dark matter halos – the invisible gravitational scaffolding that anchors visible galaxies. Though dark matter itself remains undetectable through direct observation, its gravitational influence on visible matter reveals its distribution and mass. The DEVILS team used sophisticated algorithms to identify galaxy groups and estimate their total dark matter content, providing crucial context for understanding environmental effects.

Galaxies don't exist in isolation but reside within dark matter halos of varying masses. Small halos host individual galaxies, while massive halos contain entire galaxy clusters with hundreds or thousands of members. The DEVILS data shows that halo mass strongly predicts the star formation properties of resident galaxies, with more massive halos correlating with higher fractions of quiescent systems. This relationship suggests that the gravitational potential wells created by dark matter play a fundamental role in regulating gas flows and star formation across cosmic time.

The Nature Versus Nurture Debate in Galactic Evolution

Professor Davies draws a compelling parallel between galactic and human development, framing the research findings within a familiar "nature versus nurture" framework. Just as human personalities reflect both innate characteristics and environmental influences, galactic properties emerge from the interplay between intrinsic factors like initial mass and external environmental pressures.

"Our upbringing and environment influence who we are. Someone who has lived their whole life in the city may have a very different personality compared to someone who lives remotely or in an isolated community. Galaxies are no different," Davies noted, emphasizing the profound impact of cosmic neighborhoods on galactic destinies.

This analogy extends beyond simple metaphor to capture genuine physical parallels. Urban environments provide abundant social interactions but also impose constraints – noise, pollution, limited space – that shape development. Similarly, dense galactic environments offer frequent interactions that can trigger merger-driven growth but simultaneously strip away the resources needed for sustained star formation. Isolated galaxies, like rural residents, develop more independently, maintaining their gas supplies and forming stars at steady rates determined primarily by internal processes rather than external interference.

The DEVILS data quantifies these environmental effects with unprecedented precision, revealing that galaxies in the densest environments form stars at rates significantly lower than their isolated counterparts of similar mass. This suppression manifests across all morphological types, though disk galaxies show particularly dramatic effects as their extended gas reservoirs prove vulnerable to stripping and heating.

Implications for Cosmic Structure Formation

The DEVILS findings carry profound implications for understanding large-scale structure formation in the universe. According to the standard cosmological model, matter in the early universe existed in a nearly uniform distribution with tiny density fluctuations. Over billions of years, gravity amplified these fluctuations, pulling matter together into the intricate cosmic web of galaxy clusters, filaments, and voids we observe today.

As structures grew hierarchically – small systems merging to form progressively larger ones – galaxies found themselves in increasingly complex environments. The DEVILS research demonstrates that this environmental evolution fundamentally altered galactic populations, transforming actively star-forming systems into the massive elliptical galaxies that dominate present-day clusters. Understanding this transformation process proves essential for explaining why the universe looks the way it does today, with distinct galactic populations occupying different cosmic neighborhoods.

The research also connects to ongoing debates about galaxy formation efficiency. Theoretical models predict that only a small fraction of available baryonic matter (the ordinary matter making up stars, gas, and planets) actually forms stars within galaxies. Much of this matter remains in diffuse intergalactic gas or gets expelled from galaxies through energetic processes like supernova explosions and active galactic nuclei. Environmental effects add another layer to this inefficiency, removing gas from galaxies before it can collapse into stars and thereby reducing the overall stellar content of the universe.

Future Directions and the WAVES Initiative

The DEVILS data release represents just the beginning of a broader research program aimed at comprehensively mapping galactic evolution across cosmic time. Professor Davies and his team have already begun planning the Wide Area VISTA Extragalactic Survey (WAVES), scheduled to commence data collection next year. WAVES will dramatically expand the scope of environmental studies by observing significantly larger cosmic volumes and including galaxies across a wider range of distances and environments.

By combining DEVILS' detailed environmental characterization with WAVES' statistical power, astronomers will construct an increasingly complete picture of how galaxies transform throughout universal history. This multi-survey approach mirrors successful strategies employed by other major astronomical programs, such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which revolutionized our understanding of cosmic structure through systematic observations of millions of galaxies.

The DEVILS dataset will also serve as a valuable resource for researchers worldwide, providing carefully calibrated measurements and environmental classifications that can be combined with data from other facilities. Space-based observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope offer complementary capabilities, probing even more distant galaxies and observing in infrared wavelengths that reveal star formation hidden by dust. By integrating DEVILS data with these multi-wavelength observations, astronomers can develop increasingly sophisticated models of galactic evolution that account for the full complexity of environmental influences.

Broader Scientific Context and Significance

The DEVILS research addresses fundamental questions that have motivated astronomical research for decades: How do galaxies form and evolve? What determines whether a galaxy continues forming stars or becomes quiescent? Why do different galactic populations occupy distinct cosmic environments? These questions connect to the broader goal of understanding cosmic evolution from the Big Bang to the present day, tracing how simple initial conditions gave rise to the rich diversity of structures we observe today.

Environmental studies like DEVILS also inform our understanding of galaxy formation physics at the most fundamental level. By observing how external factors influence star formation, gas content, and morphology, astronomers can test theoretical models of the physical processes governing galactic behavior. These models, refined through comparison with observational data, ultimately help explain not just how galaxies evolve but why the laws of physics produce the particular cosmic architecture we inhabit.

As astronomical surveys continue expanding in scope and sensitivity, the detailed environmental context provided by projects like DEVILS becomes increasingly valuable. Future facilities will observe galaxies at even greater distances, probing cosmic epochs when the first galaxies formed and environmental effects may have operated differently. Understanding present-day environmental influences provides the foundation for interpreting these distant observations and reconstructing the complete history of galactic evolution across the entire age of the universe.

The DEVILS first data release thus represents a significant milestone in humanity's quest to understand our cosmic origins and the processes that shaped the universe we observe today. Through patient observation, careful analysis, and innovative techniques for mapping galactic environments, astronomers continue revealing the intricate relationships between galaxies and their cosmic neighborhoods, demonstrating that in the cosmos as on Earth, location matters profoundly for determining developmental trajectories and ultimate destinies.