As humanity prepares to establish permanent settlements beyond Earth, one of the most pressing challenges facing space agencies and researchers worldwide is understanding how the extreme environment of space affects living organisms at every stage of development. While we've learned much about the effects of microgravity and cosmic radiation on adult astronauts, particularly through landmark studies like NASA's Twins Study, critical questions remain about how these conditions impact biological development from the earliest stages of life. Now, a groundbreaking experiment developed by scientists at the University of Leicester's Space Park promises to shed new light on these fundamental questions using an unlikely but scientifically valuable research subject: microscopic worms.

The Fluorescent Deep Space Petri-Pod (FDSPP) represents a new generation of compact, autonomous space laboratories designed to conduct sophisticated biological experiments aboard the International Space Station and in the harsh vacuum of space. This innovative platform will carry colonies of C. elegans nematodes—tiny worms that have become one of science's most valuable model organisms—on a 15-week journey that will expose them to conditions no Earth-bound laboratory can replicate. The data gathered from this mission could prove crucial for developing medical countermeasures to protect future astronauts and determining whether life can successfully reproduce and develop in space environments.

Understanding the Biological Challenges of Long-Duration Spaceflight

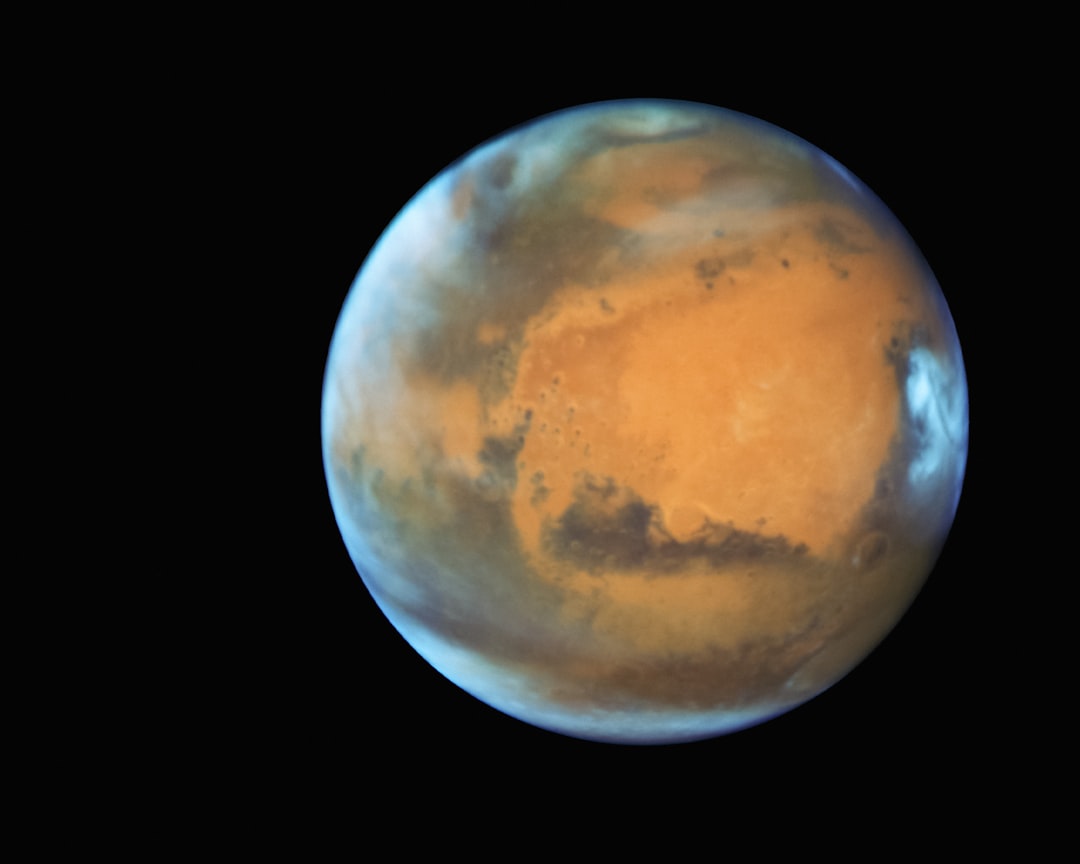

The human body evolved over millions of years to function under Earth's gravity and protected by our planet's magnetic field and atmosphere. When astronauts venture into space, they enter an environment fundamentally hostile to terrestrial life. Microgravity conditions aboard spacecraft and space stations cause a cascade of physiological changes that begin almost immediately upon reaching orbit. Bones lose density at a rate of approximately 1-2% per month, muscle mass deteriorates despite rigorous exercise regimens, and fluids shift upward in the body, affecting vision and intracranial pressure.

