In a groundbreaking discovery that reshapes our understanding of planetary formation, astronomers have uncovered compelling evidence explaining why the galaxy's most abundant type of planet forms in such unexpected proximity to their host stars. The research, focusing on the remarkably young stellar system V1298 Tau, reveals that the ubiquitous super-Earths and sub-Neptunes orbiting close to distant suns may begin their lives as bloated gas giants before being sculpted down to smaller, denser worlds by intense stellar radiation. This finding, published in Nature journal, provides the missing piece in a cosmic puzzle that has perplexed astronomers since the dawn of exoplanet discovery.

Our own solar system presents an anomaly in the galactic neighborhood. Mercury, our innermost planet, is remarkably small—even smaller than some of the massive moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn. This configuration stands in stark contrast to what astronomers have discovered across the Milky Way, where the vast majority of planetary systems host substantial worlds—typically ranging between Earth and Neptune in size—orbiting far closer to their stars than Mercury does to our Sun. Understanding why our cosmic backyard differs so dramatically from the galactic norm has become one of astronomy's most pressing questions.

The Exoplanet Revolution and the Super-Earth Mystery

When the exoplanet revolution began in the 1990s, astronomers initially suspected that the prevalence of large, close-orbiting planets was merely an artifact of observational limitations. The transit method, which detects planets by measuring the slight dimming of starlight as a world passes in front of its host star, naturally favors the detection of larger planets with shorter orbital periods. These "hot Jupiters" and massive worlds were simply easier to spot—they blocked more light and transited more frequently, making them low-hanging fruit for early planet hunters.

However, as detection methods improved and missions like Kepler and TESS catalogued thousands of exoplanets, a remarkable pattern emerged. The observational bias theory crumbled under the weight of statistical evidence. Hot super-Earths—worlds with masses between 1.5 and 10 times that of Earth orbiting within the orbit of Mercury—weren't just easy to find; they were genuinely the most common planetary configuration in our galaxy. According to data from the NASA Exoplanet Archive, these intermediate-mass worlds appear around 30-50% of Sun-like stars, making them far more prevalent than gas giants like Jupiter or small rocky worlds like Earth.

Competing Theories: Migration Versus In-Situ Formation

The prevalence of close-orbiting super-Earths sparked intense theoretical debate within the astronomical community, crystallizing into two primary competing hypotheses. The first theory proposed planetary migration—the idea that these worlds formed farther from their stars in cooler, gas-rich regions of protoplanetary disks before gradually spiraling inward. This concept gained credibility from computer simulations of our own solar system's early history, which suggest that gravitational interactions between Jupiter and Saturn triggered a dramatic cosmic reshuffling known as the Nice Model.

In this scenario, the giant planets engaged in a gravitational dance that sent them careening to new orbital positions. While this pushed the gas giants outward in our system, similar interactions in other stellar systems could theoretically drive planets inward, parking them in tight orbits close to their host stars. The migration hypothesis offered an elegant explanation: super-Earths might be former giants that lost their way home.

The alternative theory suggested in-situ formation—that these planets formed right where we find them today, close to their stars. This new research adds a crucial refinement to this hypothesis, proposing that hot super-Earths don't start out as the modest-sized worlds we observe today, but rather as significantly larger, puffier planets that undergo dramatic transformation over millions of years.

A Cosmic Laboratory: The V1298 Tau System

The breakthrough came from detailed observations of V1298 Tau, a stellar infant barely 20 million years old—a cosmic newborn by astronomical standards, considering our Sun has existed for 4.6 billion years. Despite its youth, this star already hosts four substantial planets, all orbiting closer than Mercury's distance from our Sun. Initial transit observations revealed these worlds to be giants, with diameters ranging from 5 to 10 times Earth's diameter, placing them in the size category spanning from Neptune to Jupiter.

For years, astronomers knew the sizes of these planets but remained frustrated by a critical gap in their knowledge: their masses. Without mass measurements, scientists couldn't determine whether these were dense, rocky super-Earths, gas-rich mini-Neptunes, or something entirely different. The density of a planet—calculated from its mass and volume—tells us about its composition and structure, providing crucial insights into its formation history and evolutionary trajectory.

