The quest to discover habitable worlds beyond our solar system has evolved dramatically since astronomers first confirmed the existence of exoplanets in the 1990s. What began as a straightforward search for planets in the "habitable zone"—the region around a star where liquid water could exist on a planet's surface—has now become a far more sophisticated endeavor. Today, researchers are introducing new frameworks for categorizing potentially life-bearing worlds, recognizing that the universe's diversity demands more nuanced definitions than our early, Earth-centric models could provide.

A groundbreaking study submitted to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society by researchers from the University of Birmingham and the University of Oxford introduces the concept of a "temperate zone"—a broader classification that encompasses worlds receiving moderate stellar radiation, even if they don't fit traditional habitable zone criteria. This research, led by Madison Scott and Georgina Dransfield, also announces the discovery of two fascinating exoplanets orbiting fully convective M dwarf stars, adding crucial data points to our growing catalog of potentially interesting worlds.

The study represents a significant shift in how astronomers approach the search for life beyond Earth, acknowledging that habitability may exist in forms we haven't yet imagined. By expanding our definitions and refining our search parameters, scientists are casting a wider net that could reveal unexpected havens for life in the cosmos.

Evolution of Habitable Zone Concepts in Exoplanetary Science

When the exoplanet revolution began with the discovery of 51 Pegasi b in 1995, astronomers operated with relatively simple criteria. The initial habitable zone definition focused exclusively on orbital distance—any planet receiving enough stellar energy to maintain liquid water on its surface qualified as potentially habitable. This straightforward approach served early researchers well, providing a clear framework for prioritizing targets in an overwhelming universe of possibilities.

However, as detection methods improved and the exoplanet catalog expanded exponentially—now exceeding 5,000 confirmed worlds cataloged by NASA's Exoplanet Archive—scientists recognized the need for more sophisticated classifications. The field developed two refined categories: the optimistic habitable zone and the conservative habitable zone.

The optimistic habitable zone extends both inward and outward from the traditional boundaries. Its inner edge accounts for planetary rotation patterns that could prevent runaway greenhouse effects, while its outer limit considers geothermal heating from a planet's interior that might warm worlds far from their stars. Conversely, the conservative habitable zone employs stricter criteria, with an inner boundary defined by the onset of greenhouse conditions and an outer limit determined by carbon dioxide condensation—the point where atmospheric CO₂ freezes out, eliminating a crucial greenhouse gas needed to retain warmth.

"As the diversity of exoplanets continues to grow, it is important to revisit assumptions about habitability and classical HZ definitions," the research team emphasizes in their paper, highlighting the dynamic nature of exoplanetary science.

Introducing the Temperate Zone Framework

The new research introduces an expanded "temperate zone" concept, defined by instellation flux values between 0.1 and 5 times Earth's solar constant. To understand this metric, consider that instellation flux measures the amount of stellar energy reaching a planet's surface, expressed in watts per square meter (W/m²). Earth receives approximately 1,361 W/m² at the top of its atmosphere—a value known as the solar constant. The temperate zone therefore encompasses worlds receiving between roughly 136 W/m² and 6,805 W/m², a deliberately broad range designed to capture planets with diverse potential for interesting atmospheric and surface conditions.

This framework intentionally diverges from strict habitability criteria. While the conservative habitable zone focuses narrowly on liquid water sustainability, the temperate zone classification identifies planets receiving moderate stellar radiation levels that warrant further investigation. This distinction proves crucial for several reasons:

- Atmospheric diversity: Planets outside traditional habitable zones might harbor exotic atmospheric chemistries that could support alternative biochemistries or provide insights into planetary evolution

- Observational priorities: The temperate zone helps astronomers identify targets suitable for atmospheric characterization with current and future telescopes, regardless of strict habitability criteria

- Theoretical flexibility: As our understanding of life's requirements evolves, having a broader classification ensures we don't prematurely exclude potentially interesting worlds

- Comparative planetology: Studying temperate planets across various sizes and compositions enhances our understanding of planetary processes and atmospheric retention

The research emerges from the TEMPOS survey (Temperate M Dwarf Planets With SPECULOOS), which leverages the SPECULOOS network—the Search for habitable Planets EClipsing ULtra-cOOl Stars. This coordinated ground-based effort specifically targets tiny, dim M dwarf stars, recognizing these stellar lightweights as prime real estate for finding temperate worlds accessible to detailed study.