Beyond microgravity, cosmic radiation poses an even more insidious threat. Outside Earth's protective magnetosphere, astronauts are bombarded by high-energy particles from solar flares and galactic cosmic rays that can penetrate spacecraft hulls and human tissue. This radiation exposure increases cancer risk, accelerates cellular aging, and can cause damage to the central nervous system that may lead to cognitive impairment and degenerative diseases. According to research from NASA's Human Research Program, radiation remains one of the most significant barriers to long-duration missions to Mars and beyond.

What remains less understood, however, is how these space environment factors affect organisms during their developmental stages—from conception through maturation. Can embryos develop normally in microgravity? Does radiation exposure during early development cause more severe genetic damage than in adult organisms? These questions are critical for any vision of humanity as a truly spacefaring species, capable of establishing self-sustaining colonies on the Moon, Mars, or in orbital habitats.

Why Worms Make Perfect Space Research Subjects

The choice of Caenorhabditis elegans as the primary research subject for the FDSPP experiment is far from arbitrary. These microscopic nematodes, measuring just about 1 millimeter in length, have been extensively studied in laboratories worldwide for decades and are considered one of the premier model organisms in biological research. In fact, research using C. elegans has contributed to three Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine, underscoring their scientific value.

These tiny worms offer several crucial advantages for space biology research. First, they have a rapid life cycle of just three days from egg to reproductive adult, allowing researchers to observe multiple generations and developmental stages within a relatively short mission duration. Second, despite their simplicity, C. elegans share many fundamental biological processes with humans, including mechanisms for muscle development, neuron function, and aging. Approximately 60-80% of human genes have functional equivalents in these worms, making them remarkably relevant for understanding human biology.

Additionally, C. elegans are transparent, allowing scientists to observe their internal structures and cellular processes in real-time without invasive procedures. The worms can also be genetically modified to express fluorescent markers in specific tissues or cells, enabling researchers to track particular biological responses to space conditions with unprecedented precision. Previous research using these organisms has already revealed insights into muscle atrophy mechanisms that parallel those observed in astronauts, as documented in studies published in Nature's npj Microgravity journal.

Engineering Innovation: Inside the Fluorescent Deep Space Petri-Pod

The FDSPP represents a remarkable feat of miniaturization and engineering, packing sophisticated life-support systems, imaging equipment, and data collection capabilities into a compact unit measuring just 10x10x30 centimeters and weighing approximately 3 kilograms. Developed by the multidisciplinary team at Space Park Leicester with funding from the UK Space Agency, this self-contained laboratory builds upon Leicester's impressive 65-year heritage in space instrumentation and experimentation.

At the heart of the system are 12 individual Petri-Pods, each functioning as an isolated micro-environment capable of maintaining stable atmospheric conditions, temperature, and nutrient delivery for its biological cargo. Four of these pods will house the C. elegans colonies, while the remaining eight will contain various microorganisms, other test subjects, and materials being evaluated for their response to the space environment. Each pod is sealed to maintain its internal atmosphere even when the entire unit is exposed to the vacuum of space outside the ISS.

"The Fluorescent Deep Space Petri-Pod has been engineered using the electronic, engineering, software, and science expertise of the Space Park Leicester team, based around the 65-year heritage of space experiments at Leicester. This mission to the International Space Station will demonstrate the flight readiness of FDSPP, and we believe its success will help position the UK amongst the global leaders in life sciences research for future low Earth orbit, Lunar, and Mars missions planned by Space Agencies and private companies," explained Professor Mark Sims, project manager for the FDSPP experiment.

The worms receive their nutrition through an agar carrier medium—the same gelatinous substance used in countless microbiology laboratories on Earth to culture microorganisms in Petri dishes. This agar not only provides nutrients but also maintains proper hydration levels for the organisms throughout the mission. The system's imaging capabilities include both white-light and fluorescent microscopy, allowing researchers to capture detailed time-lapse videos and still images of the worms' behavior, development, and health status throughout the experiment.

Mission Profile: From Launch to Deep Space Exposure

The FDSPP's journey to space is scheduled for April 2026, when it will launch to the ISS as part of a commercial cargo resupply mission, with launch services coordinated through Houston-based Voyager Technologies. The mission profile is carefully designed to maximize scientific return while ensuring the safety of both the experiment and the ISS crew.

Upon arrival at the station, the unit will initially remain inside the pressurized modules where astronauts can monitor its performance and ensure all systems are functioning correctly. During this initial phase, the fluorescent markers installed in the worms' neural tissues will be activated, allowing researchers on the ground to begin collecting baseline data on the organisms' health and behavior in the microgravity environment of the ISS interior.

