In the vast cosmic tapestry of our galaxy, red dwarf stars reign supreme in numbers, comprising roughly 75% of all stellar objects in the Milky Way. These dim, long-lived celestial furnaces have captured the imagination of astronomers and astrobiologists alike, particularly as we've discovered that many harbor rocky, Earth-sized planets within their habitable zones. But groundbreaking new research suggests these abundant stellar systems may harbor a fundamental limitation that could prevent the emergence of complex life as we know it—they simply don't shine brightly enough to power the biological revolution that transformed Earth from a microbial world into one teeming with multicellular organisms.

This sobering conclusion emerges from a comprehensive study examining the relationship between stellar radiation output and the potential for oxygenic photosynthesis—the light-driven process that fundamentally altered Earth's atmosphere and paved the way for complex animal life. The research, titled "Dearth of Photosynthetically Active Radiation Suggests No Complex Life on Late M-Star Exoplanets," has been submitted to the journal Astrobiology by Joseph Soliz and William Welsh from San Diego State University's Department of Astronomy. Their findings present a compelling case that the universe's most common planetary systems may be forever locked in a primordial state, dominated by simple microbial life.

Earth's Oxygen Revolution: A Blueprint for Cosmic Life

To understand why red dwarf planets face such daunting odds, we must first appreciate one of the most transformative events in our planet's 4.5-billion-year history: the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE). Approximately 2.3 billion years ago, Earth's atmosphere underwent a dramatic chemical transformation when photosynthetic cyanobacteria—microscopic organisms that had evolved perhaps 700 million years earlier—began releasing oxygen as a metabolic waste product in sufficient quantities to fundamentally alter our planet's atmospheric composition.

This wasn't an overnight revolution. According to research from NASA's Astrobiology Program, it took approximately 2.5 billion years for oxygen levels to rise high enough to support the energy-intensive metabolic processes required by complex, multicellular organisms. The accumulation of free oxygen in the atmosphere eventually catalyzed the Cambrian Explosion—that extraordinary period roughly 541 million years ago when complex animal life rapidly diversified into the myriad forms we recognize today.

"The rise of oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere during the Great Oxidation Event occurred about 2.3 billion years ago. There is considerably greater uncertainty for the origin of oxygenic photosynthesis, but it likely occurred significantly earlier, perhaps by 700 million years," the researchers note in their analysis.

The critical question facing astrobiologists is whether this oxygen-driven pathway to complexity represents a universal template for life's evolution, or whether it's fundamentally dependent on receiving energy from a Sun-like star. As Soliz and Welsh demonstrate in their research, the answer may profoundly limit where we should expect to find intelligent life in our galaxy.

