In a groundbreaking development that could finally settle one of cosmology's most perplexing mysteries, astronomers have discovered two extraordinary supernovae whose light has been warped and magnified by gravitational lensing from massive galaxy clusters. These stellar explosions, designated SN Ares and SN Athena, offer an unprecedented opportunity to resolve the notorious Hubble Tension—the frustrating discrepancy between different measurements of how fast our universe is expanding. The discovery, announced at the 247th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, represents a potential breakthrough in our quest to understand the fundamental nature of cosmic expansion and the mysterious force of dark energy that drives it.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond simple measurement refinement. For decades, cosmologists have grappled with contradictory results when attempting to pin down the Hubble Constant—the value that describes the universe's expansion rate. This cosmic puzzle has created what scientists call the Hubble Tension, where measurements from the early universe yield significantly different values than those derived from observations of relatively nearby astronomical objects. The discrepancy isn't merely academic; it suggests either unknown systematic errors in our measurements or, more tantalizingly, the existence of new physics beyond our current understanding of the cosmos.

Understanding the Cosmic Expansion Puzzle

The story of measuring cosmic expansion begins with Edwin Hubble, the American astronomer who revolutionized our understanding of the universe in the 1920s. Hubble's observations revealed that galaxies are receding from us, with more distant galaxies moving away faster—a relationship that became known as Hubble's Law. The proportionality constant in this relationship, the Hubble Constant, has become one of the most sought-after values in all of cosmology. Yet despite nearly a century of increasingly sophisticated measurements, determining its precise value has proven remarkably elusive.

Modern astronomers employ two primary methods to measure the Hubble Constant, and herein lies the problem. When scientists analyze the Cosmic Microwave Background—the ancient light from just 380,000 years after the Big Bang—they calculate a value of approximately 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. However, when they use the Cosmic Distance Ladder, a method that relies on calibrating distances to progressively more distant objects including Type Ia supernovae, they arrive at a significantly different value: roughly 73 km/s/Mpc. This 9% discrepancy may seem small, but in the precision world of cosmology, it represents a crisis that threatens our fundamental understanding of the universe's composition and evolution.

