In the vast cosmic hierarchy of black holes, there exists a puzzling gap that has long troubled astronomers. While we've confirmed the existence of stellar-mass black holes formed from collapsing stars and supermassive black holes lurking at the centers of galaxies, a mysterious middle ground remains largely uncharted. These elusive objects, known as intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs), should theoretically bridge the gap between their smaller and larger cousins, yet definitive proof of their existence has remained frustratingly out of reach—until now, when the most powerful space telescope ever built has turned its infrared gaze toward one of the most promising candidates in our cosmic neighborhood.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has recently completed observations of Omega Centauri, a spectacular globular cluster that may harbor one of these missing-link black holes. With masses ranging from approximately 100 to 100,000 solar masses, IMBHs occupy a critical evolutionary stage in our understanding of how supermassive black holes grew to their current enormous sizes in the early universe. The search for these objects represents one of the most significant challenges in modern astrophysics, with implications that extend far beyond simple cosmic bookkeeping.

The Enigmatic Nature of Omega Centauri

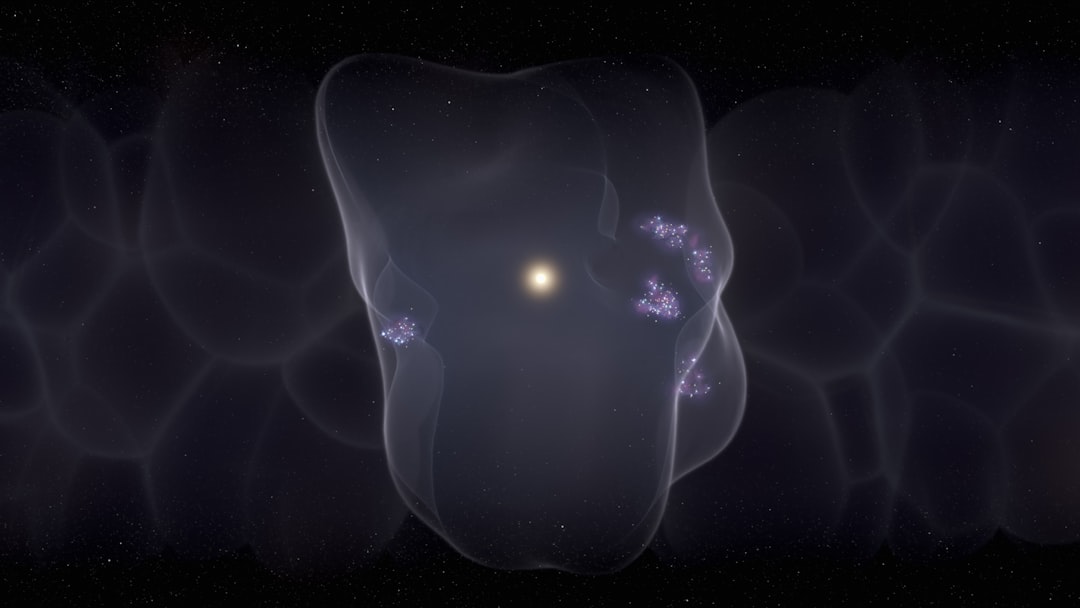

Located approximately 17,000 light-years from Earth, Omega Centauri stands as one of the most magnificent objects visible in the southern sky. Known to ancient astronomers who mistook it for a single brilliant star, this globular cluster actually contains roughly 10 million stars packed into a spherical region spanning about 150 light-years across. Modern astronomical research suggests that Omega Centauri isn't simply a typical globular cluster—it may represent the stripped core of a galaxy" class="glossary-term-link" title="Learn more about Dwarf Galaxy">dwarf galaxy that was gravitationally disrupted and cannibalized by our Milky Way billions of years ago.