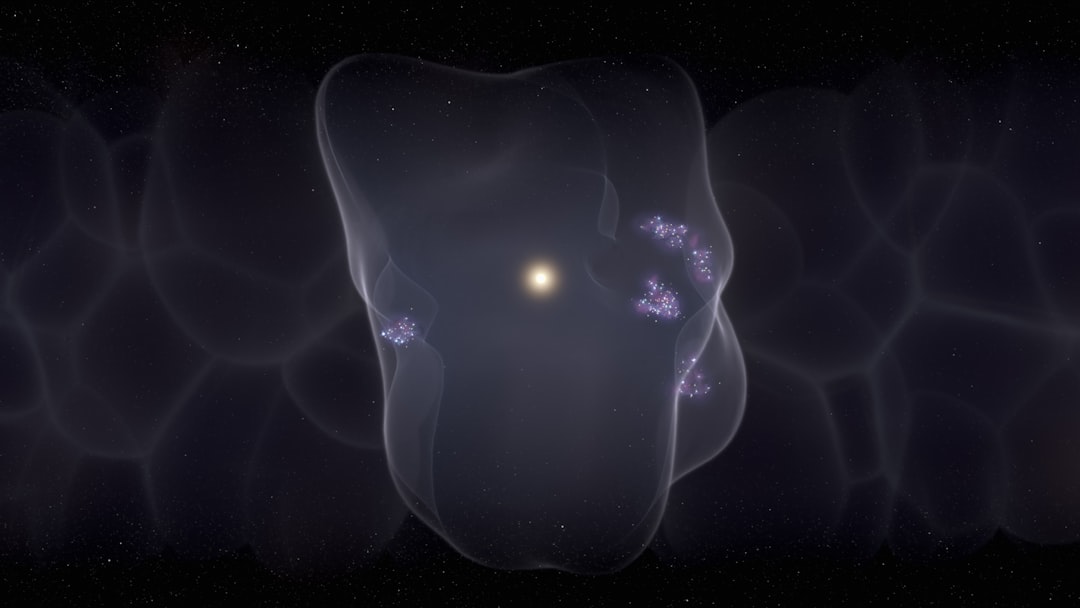

The TRAPPIST-1 Laboratory: Testing Earth Under Alien Suns

To investigate this question with scientific rigor, the researchers focused their analysis on one of the most intriguing planetary systems discovered in recent years: TRAPPIST-1. Located approximately 40 light-years from Earth, this ultracool red dwarf star hosts seven Earth-sized rocky planets, three of which orbit within the habitable zone—the region where liquid water could theoretically exist on a planet's surface. The system has been extensively studied by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and other observatories, making it an ideal testbed for theoretical models of habitability.

One planet in particular, TRAPPIST-1e, bears striking similarities to Earth in terms of size and orbital characteristics. The researchers posed an ingenious thought experiment: "What would happen if we replaced TRAPPIST-1e with the Archean Earth?"—essentially transplanting our planet's early biosphere into the dim red glow of this distant stellar system.

The results were stark. Despite orbiting within the habitable zone, an Earth-analog planet in TRAPPIST-1e's position would receive a mere 0.9% of the Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) that Earth receives from our Sun. This dramatic deficit exists because TRAPPIST-1, with an effective temperature of only 2,560 Kelvin (compared to the Sun's 5,778 Kelvin), emits most of its energy at wavelengths longer than the 400-700 nanometer range that terrestrial photosynthetic organisms have evolved to harness.

The Mathematics of Photons and Time

The researchers calculated that if the rate of oxygen generation scales proportionally with available photosynthetically active radiation, a Great Oxygenation Event on a TRAPPIST-1e analog would require approximately 63 billion years—more than four times the current age of the universe. This initial calculation painted an impossibly bleak picture for complex life around red dwarfs.

However, as with many phenomena in biology, the reality proves more nuanced than simple linear extrapolation suggests. The team incorporated several additional factors that significantly modified their timeline estimates:

- Photoinhibition effects: Photosynthesis doesn't scale linearly with light intensity. At higher light levels, photosynthetic efficiency actually decreases due to cellular damage—a phenomenon known as photoinhibition that varies considerably among different species and environmental conditions.

- Extended wavelength sensitivity: By expanding the upper wavelength limit of photosynthetically active radiation by just 50 nanometers (from 700 to 750 nm), the available photon count increases by a factor of 2.5, dramatically improving the energy budget for potential photosynthetic organisms.

- Adaptive evolution: Life on red dwarf planets might evolve photosynthetic machinery optimized for the specific spectral output of their host stars, potentially achieving greater efficiency than Earth's organisms would in such environments.

When these factors were incorporated into their models, the timeline for achieving a GOE-like event compressed considerably—to somewhere between one billion and five billion years. While still representing an extraordinarily long developmental period, this timescale falls within the realm of possibility for the oldest red dwarf planetary systems in our galaxy.

The Anoxygenic Advantage: When Oxygen Becomes Optional

Just as the researchers' refined models began to offer hope for oxygen-breathing complex life on red dwarf worlds, their analysis revealed an even more fundamental challenge: the competitive advantage of non-oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. These organisms, which evolved on Earth before their oxygen-producing cousins, use photosynthesis to generate metabolic energy without releasing oxygen as a byproduct.

The critical advantage these anoxygenic photosynthesizers possess in low-light environments is dramatic. They can utilize near-infrared light extending out to 1,100 nanometers—far beyond the range accessible to oxygenic cyanobacteria. In the dim red glow of an M-dwarf star, this extended spectral sensitivity provides access to 22 times as many photons as oxygenic photosynthesis can capture.