Why M Dwarf Stars Matter for Temperate Planet Discovery

The focus on mid- to late-type M dwarf stars—red dwarfs with effective temperatures at or below 3,400 Kelvin—reflects strategic thinking about where temperate planets are most detectable. These cool, small stars comprise approximately 75% of all stars in our galaxy, making them statistically important targets. More crucially, their physical properties create ideal conditions for finding and studying temperate planets.

Planet equilibrium temperature depends on both orbital distance and stellar effective temperature. Because M dwarfs burn at much cooler temperatures than our Sun, their temperate zones lie much closer to the star. This proximity means temperate planets around M dwarfs have shorter orbital periods—often just days or weeks rather than months or years—making them transit more frequently and thus easier to detect and confirm.

Additionally, the small size of M dwarfs amplifies the observational signals produced by transiting planets. When a planet passes in front of its star, it blocks a percentage of the star's light proportional to the ratio of their cross-sectional areas. A terrestrial planet transiting a small M dwarf blocks a much larger fraction of light than the same planet would transiting a Sun-like star, making the detection signal stronger and more reliable.

Fully convective M dwarfs—stars where heat transport occurs entirely through convection rather than radiation—represent a particularly interesting subset. These stars exhibit unique magnetic field properties and activity patterns that could significantly influence the atmospheric evolution of their planets, making them priority targets for understanding star-planet interactions.

