A groundbreaking computational study has unveiled the fundamental mechanisms driving the powerful jet streams that race across the atmospheres of our solar system's giant planets at speeds exceeding 2,000 kilometers per hour. Published in Science Advances, this research resolves a long-standing mystery in planetary science: why do the equatorial jet streams on Jupiter and Saturn flow eastward, while those on Uranus and Neptune surge westward? The answer, researchers have discovered, lies not in the planets' distance from the Sun or their individual characteristics, but in a single, elegant factor—atmospheric depth.

Led by Dr. Keren Duer, a guest researcher at Leiden University, an international team of scientists employed sophisticated computer simulations to model the atmospheric dynamics of all four giant planets in our solar system. Their findings reveal that rotating convection cells at the equators—massive circulation patterns that transport heat vertically through the atmosphere—play the decisive role in determining jet stream direction. This discovery not only enhances our understanding of planetary atmospheres within our own cosmic neighborhood but also provides crucial insights into the atmospheric behavior of thousands of exoplanets discovered orbiting distant stars throughout the Milky Way galaxy.

The Challenge of Understanding Giant Planet Atmospheres

For decades, planetary scientists have been captivated by the extreme weather systems that dominate the atmospheres of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. These gas and ice giants exhibit some of the most violent and persistent atmospheric phenomena in the solar system, with wind speeds that dwarf anything experienced on Earth. Jupiter's Great Red Spot, a storm system larger than our entire planet that has raged for centuries, represents just one example of the extraordinary atmospheric dynamics at play on these massive worlds.

The equatorial jet streams on these planets have proven particularly puzzling. Observations from spacecraft missions—including NASA's Voyager probes, the Galileo orbiter, and the Cassini-Huygens mission—have documented jet stream velocities ranging from 500 to 2,000 kilometers per hour (310 to 1,305 miles per hour). To put this in perspective, the fastest jet stream winds on Earth rarely exceed 400 kilometers per hour, making these planetary wind systems five times more powerful than anything in our own atmosphere.

The directional dichotomy between the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) and ice giants (Uranus and Neptune) has spawned numerous hypotheses over the years. Some researchers proposed that the difference stemmed from solar heating variations, with Uranus and Neptune receiving significantly less sunlight due to their greater distance from the Sun. Others suggested that each planet's unique internal heat sources, composition, or rotation rates might independently determine jet stream behavior. However, none of these explanations could satisfactorily account for all observed phenomena across all four planets.

Revolutionary Computer Modeling Reveals Universal Mechanism

The research team's breakthrough came through the development of advanced three-dimensional computer models that could simulate the complex fluid dynamics occurring within giant planet atmospheres. Unlike previous studies that often focused on individual planets or simplified two-dimensional models, this research employed comprehensive simulations that accounted for multiple variables simultaneously, including atmospheric composition, internal heat flow, planetary rotation rates, and the depth of the atmospheric layer.

The models revealed that atmospheric depth—the vertical extent of the gaseous envelope surrounding these planets—serves as the critical parameter determining jet stream direction. On Jupiter and Saturn, where the atmospheric layer is relatively shallow compared to the planets' overall radius, rotating convection cells at the equator create conditions that drive eastward jet streams. Conversely, on Uranus and Neptune, where the atmospheric layers extend deeper into the planetary interiors, the same convective processes generate westward-flowing jets.

"Understanding these flows is crucial because it helps us grasp the fundamental processes that govern planetary atmospheres—not only in our solar system but throughout the Milky Way. This discovery gives us a new tool to understand the diversity of planetary atmospheres and climates across the universe," explained Dr. Keren Duer, the study's lead author.

The convection cells themselves are enormous rotating structures that transfer thermal energy between the deep interior of the planet and the upper atmosphere. Similar to the convection currents that drive Earth's weather systems, but on a vastly larger scale, these cells create organized patterns of rising warm gas and sinking cool gas. The rotation of the planet interacts with these convection patterns through the Coriolis effect, deflecting the flow and generating the powerful jet streams observed at the equator.

Implications for Exoplanetary Science

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this research lies in its applicability to exoplanetary atmospheres. Over the past two decades, astronomers have discovered thousands of planets orbiting other stars, many of which are gas giants similar to or even larger than Jupiter. Advanced space telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope, have enabled scientists to detect and characterize jet streams on several of these distant worlds.