Research from the European Southern Observatory has shown that such competitive advantages can fundamentally shape ecosystem development. On a hypothetical Earth-analog orbiting TRAPPIST-1, anoxygenic photosynthesizers would likely dominate the ecosystem from the outset, monopolizing available light and nutrients. Under these conditions, oxygen-producing organisms might never gain a foothold, preventing atmospheric oxygen from ever reaching significant levels.

"With this huge light advantage, and because they evolved earlier, anoxygenic photosynthesizers would likely dominate the ecosystem. On a late M-star Earth-analog planet, oxygen may never reach significant levels in the atmosphere and a GOE may never occur, let alone a Cambrian Explosion. Thus complex animal life is unlikely," the researchers conclude.

A World of Microbial Mats

The picture that emerges from this analysis is one of permanently microbial worlds—planets where life exists, possibly even thrives, but remains locked in a simple, single-celled state. The researchers envision light-starved microbial mats growing slowly in shallow waters or damp terrestrial environments, extracting what meager energy they can from the weak photon flux of their dim red sun, with no evolutionary pressure driving the development of complex multicellular forms.

Assumptions, Uncertainties, and Future Discoveries

The authors acknowledge that their analysis rests on several key assumptions, most fundamentally that oxygen is necessary for complex life and that life would arise and develop on timescales roughly similar to Earth's history. However, they note that most of these unknown factors "scale out of the problem"—meaning they might affect the specific timeline but don't contradict the overall conclusion that red dwarf planets face severe challenges in developing complex life.

The research also highlights intriguing possibilities for future observational tests. Upcoming facilities like the James Webb Space Telescope and next-generation ground-based observatories may be capable of detecting atmospheric oxygen on nearby exoplanets through spectroscopic analysis. If oxygen were discovered in abundance on a late M-dwarf exoplanet's atmosphere, it would suggest that life has evolved mechanisms we haven't yet imagined—perhaps combining multiple near-infrared photons in novel ways to drive oxygenic photosynthesis.

"If future work shows we are incorrect, i.e., abundant oxygen is found in a late M-dwarf exoplanet's atmosphere, this would be extremely exciting. It would suggest that life has found a way to carry out oxygenic photosynthesis by combining several NIR photons—an astonishing feat," the researchers note.

Implications for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

This research carries profound implications for SETI efforts and our broader understanding of life's distribution in the universe. Red dwarfs comprise the vast majority of stars in our galaxy, and they host the majority of potentially habitable planets. If these worlds are indeed limited to simple microbial ecosystems, it dramatically narrows the cosmic real estate where we might expect to find intelligent life.

The findings complement other concerns about red dwarf habitability, particularly the issue of stellar flaring. Red dwarfs are known for producing powerful flares that could strip away planetary atmospheres, sterilizing any life that might have gained a foothold. Research from NASA's Exoplanet Exploration Program has documented numerous such events. The combination of insufficient photosynthetically active radiation and potentially destructive stellar activity presents a formidable double barrier to the emergence of complex life.

However, the universe is vast, and even if only Sun-like stars (G-type) and somewhat cooler K-type stars can host complex life, billions of potentially habitable worlds remain in our galaxy alone. The search for life beyond Earth continues, informed by increasingly sophisticated models of what makes a planet truly habitable—not just capable of hosting liquid water, but capable of providing the energy budget necessary for life to evolve from simple to complex forms.

The Road Ahead

As our observational capabilities continue to advance, we will soon be able to test these theoretical predictions against real data. The detection—or absence—of biosignature gases like oxygen and methane in the atmospheres of red dwarf exoplanets will provide crucial evidence for or against the scenarios outlined in this research. Each observation will refine our understanding of life's potential distribution across the cosmos and help answer one of humanity's most profound questions: Are we alone in the universe, or do we share it with other complex, perhaps intelligent, beings?

For now, this research serves as a sobering reminder that the universe's most common stellar systems may be fundamentally inhospitable to the kind of complex, oxygen-breathing life that has flourished on Earth. In the dim red light of these abundant stars, life—if it exists at all—may remain forever simple, a universe of microbes beneath alien skies that will never witness the emergence of creatures capable of contemplating their place in the cosmos.