The JWST VENUS Survey: Unveiling Cosmic Treasures

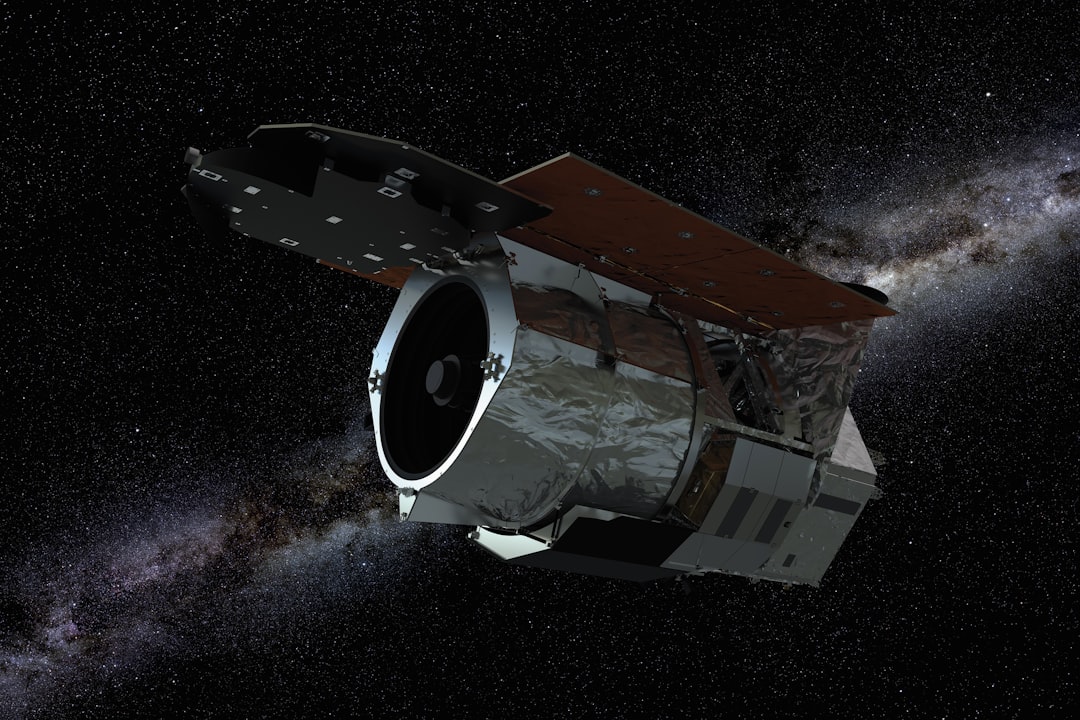

The discovery of SN Ares and SN Athena emerged from the VENUS program—an acronym for Vast Exploration for Nascent, Unexplored Sources—a ambitious survey utilizing the unprecedented capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope. Led by principal investigator Seiji Fujimoto, VENUS is conducting deep observations of 60 massive galaxy clusters, transforming these cosmic behemoths into natural telescopes through the phenomenon of gravitational lensing. Despite being only halfway through its observational campaign, VENUS has already yielded remarkable discoveries, including individual stars from the early universe, faint active black holes at the centers of primordial galaxies, and now these two exceptional supernovae.

Dr. Conor Larison, a post-doctoral researcher at the Space Telescope Science Institute and member of the VENUS collaboration, presented these findings at the American Astronomical Society meeting. His research reveals how these supernovae occupy a unique position in observational astronomy—they're simultaneously ancient relics from the early universe and future predictors of cosmic expansion. The gravitational lensing effect that makes them visible also creates a natural laboratory for testing our cosmological models with unprecedented precision.

"Strong gravitational lensing transforms galaxy clusters into nature's most powerful telescopes. VENUS was designed to maximally find the rarest events in the distant Universe, and these lensed supernovae are exactly the kind of phenomena that only this approach can reveal," explained Seiji Fujimoto, emphasizing the transformative potential of this observational strategy.

Gravitational Lensing: Einstein's Cosmic Magnifying Glass

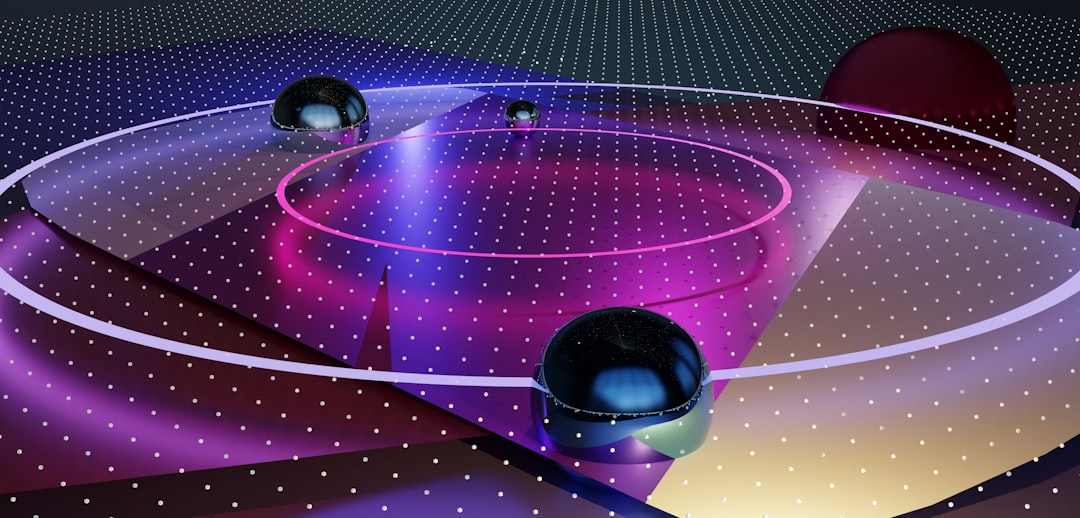

To understand why SN Ares and SN Athena are so valuable, we must first appreciate the remarkable physics of gravitational lensing. Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity predicts that massive objects warp the fabric of spacetime itself, causing light to follow curved paths as it passes nearby. When an extremely massive object like a galaxy cluster—containing the mass of hundreds or thousands of galaxies—lies between us and a more distant light source, it acts as a cosmic lens, bending and magnifying the light from background objects.