The study highlights several exoplanets where jet stream activity has been observed and documented:

- HD 209458 b (159 light-years distant): One of the first exoplanets where atmospheric circulation was detected, exhibiting extreme wind speeds

- HD 189733 b (64.5 light-years): A hot Jupiter with documented jet stream velocities and distinctive blue coloration from silicate particles in its atmosphere

- WASP-43 b (284 light-years): Features rapidly varying atmospheric conditions and powerful equatorial winds

- WASP-18 b (380 light-years): An ultra-hot Jupiter with extreme temperatures and violent atmospheric dynamics

- HAT-P-7 b (1,040 light-years): Displays evidence of changing wind patterns and possible mineral clouds

- WASP-76 b (634 light-years): Famous for its extreme conditions where iron vaporizes and potentially rains down on the night side

- WASP-121 b (850 light-years): An ultra-hot Jupiter with atmospheric temperatures exceeding 2,500 degrees Celsius

- GJ 1214 b (48 light-years): A smaller super-Earth or mini-Neptune with a radius approximately 2.7 times that of Earth

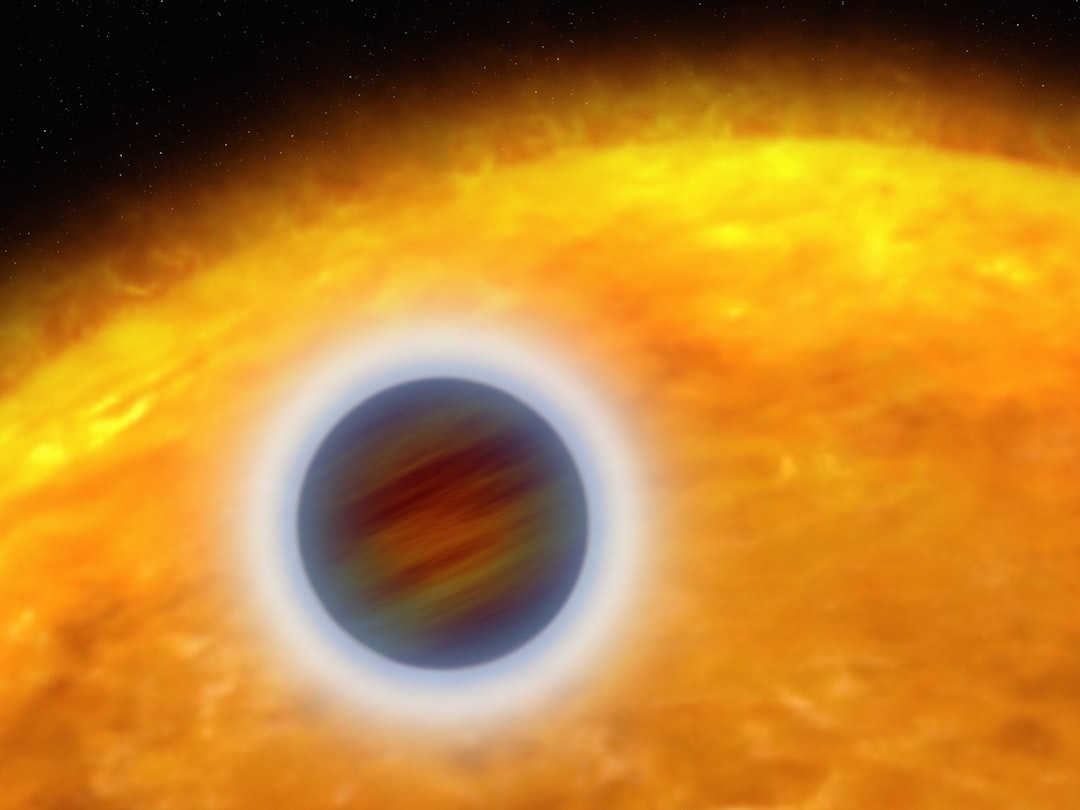

Most of these exoplanets fall into the category of "Hot Jupiters" or "Ultra-Hot Jupiters"—gas giants that orbit extremely close to their parent stars, completing full orbits in less than one day to just over 4.5 days. By comparison, Jupiter requires 11.86 Earth years to complete one orbit, Saturn takes 29.46 years, Uranus needs 84 years, and Neptune requires 164.8 years. This proximity to their stars subjects Hot Jupiters to intense stellar radiation, heating their atmospheres to extreme temperatures and driving jet stream velocities that can exceed 3,600 kilometers per hour (2,237 miles per hour)—nearly twice as fast as the most powerful winds in our solar system.

Exotic Atmospheric Phenomena on Distant Worlds

The extreme conditions on these exoplanets create atmospheric phenomena unlike anything observed in our solar system. Some Hot Jupiters exhibit persistent "hotspots"—regions of exceptionally high temperature that remain fixed relative to the planet's rotation. Others display dramatically different jet stream patterns on their day sides compared to their night sides, creating complex three-dimensional wind patterns that challenge our understanding of atmospheric dynamics.