Revolutionary Measurement Technique: Transit Timing Variations

The research team, led by Dr. John H. Livingston and published in their study "A young progenitor for the most common planetary systems in the Galaxy," employed an ingenious technique called transit timing variation (TTV) analysis to crack this problem. In a single-planet system, transits would occur with metronomic precision, following perfect Keplerian orbits dictated by the star's gravity alone. However, in multi-planet systems, the gravitational influences between planets create subtle perturbations in their orbits.

These gravitational tugs cause planets to speed up or slow down slightly in their orbits, creating minute variations in when transits occur—sometimes arriving a few minutes early, sometimes a few minutes late. By meticulously tracking these timing variations over multiple transits and constructing sophisticated computer models of the gravitational interactions, the team successfully calculated the masses of all four worlds. Their measurements revealed masses ranging from 5 to 15 Earth masses, firmly placing these planets in the super-Earth to sub-Neptune category.

"What we've discovered is essentially a snapshot of planetary evolution in action—we're witnessing the progenitors of the galaxy's most common planetary systems before they've been sculpted into their final forms by stellar radiation," explains the research team in their Nature publication.

The Super-Puff Revelation

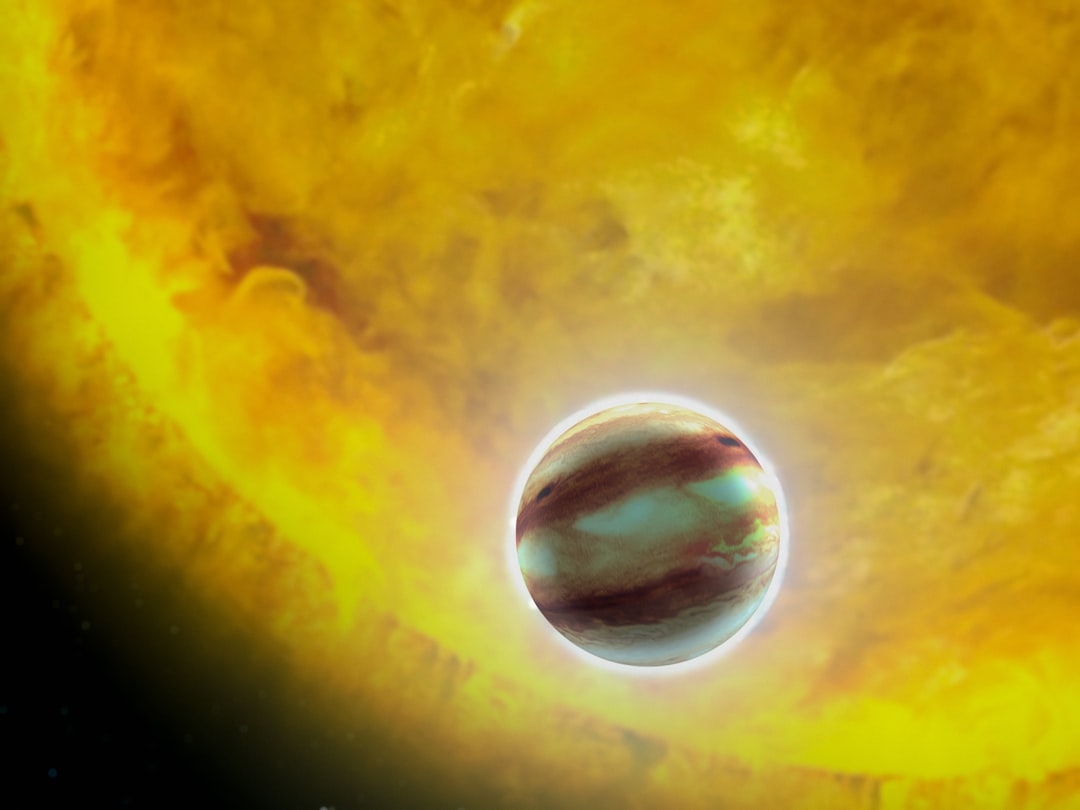

When the team combined their mass measurements with the previously known sizes, they calculated the densities of these young planets and made a startling discovery: all four worlds possess extraordinarily low densities, less than that of packing foam or Styrofoam. These are "super-puff" planets—worlds with enormous, bloated atmospheres of hydrogen and helium that extend far into space, giving them sizes disproportionate to their actual mass.