After this checkout period, the FDSPP will be deployed outside the station using the robotic arm or through an airlock, beginning its 15-week exposure to the deep space environment. During this extended period, the experiment will face the full brunt of conditions that future deep space missions will encounter: hard vacuum, unfiltered cosmic radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations between sunlit and shadowed periods, and continuous microgravity. Throughout this time, the unit's sensors will continuously monitor internal pod temperature and pressure, external environmental conditions, and cumulative radiation dose using integrated dosimeters.

As Professor Tim Etheridge, principal investigator and science lead from the University of Exeter, emphasized:

"Performing biology research in space comes with many challenges, but is vital to humans safely living in space. This hardware, made possible through strong collaboration between biologists around the world and engineers at Space Park Leicester, will offer scientists a new way to understand and prevent health changes in deep space on any launch vehicle."

Scientific Objectives and Expected Discoveries

The FDSPP experiment aims to address several critical knowledge gaps in our understanding of space biology. The primary objectives include:

- Developmental Biology in Microgravity: Researchers will observe whether C. elegans can complete their full life cycle in space, from egg through larval stages to reproductive adulthood. This will provide crucial data on whether fundamental developmental processes can proceed normally without gravity's influence.

- Radiation Effects on Living Tissue: By comparing worms in different pods and correlating their health markers with measured radiation doses, scientists can quantify the biological impact of cosmic radiation exposure at various intensities and durations.

- Neuromuscular Function: The fluorescent markers in the worms' nervous systems will allow detailed observation of neural activity and muscle function, potentially revealing mechanisms of space-induced muscle atrophy that could inform countermeasure development for human astronauts.

- Aging Processes: C. elegans research has already contributed significantly to our understanding of aging on Earth. Observations of how space conditions affect aging-related cellular processes could provide insights relevant to both space medicine and terrestrial gerontology.

- Genetic Stability: Post-flight analysis of the worms' DNA will reveal the extent of radiation-induced genetic damage and the organisms' ability to repair such damage, information critical for assessing risks to future space colonists.

Broader Implications for Space Colonization

While the FDSPP experiment focuses on microscopic worms, its implications extend far beyond nematode biology. The data gathered will contribute to answering one of the most profound questions facing humanity's spacefaring ambitions: Can life reproduce and develop normally in space? This question is fundamental to any serious plans for establishing permanent human settlements beyond Earth, whether in lunar bases, Martian colonies, or free-floating space habitats.

The research also has immediate practical applications for protecting astronaut health during long-duration missions. Understanding the mechanisms by which space conditions affect muscle, bone, and neural tissue at the cellular and molecular level will enable the development of more effective medical countermeasures. While current approaches rely heavily on exercise regimens—astronauts aboard the ISS typically spend two hours daily on resistance and cardiovascular exercise—pharmaceutical or genetic interventions may prove necessary for missions lasting years rather than months.

The FDSPP's modular, scalable design also represents a new paradigm for space biology research. Rather than requiring large, expensive dedicated facilities, this compact platform demonstrates that sophisticated biological experiments can be conducted using relatively small, cost-effective hardware. This approach could democratize space biology research, making it accessible to more institutions and researchers worldwide, as highlighted in recent European Space Agency initiatives to expand life sciences research in space.

Looking Toward the Future of Space Life Sciences

The FDSPP mission represents just one step in a broader international effort to understand how life functions beyond Earth. Organizations like NASA's Biological and Physical Sciences Division are coordinating an expanding portfolio of space biology research, from studying plant growth in lunar regolith simulants to investigating how microorganisms might be harnessed for life support systems in future habitats.

As we look toward an era of renewed lunar exploration through NASA's Artemis program and ambitious plans for human Mars missions in the 2030s, experiments like the FDSPP provide essential foundational knowledge. The data gathered from these C. elegans worms may ultimately help determine whether children born on Mars could develop normally, whether space-based agriculture can sustain permanent settlements, and what medical interventions will be necessary to keep astronauts healthy during multi-year interplanetary voyages.

The collaboration between the University of Leicester, the University of Exeter, the UK Space Agency, and commercial partners also exemplifies the increasingly international and public-private nature of space research. As Professor Sims noted, success in this mission could position the UK as a leader in space life sciences, contributing British expertise to the global effort to make humanity a multi-planetary species.

When the FDSPP returns to Earth after its 15-week exposure to the space environment, researchers will conduct detailed post-flight analyses of the surviving organisms, examining their genetic material, cellular structures, and any offspring produced during the mission. These findings, combined with the continuous monitoring data collected throughout the flight, will be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals and shared with the international space research community, adding another crucial piece to the complex puzzle of how life can thrive beyond our home planet.