Astronomers have finally cracked one of the universe's most perplexing puzzles: the origin of extraordinarily brilliant blue flashes that briefly outshine entire galaxies before disappearing into cosmic darkness. These enigmatic events, known as luminous fast blue optical transients (LFBOTs), have mystified the scientific community since their discovery, sparking intense debate about whether they represented exotic types of supernovae or something entirely unprecedented in our understanding of stellar death.

The breakthrough came through observations of AT 2024wpp, an LFBOT detected approximately 1.1 billion light-years from Earth that shattered previous records for brightness and energy output. According to research published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, this cosmic beacon released 100 times more energy in its first 45 days than a typical supernova emits over its entire visible lifetime—a staggering output that definitively points to an extraordinary power source lurking at the heart of these mysterious events.

What astronomers discovered represents a watershed moment in high-energy astrophysics: these brilliant transients are powered by intermediate-mass black holes violently consuming their stellar companions. This finding not only solves the LFBOT mystery but also provides the first electromagnetic confirmation of a black hole class that has remained tantalizingly elusive despite indirect evidence from gravitational wave detections by LIGO.

The Cosmic Engines Behind the Brightest Flashes

The research team's analysis reveals that LFBOTs occur when an intermediate-mass black hole—potentially weighing between 100 and 100,000 solar masses—completely destroys its massive stellar partner in a catastrophic tidal disruption event. These black holes occupy a fascinating middle ground in the cosmic hierarchy, bridging the gap between stellar-mass black holes (formed from individual collapsing stars) and the supermassive black holes that anchor galactic centers.

"For the first time we have confirmed that these transients require some sort of central energy source beyond what a supernova can produce normally on its own," explains Natalie LeBaron, a graduate student at UC Berkeley and member of the research team.

The existence of intermediate-mass black holes has long been predicted by theoretical models, but observational confirmation has proven elusive. While NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and other facilities have detected tantalizing hints of these objects, AT 2024wpp provides the most compelling electromagnetic evidence to date. This discovery opens an entirely new window for studying these enigmatic cosmic titans.

Anatomy of a Stellar Catastrophe

The scenario that produces an LFBOT is both extraordinarily violent and remarkably complex, involving a delicate cosmic dance that can last millions of years before its explosive conclusion. Researchers have reconstructed the following sequence of events leading to these brilliant outbursts:

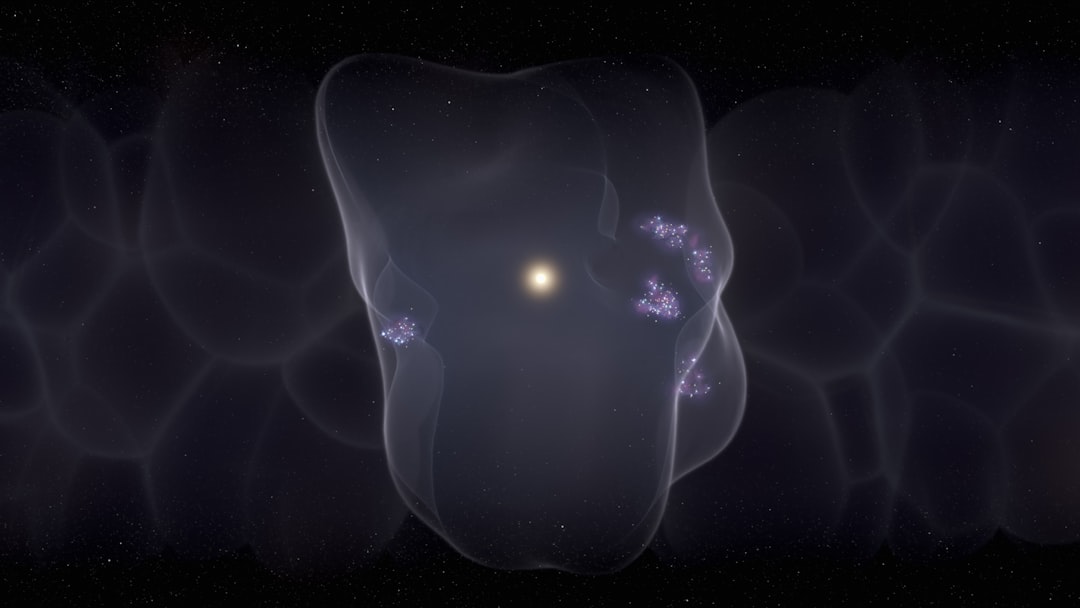

The process begins with a long-lived binary system consisting of an intermediate-mass black hole and a massive stellar companion. Over extended timescales, the black hole gradually siphons material from its partner through a process called Roche lobe overflow, where the star's outer layers extend beyond its gravitational boundary and fall toward the black hole. This stolen material doesn't immediately plunge into the black hole; instead, it accumulates in a distant halo, forming a reservoir of gas that orbits patiently, waiting for the final act of this cosmic drama.

The climax arrives when the companion star—likely more than ten times the Sun's mass—ventures too close to the black hole's gravitational influence. At this critical distance, known as the tidal disruption radius, the differential gravitational forces across the star become so extreme that they literally tear the stellar body apart. The process is called spaghettification by astrophysicists, a term that vividly captures how the star is stretched into long streams of plasma.

The Multi-Wavelength Fireworks Display

What happens next produces the spectacular light show that characterizes LFBOTs. The freshly disrupted stellar material becomes violently entangled with the black hole's rapidly rotating accretion disk, colliding with the pre-existing gas reservoir at velocities approaching significant fractions of light speed. These high-energy collisions generate intense bursts of X-ray, ultraviolet, and blue optical light—the signature blue flash that gives these events their name.