In the case of these supernovae, the galaxy clusters MJ0308 and MJ0417 serve as the lenses. SN Ares, which exploded when the universe was merely 4 billion years old, is lensed by the MJ0308 cluster. SN Athena, which detonated approximately 6.5 billion years ago, is magnified by MJ0417. The lensing effect doesn't just magnify these distant explosions—it splits their light into multiple images that take different paths around the lensing cluster. These different paths have different lengths, meaning light traveling along them arrives at Earth at different times, sometimes separated by years or even decades.

This time delay is the key to resolving the Hubble Tension. The delay depends on the expansion history of the universe, which in turn depends on the Hubble Constant and the properties of dark energy—the mysterious force that constitutes approximately 70% of the universe's energy budget and drives its accelerating expansion.

The Remarkable Case of SN Ares: A 60-Year Prediction

SN Ares presents an extraordinary opportunity for what Larison calls "a predictive experiment." The gravitational lensing models predict that additional images of this supernova will appear in approximately 60 years. This remarkably long time delay—unprecedented for strongly lensed supernovae—offers a unique chance to test our cosmological models with exceptional precision. Astronomers can use current observations to predict exactly when and where the next images should appear. When those images finally arrive in the 2080s, the actual timing will provide what Larison describes as "the most precise, single-step measurement of cosmology we have ever had the chance to make."

The beauty of this approach lies in its directness. Unlike many cosmological measurements that require multiple calibration steps, each introducing potential systematic errors, the time delay measurement is fundamentally simple: observe when the light arrives, compare it to predictions, and derive the Hubble Constant. The longer the time delay, the more sensitive the measurement becomes to the expansion history of the universe.

SN Athena: A Near-Term Test of Cosmic Expansion

While SN Ares represents a legacy for future astronomers, SN Athena offers more immediate gratification. Models predict that repeat images of Athena will arrive within 2 to 3 years, providing a much sooner opportunity to constrain the Hubble Constant. This near-term timeline makes Athena particularly valuable for addressing the current crisis in cosmology. As Justin Pierel, an Einstein Fellow at the Space Telescope Science Institute, explained in his presentation, this independent measurement arrives at a critical juncture when the cosmological community desperately needs new approaches to resolve the tension between different measurement methods.

"The predicted time delay to the next image of SN Athena of a few years will allow us to weigh in on the value of the Hubble Constant at a time when such an independent measurement is sorely needed. It may help to cement the possibility of new physics, or alternatively, point to unknown systematics in the best current cosmological analyses," noted Pierel, highlighting the discovery's potential to reshape our understanding of fundamental physics.

The Science Behind Type Ia Supernovae as Standard Candles

Both SN Ares and SN Athena belong to specific categories of stellar explosions that serve as standard candles—astronomical objects with well-understood intrinsic brightness. Type Ia supernovae, in particular, have become the workhorses of cosmological distance measurements. These explosions occur when a white dwarf star in a binary system accumulates matter from its companion until it reaches a critical mass threshold (approximately 1.4 solar masses, known as the Chandrasekhar limit). At this point, the white dwarf undergoes catastrophic thermonuclear detonation.

The remarkable uniformity of Type Ia supernovae—they all reach roughly the same peak brightness because they all explode at the same mass—makes them ideal distance indicators. By comparing their apparent brightness (how bright they appear from Earth) with their known absolute brightness, astronomers can calculate their distance using the inverse square law of light. This technique, combined with measurements of how much their light has been redshifted by cosmic expansion, allows scientists to map the expansion history of the universe.

Advanced Spectroscopic Analysis and Early Universe Physics

Beyond their value for measuring cosmic expansion, SN Ares and SN Athena offer unique insights into supernova physics in the early universe. The JWST's powerful infrared capabilities allowed the VENUS team to obtain detailed spectra of these ancient explosions—something that would have been impossible without the magnification provided by gravitational lensing. These spectra reveal the chemical composition, explosion mechanisms, and environmental conditions of supernovae from epochs when the universe was significantly younger and chemically different from today.

Larison emphasized this dual value in his presentation: "Supernova Ares is at a pretty large distance compared to other core-collapse supernovae that we're able to see, and the only reason that we're able to detect this and follow it up is because of the magnification effect of the strong lensing from the galaxy cluster. But apart from the SN physics, this is a strongly-lensed supernova, meaning that its galaxy actually appears multiple times."

Time-Domain Astronomy and the Long Game

The discovery of SN Ares and SN Athena exemplifies the emerging field of time-domain astronomy—the study of astronomical objects and phenomena that change over time. However, these supernovae represent an extreme case where the relevant timescales span not just hours, days, or years, but potentially decades and even billions of years. The explosions themselves occurred billions of years ago, yet their light continues to arrive at Earth in installments, separated by years or decades depending on the gravitational lensing geometry.