Perhaps most remarkably, some ultra-hot Jupiters have atmospheres containing vaporized heavy metals including iron, titanium, and even liquid rock droplets. On WASP-76 b, for instance, temperatures on the day side reach approximately 2,400 degrees Celsius—hot enough to vaporize iron. The planet's powerful jet streams transport this vaporized iron to the cooler night side, where it condenses and potentially falls as metallic rain. Such exotic conditions push the boundaries of atmospheric science and require new theoretical frameworks to understand.

Advancing Planetary Formation and Evolution Theory

Beyond explaining current atmospheric dynamics, this research provides valuable insights into planetary formation and evolution processes. The atmospheric depth that determines jet stream direction is itself a product of the planet's formation history, internal structure, and long-term evolution. Gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn are thought to have formed through core accretion—a process where a solid core first accumulates, then gravitationally captures a massive gaseous envelope from the protoplanetary disk.

The ice giants Uranus and Neptune, despite their larger atmospheric depths relative to their size, contain proportionally more heavy elements and ices compared to Jupiter and Saturn. This compositional difference reflects their formation in the outer regions of the solar nebula, where temperatures were cold enough for volatile compounds like water, methane, and ammonia to condense into solid ice. Understanding how these compositional and structural differences manifest in observable atmospheric phenomena like jet streams provides crucial constraints for planetary formation models.

For exoplanets, this connection between internal structure and atmospheric behavior offers a powerful diagnostic tool. By observing jet stream directions and velocities on distant worlds, astronomers can infer properties of the planetary interior that would otherwise remain inaccessible. This capability becomes particularly valuable for characterizing the diverse population of giant exoplanets, which exhibit a wide range of sizes, compositions, and orbital configurations that challenge simple classification schemes based solely on our solar system's architecture.

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The success of this modeling approach opens numerous avenues for future research. Scientists can now apply these techniques to investigate other aspects of giant planet meteorology, including the formation and persistence of large storm systems, the vertical structure of atmospheric layers, and the interaction between atmospheric dynamics and magnetic fields. The models can also be refined to incorporate additional physical processes, such as photochemical reactions driven by stellar ultraviolet radiation, the effects of atmospheric metallicity on heat transport, and the role of cloud formation in modulating atmospheric circulation.

Upcoming observational facilities will provide unprecedented opportunities to test and refine these models. The James Webb Space Telescope, with its powerful infrared capabilities, can detect temperature variations and chemical signatures in exoplanetary atmospheres with remarkable precision. Future missions, including the proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory and European Space Agency's ARIEL (Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey), will systematically characterize the atmospheres of hundreds of exoplanets, providing a statistical sample that can reveal universal patterns in planetary atmospheric behavior.

Within our own solar system, continued monitoring by ground-based telescopes and future spacecraft missions will track how jet streams evolve over time in response to seasonal changes and long-term climate variations. The upcoming Europa Clipper and JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) missions will provide new observations of Jupiter's atmosphere, while proposed missions to the ice giants could revolutionize our understanding of Uranus and Neptune.

A Unified Framework for Planetary Atmospheres

Perhaps the most profound implication of this research is its demonstration that universal physical principles can explain the diverse atmospheric behaviors observed across vastly different planetary environments. Rather than requiring separate, planet-specific explanations for each observed phenomenon, scientists can now apply a unified framework based on fundamental fluid dynamics and thermodynamics.

This unification represents a major advance in planetary science, comparable to how Newton's laws of motion unified terrestrial and celestial mechanics, or how plate tectonics provided a single framework for understanding Earth's geological diversity. By identifying atmospheric depth as the key parameter controlling jet stream direction, researchers have reduced the complexity of giant planet atmospheres to a more manageable and predictable system.

As our catalog of known exoplanets continues to grow—currently exceeding 5,000 confirmed worlds with thousands more candidates awaiting verification—the need for such unifying principles becomes increasingly important. Rather than studying each planet as a unique case, scientists can now categorize and predict atmospheric behaviors based on fundamental physical properties that can be determined through observation or inferred from formation models.

The journey to understand planetary atmospheres continues, with each discovery building upon previous insights and raising new questions to investigate. As Dr. Duer's research demonstrates, sometimes the most elegant explanations are also the most powerful, revealing unexpected connections between seemingly disparate phenomena. What other atmospheric mysteries await resolution through careful modeling and observation? How will these insights inform our search for potentially habitable worlds among the thousands of exoplanets yet to be discovered? Only continued scientific investigation will reveal the answers, reminding us why the pursuit of knowledge about our cosmic environment remains one of humanity's most compelling endeavors.