To put this in perspective, these planets have densities ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 grams per cubic centimeter—comparable to cotton candy. For comparison, Earth has a density of 5.5 g/cm³, while even the gas giant Saturn, the least dense planet in our solar system, has a density of 0.687 g/cm³. The V1298 Tau planets are cosmic balloons, their small rocky or icy cores surrounded by vast, tenuous envelopes of primordial gas.

Stellar Sculpting: From Puff to Planet

This discovery illuminates the evolutionary pathway that transforms these bloated gas worlds into the compact super-Earths observed around mature stars. Young stars like V1298 Tau are notoriously violent, unleashing intense stellar flares and powerful stellar winds that bombard nearby planets with high-energy radiation and streams of charged particles. This stellar onslaught acts like a cosmic sandblaster, gradually stripping away the extended hydrogen and helium atmospheres of close-orbiting planets.

The research team's models predict that over the next several hundred million years, the V1298 Tau planets will lose the vast majority of their atmospheric mass through a process called photoevaporation. Ultraviolet radiation from the star heats the upper atmosphere to extreme temperatures, giving gas molecules enough energy to escape the planet's gravity entirely. According to research from the European Space Agency's CHEOPS mission, this atmospheric erosion can remove hundreds of Earth masses of gas over cosmic timescales.

By the time the V1298 Tau system reaches an age comparable to our solar system, the team estimates these planets will have been whittled down to masses and densities closely matching the hot super-Earths and sub-Neptunes that populate mature planetary systems throughout the galaxy. The cosmic balloons will deflate, leaving behind denser cores that may retain thin secondary atmospheres composed of heavier elements released from the planet's interior.

Key Implications and Future Directions

This research resolves several long-standing puzzles in planetary science and opens new avenues for investigation:

- Formation Timeline: Super-Earths and sub-Neptunes form early in a star system's history as gas-rich worlds, not as bare rocky planets that later accrete atmospheres. This suggests that gas giant formation happens rapidly, within the first few million years of a star's life, before the protoplanetary disk dissipates.

- The Radius Valley: Observations have revealed a curious gap in the size distribution of exoplanets around 1.5-2 Earth radii, with fewer planets found in this range than expected. This "radius valley" can now be explained as the dividing line between worlds that retained enough atmosphere to remain sub-Neptunes and those that lost so much gas they became rocky super-Earths.

- Atmospheric Evolution: The findings provide crucial constraints for models of atmospheric escape and planetary evolution. Understanding how efficiently stellar radiation strips atmospheres helps predict which planets might retain habitable conditions over billions of years.

- Solar System Context: Our solar system's lack of close-orbiting super-Earths may result from Jupiter's early formation and subsequent migration, which could have cleared out material from the inner solar system or prevented planets from forming there in the first place. We may be living in an atypical system precisely because of Jupiter's gravitational dominance.

The Road Ahead: Next-Generation Observations

This discovery opens exciting opportunities for future observations with cutting-edge facilities. The James Webb Space Telescope can now target young planetary systems like V1298 Tau to study the composition of super-puff atmospheres in unprecedented detail, revealing the chemical fingerprints of primordial gas and tracking atmospheric loss in real-time. Upcoming missions like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will survey thousands of young stars, potentially finding more systems caught in this transitional phase.

Ground-based observatories equipped with adaptive optics and next-generation spectrographs will measure precise masses for even more young planets, building a comprehensive picture of how planetary systems evolve from birth to maturity. Each new discovery refines our understanding of the cosmic processes that shape worlds and helps answer the fundamental question: How common are planetary systems like our own?

The V1298 Tau system serves as a cosmic time machine, allowing us to witness the transformation that most planetary systems undergo—a violent, dramatic reshaping by stellar forces that determines the final architecture of mature planetary systems. In solving the mystery of super-Earth formation, astronomers have revealed that the galaxy's most common planets are not born fully formed but are sculpted over hundreds of millions of years by the relentless energy of their host stars. What we observe around mature stars are the survivors—planets that endured their star's tempestuous youth and emerged as the compact, dense worlds that dominate the galactic census of planets.