This unusual origin story makes Omega Centauri an ideal location to search for an IMBH. If it once was the center of a small galaxy, it should have retained the central black hole that likely anchored that galaxy's structure. The Hubble Space Telescope has provided compelling evidence supporting this hypothesis through decades of meticulous observations, but the JWST's unprecedented infrared capabilities offer new opportunities to probe the cluster's dense core with extraordinary precision.

Velocity Signatures: Stars Moving Too Fast to Escape

Black holes, by their very nature, cannot be directly observed—they emit no light and remain invisible against the cosmic backdrop. However, their presence can be inferred through the gravitational influence they exert on surrounding matter. Just as we confirmed the existence of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, by tracking the orbital motions of nearby stars, astronomers are employing similar techniques to hunt for an IMBH in Omega Centauri.

In a groundbreaking 2024 study, researchers analyzed more than 500 Hubble images spanning two decades to measure the velocities of 1.4 million individual stars within the cluster. This painstaking work revealed seven stars in the cluster's central region moving at velocities exceeding the escape velocity—the speed required to break free from the cluster's gravitational pull. Yet remarkably, these stars remain bound to Omega Centauri, suggesting the presence of an additional massive object providing the gravitational anchor necessary to retain them.

"The discovery of fast-moving stars that should have escaped but remain gravitationally bound provides some of the most compelling indirect evidence for an intermediate-mass black hole," explains the research team. "These velocity measurements allow us to constrain the mass of the invisible object holding these stars in their orbits."

Constraints from Previous Observations

Based on the dynamics of these fast-moving stars, previous research established a plausible mass range for the putative IMBH of between 39,000 and 47,000 solar masses, with an extreme lower limit of 8,200 solar masses. These estimates rely on sophisticated gravitational modeling and assume that the observed stellar velocities result from a single massive compact object rather than a distributed mass of stellar remnants or other exotic configurations.

JWST's Infrared Investigation: Searching for Accretion Signatures

The new research, led by Steven Chen from The George Washington University and submitted to The Astrophysical Journal, takes a different approach to the IMBH puzzle. Rather than focusing solely on stellar dynamics, Chen's team utilized JWST observations to search for electromagnetic emissions from accretion—the process by which black holes consume surrounding matter and release energy in the form of radiation.

The JWST observed Omega Centauri in 2024 using both its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) and Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam), providing unprecedented views of the cluster's crowded central region. These observations aimed to detect any infrared signatures that might indicate active accretion onto an IMBH. According to established models of black hole accretion physics, even modest rates of matter consumption should produce detectable emissions across multiple wavelengths.

The Challenge of Extreme Stellar Crowding

Attempting to identify a single point source of emission in Omega Centauri's core presents extraordinary technical challenges. The central region contains an estimated tens of thousands of stars per cubic light-year—a density almost unimaginable compared to our Sun's relatively isolated neighborhood. At a distance of 17,000 light-years, even JWST's remarkable resolution cannot always distinguish individual stars from their neighbors, and what appears as a single bright point could actually represent multiple overlapping stellar sources.

The research team carefully analyzed the JWST data, focusing on the seven previously identified fast-moving stars and their immediate surroundings. They searched for any excess infrared emission that couldn't be attributed to normal stellar sources, which might indicate the presence of hot gas spiraling into a black hole's accretion disk.

New Mass Constraints and Accretion Models

While the JWST observations couldn't provide definitive confirmation of an IMBH's presence, they succeeded in placing tighter constraints on its properties. The research excluded the previously suggested lower mass limit of 8,200 solar masses and instead suggests a mass of approximately 20,000 solar masses—significantly smaller than earlier dynamical estimates but still firmly in the intermediate-mass range.

These constraints depend critically on assumptions about accretion efficiency—how effectively the black hole converts infalling matter into observable radiation. The lack of strong infrared emission in the JWST data indicates that if an IMBH exists in Omega Centauri, it must be accreting matter at an extremely low rate, operating in what astronomers call a "quiescent" or "low-luminosity" state.