Simultaneously, the black hole's powerful magnetic fields channel some of the infalling material toward its poles, accelerating it to approximately 40 percent of light speed and launching it into space as relativistic jets. When these jets slam into the surrounding interstellar medium, they produce radio emissions detectable by facilities like the Very Large Array, providing crucial multi-wavelength observations that help astronomers piece together the complete picture.

The Wolf-Rayet Connection: Solving the Hydrogen Puzzle

One of the most intriguing aspects of AT 2024wpp involves the identity of the destroyed companion star. Spectroscopic analysis revealed unusually weak hydrogen signatures, a characteristic that had puzzled astronomers studying earlier LFBOTs. The research team now believes the companion was likely a Wolf-Rayet star—an evolved stellar behemoth that has already shed most of its hydrogen envelope through powerful stellar winds.

Wolf-Rayet stars represent a brief but spectacular phase in the evolution of the most massive stars in the universe. These objects, which can reach temperatures exceeding 100,000 Kelvin at their surfaces, blow off their outer layers at rates of up to one solar mass every 100,000 years. By the time such a star meets its fate in a tidal disruption event, it has already lost much of its hydrogen, naturally explaining the weak hydrogen signatures observed in AT 2024wpp.

This connection to Wolf-Rayet stars also helps explain why LFBOTs are so rare. These massive evolved stars represent only a tiny fraction of the stellar population, and they must be in precisely the right binary configuration with an intermediate-mass black hole—a combination that occurs only under exceptional circumstances in the cosmic census.

Revolutionary Observations from Keck Observatory

The definitive evidence that cracked the LFBOT mystery came from observations conducted at the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. Using the facility's Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS), astronomers detected extremely faint hydrogen and helium signatures exhibiting an unusual double-peaked spectral pattern. This distinctive feature provided the smoking gun that the explosion wasn't spherically symmetric—as would be expected from a conventional supernova—but instead lopsided and asymmetric.

The double-peaked pattern indicates material moving both toward and away from Earth at high velocities, consistent with gas swirling in an accretion disk viewed at an angle rather than expanding uniformly in all directions. This observation alone ruled out standard supernova models and pointed toward an accretion-powered scenario.

Perhaps even more revealing was data from Keck's Near Infrared Echellette Spectrograph (NIRES), obtained approximately 24 days after the initial detection. The instrument uncovered an unusual excess of near-infrared light—a feature observed only once before in LFBOTs. This infrared excess likely originates from dust grains forming in the cooling ejecta or from pre-existing dust in the system being heated by the intense radiation from the event.

Opening New Observational Windows

The near-infrared discovery has profound implications for future LFBOT studies. It suggests that observations in the mid-infrared wavelength range—particularly with facilities like the James Webb Space Telescope—could reveal additional physical processes occurring in these events. Webb's unprecedented infrared sensitivity and spectroscopic capabilities make it ideally suited to detect and characterize the thermal emission from dust and cooler gas components that remain invisible to optical telescopes.

Implications for Black Hole Demographics and Galaxy Evolution

The confirmation that LFBOTs are powered by intermediate-mass black holes has far-reaching implications beyond simply solving a cosmic mystery. These observations provide a new technique for finding and studying a population of black holes that has remained largely hidden from astronomers despite their theoretical importance.

Intermediate-mass black holes are thought to play crucial roles in several astrophysical contexts. They may serve as the seeds for supermassive black holes that grow to billions of solar masses in galactic centers. They could also be the primary inhabitants of globular clusters—dense stellar systems orbiting galaxies—where their gravitational influence shapes the cluster's evolution. Understanding their abundance and distribution helps astronomers reconstruct the history of structure formation in the universe.

Furthermore, the discovery that these black holes can lurk in binary systems for extended periods before catastrophically consuming their companions raises new questions about stellar evolution in extreme environments. The gradual mass transfer process that precedes the final disruption may fundamentally alter both the star's evolution and the black hole's growth history.

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

While AT 2024wpp has provided unprecedented insights into LFBOTs, numerous questions remain. Key areas for future investigation include:

- Population statistics: How common are intermediate-mass black holes in binary systems, and what fraction eventually produce observable LFBOTs? Systematic surveys with facilities like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will be essential for answering these questions.

- Jet physics: What determines the properties of the relativistic jets launched during these events, and how do they interact with their surroundings? Multi-wavelength monitoring campaigns will be crucial for understanding jet formation and evolution.

- Progenitor diversity: Are all LFBOTs powered by intermediate-mass black holes disrupting Wolf-Rayet stars, or do other configurations also produce similar observational signatures? Detailed spectroscopic studies of additional events will help map the full range of LFBOT progenitors.

- Formation channels: How do intermediate-mass black holes form in the first place, and how do they end up in binary systems with massive stars? This question connects to fundamental issues in stellar dynamics and black hole formation theory.

A New Era in Transient Astronomy

The solution to the LFBOT mystery exemplifies the power of modern time-domain astronomy—the systematic monitoring of the sky to detect and characterize transient events. As next-generation facilities come online, including the Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time and increasingly sophisticated follow-up capabilities, astronomers expect to discover many more LFBOTs and related phenomena.

Each new detection will refine our understanding of these extreme events and the exotic objects that power them. The combination of rapid discovery, multi-wavelength follow-up observations, and sophisticated theoretical modeling promises to transform our understanding of the most energetic processes in the universe.

The story of AT 2024wpp demonstrates that even in an era when astronomical surveys detect thousands of transient events daily, nature still has the capacity to surprise us with phenomena that challenge our theoretical frameworks and push observational capabilities to their limits. As we continue to probe the universe's most extreme environments, we can expect many more such revelations—each one illuminating another facet of the cosmos's remarkable complexity and beauty.