This temporal aspect introduces both challenges and opportunities. The 60-year wait for SN Ares's repeat images requires institutional commitment and careful planning to ensure continuity of observations across multiple generations of astronomers. It demands that current researchers document their predictions and methodologies with sufficient detail that scientists in 2084 can properly interpret the results. Yet this long baseline also provides unparalleled precision—the longer the time delay, the better these supernovae constrain cosmological parameters.

Dark Energy and the Future of Cosmology

At the heart of the Hubble Tension lies an even deeper mystery: the nature of dark energy. This enigmatic component, which comprises approximately 70% of the universe's total energy density, drives the accelerating expansion of the cosmos. Yet despite its dominance, we know virtually nothing about what dark energy actually is. Is it Einstein's cosmological constant—a property of space itself? Is it a dynamic field that changes over time? Or does its apparent existence signal that our understanding of gravity breaks down on cosmic scales?

The time delays measured from SN Ares and SN Athena are directly sensitive to the expansion history of the universe, which depends critically on dark energy's properties. As Larison noted, "The light from these background sources is bent and warped by these galaxy clusters, it arrives with a time delay that is directly related to the expansion history of the Universe. That expansion history depends on dark energy, which is 70% of the Universe."

Implications for New Physics

The resolution of the Hubble Tension could have profound implications for fundamental physics. If the tension persists even with new, independent measurements like those from SN Ares and SN Athena, it would strongly suggest that our standard cosmological model—known as Lambda-CDM—is incomplete. This could point toward exotic new physics: perhaps dark energy evolves over time, or maybe there are additional relativistic particles in the early universe that we haven't accounted for, or our understanding of gravity itself requires modification on cosmological scales.

Alternatively, if these new measurements help reconcile the different values of the Hubble Constant, it would suggest that subtle systematic errors have been affecting one or more of the traditional measurement methods. Either outcome would represent a significant advance in our understanding.

The Road Ahead: Predictions and Preparations

The discovery of SN Ares and SN Athena marks the beginning of a long-term observational campaign. For SN Athena, astronomers are now refining their lensing models and preparing for the anticipated appearance of repeat images within the next few years. This will require coordinated observations across multiple telescopes, including both space-based observatories like JWST and ground-based facilities equipped with advanced adaptive optics systems.

For SN Ares, the timeline extends much further into the future. Current researchers must carefully document their predictions, preserve the observational data, and establish protocols for the observations that will occur in 2084. Larison reflected on this temporal challenge: "It is hard to know what the key questions of the day will be in 60 years, but what is certain is that this reappearance will provide the most precise, single-step measurement of cosmology we have ever had the chance to make."

The VENUS survey continues its observations, with 30 more galaxy clusters yet to be studied. Given that the survey has already discovered these two remarkable supernovae while only halfway complete, additional lensed supernovae may yet be found, potentially with different time delays that could provide additional constraints on cosmic expansion.

A New Era in Precision Cosmology

The discovery of gravitationally lensed supernovae SN Ares and SN Athena represents more than just two interesting astronomical objects—it signals a new approach to one of cosmology's most fundamental questions. By leveraging the natural magnification provided by massive galaxy clusters and the time delays inherent in gravitational lensing, astronomers have created a novel method for measuring the Hubble Constant that is independent of traditional techniques and their associated systematic uncertainties.

These supernovae embody the patient, long-term nature of modern astronomy. While SN Athena promises results within a few years, SN Ares asks us to think across generations, to plan observations that won't be completed until today's graduate students are approaching retirement. This multigenerational approach to science reflects both the ambition and the humility required to understand the cosmos—the recognition that some questions are so fundamental, and some measurements so precise, that they require patience measured in decades.

As we await the arrival of additional images from these remarkable cosmic lighthouses, one thing is certain: whether they ultimately resolve the Hubble Tension or deepen the mystery, SN Ares and SN Athena will provide crucial insights into the nature of our expanding universe and the dark energy that drives it. In an era when cosmology increasingly demands precision measurements to distinguish between competing theoretical models, these gravitationally lensed supernovae offer exactly the kind of independent, high-precision data that could finally illuminate one of the universe