Key Findings from the JWST Analysis

- No Isolated Point Source: The observations found no evidence for a single, isolated infrared source that could be definitively identified as an accreting IMBH in the region of interest

- Revised Mass Estimates: Based on emission limits and accretion models, the data suggests an IMBH mass around 20,000 solar masses, lower than some previous dynamical estimates

- Low Accretion Rate: The absence of strong infrared signatures indicates the black hole, if present, is consuming matter at a remarkably slow rate compared to actively feeding black holes

- Environmental Challenges: The extreme stellar crowding in Omega Centauri's core significantly complicates efforts to identify faint emission from a quiescent black hole

Implications for Black Hole Evolution Theory

The search for IMBHs extends beyond simple cosmic census-taking—these objects may hold crucial clues to one of astronomy's most pressing questions: How did supermassive black holes grow to millions or billions of solar masses so quickly in the early universe? Observations from JWST and other telescopes have revealed fully-formed supermassive black holes existing when the universe was less than a billion years old, leaving insufficient time for them to grow from stellar-mass seeds through normal accretion processes.

IMBHs could represent an intermediate evolutionary stage, formed through the merger of multiple stellar-mass black holes in dense stellar environments like globular clusters. Alternatively, they might form directly from the collapse of massive gas clouds in the early universe, providing the "heavy seeds" necessary to explain the rapid growth of supermassive black holes. Understanding whether IMBHs exist and how they form addresses fundamental questions about black hole formation and evolution across cosmic history.

Future Observations and the Path Forward

The research team emphasizes that JWST's contributions to the IMBH search are far from complete. Future observations will combine JWST's deep infrared imaging with Hubble's extensive historical dataset to refine proper motion measurements—the apparent motion of stars across the sky over time. These combined observations should reveal additional fast-moving stars too faint for previous detection, potentially strengthening the dynamical case for an IMBH.

Moreover, the emission limits established by this research provide valuable constraints for theoretical models of black hole accretion in low-rate regimes. If future observations definitively confirm an IMBH's presence through improved stellar dynamics measurements, the lack of strong electromagnetic emission will require refinement of our understanding of how black holes behave when starved of matter.

"Despite the unprecedented depth and resolution that JWST offers, searching for IMBH signals in very crowded environments remains challenging," the authors acknowledge. "Nevertheless, future JWST observations can further improve our understanding by uncovering fainter stars and placing ever-tighter constraints on emission from any central massive object."

The Process of Scientific Elimination

The quest to confirm IMBHs may not culminate in a single dramatic "Eureka!" moment. Instead, as this research demonstrates, the path forward likely involves a gradual process of elimination—systematically ruling out alternative explanations until the presence of an intermediate-mass black hole becomes the only viable conclusion. Each new observation, whether from JWST, Hubble, or future facilities, adds another piece to this cosmic puzzle.

Other potential IMBH candidates exist throughout the universe, including in the centers of dwarf galaxies, ultra-luminous X-ray sources, and other globular clusters. The techniques being refined through the study of Omega Centauri will prove invaluable for investigating these other candidates, potentially revealing a population of missing-link black holes that has eluded detection for decades.

The Broader Context of Black Hole Research

The search for intermediate-mass black holes represents just one frontier in the rapidly evolving field of black hole astrophysics. Recent years have witnessed revolutionary advances, from the first direct image of a black hole's shadow by the Event Horizon Telescope to the detection of gravitational waves from merging black holes by LIGO and Virgo observatories. Each discovery adds to our understanding of these extreme objects and their role in shaping cosmic structure.

As JWST continues its mission and next-generation observatories come online, including the Extremely Large Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, our ability to probe the universe's most enigmatic objects will only improve. The intermediate-mass black holes that have remained hidden for so long may finally reveal themselves, completing our picture of black hole populations across the cosmic mass spectrum and illuminating the processes that govern the growth of the universe's most massive objects.

For now, Omega Centauri remains the most promising laboratory for IMBH studies, its dense stellar core harboring secrets that may fundamentally reshape our understanding of black hole evolution and galaxy formation throughout cosmic history.