Meet the New Temperate Worlds: TOI-6716 b and TOI-7384 b

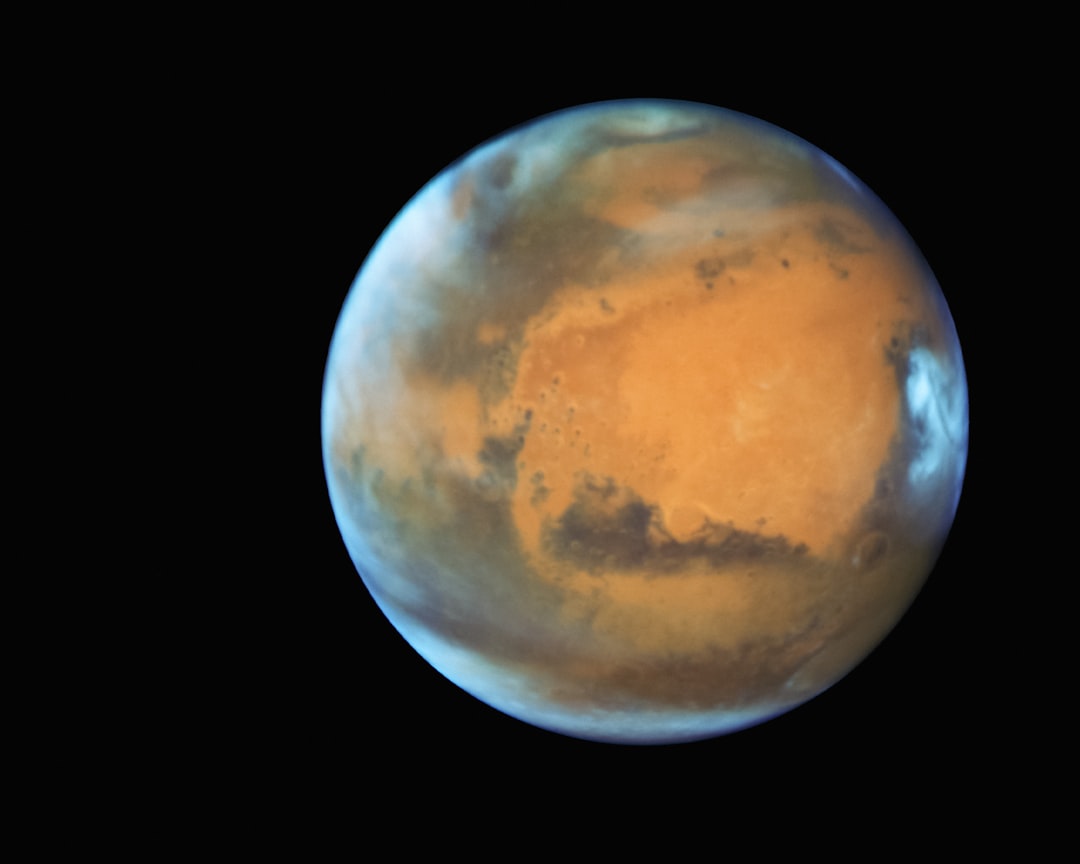

The research announces two newly characterized temperate exoplanets that expand our catalog of interesting worlds orbiting M dwarf stars. TOI-6716 b measures between 0.91 and 1.05 Earth radii, placing it firmly in the terrestrial planet category. Its size strongly suggests a rocky composition similar to Earth, Venus, or Mars, making it particularly intriguing for atmospheric studies. Despite receiving more stellar radiation than Earth—positioning it near the inner, hotter edge of the temperate zone—TOI-6716 b could potentially retain an atmosphere if its formation and evolution followed favorable pathways.

The planet's Transmission Spectroscopy Metric (TSM)—a value that predicts how suitable a planet is for atmospheric characterization—rivals that of the famous TRAPPIST-1 planets, a system of seven Earth-sized worlds orbiting an ultra-cool dwarf star that has become a cornerstone of exoplanet atmospheric research. This favorable TSM suggests that the James Webb Space Telescope could potentially detect and characterize TOI-6716 b's atmosphere if one exists, revealing its composition and potentially detecting biosignature gases.

TOI-7384 b presents a different profile entirely. This sub-Neptune world measures between 3.35 and 3.77 Earth radii—significantly larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. Planets in this size range remain enigmatic; they could possess rocky cores enveloped in thick hydrogen-helium atmospheres, or they might be "water worlds" with deep global oceans overlying rocky interiors. Some might even represent "Hycean worlds"—a recently proposed planet type featuring hydrogen-rich atmospheres above liquid water oceans, potentially offering habitable conditions despite exotic atmospheric compositions.

The researchers note that while neither planet falls within even the optimistic habitable zones of their host stars, they occupy "an otherwise sparse region of temperate planet parameter space." This positioning proves valuable for comparative studies, allowing astronomers to examine how planets respond to various instellation levels and how atmospheric properties vary across the temperate regime.

Observational Strategy and the TESS-SPECULOOS Partnership

The discovery of these temperate worlds exemplifies the power of coordinated observational campaigns combining space-based and ground-based facilities. NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) serves as the primary discovery engine, conducting an all-sky survey that monitors hundreds of thousands of stars for the telltale brightness dips caused by transiting planets. TESS's wide-field cameras and continuous monitoring capabilities make it exceptionally efficient at identifying planet candidates.

However, TESS observations alone cannot fully characterize these worlds. The SPECULOOS network—consisting of multiple robotic telescopes strategically positioned around the globe—provides crucial follow-up observations. These dedicated facilities can monitor target stars with higher precision and for extended periods, confirming planetary candidates, refining orbital parameters, and measuring planetary radii with greater accuracy. The SPECULOOS telescopes' focus on ultra-cool dwarf stars complements TESS's broader survey, creating a synergistic partnership that maximizes scientific return.

This collaborative approach addresses a fundamental challenge in exoplanet science: distinguishing genuine planetary transits from false positives caused by eclipsing binary stars, stellar activity, or instrumental artifacts. By combining multiple observation types from different facilities, astronomers can confidently validate discoveries and build robust catalogs of well-characterized temperate planets suitable for detailed follow-up studies.

Implications for Atmospheric Characterization and Future Research

The ultimate goal of identifying temperate exoplanets extends beyond mere cataloging—these worlds represent prime targets for atmospheric characterization, the next frontier in exoplanet science. When a planet transits its star, some starlight filters through the planet's atmosphere (if one exists), and different atmospheric molecules absorb specific wavelengths of light. By analyzing this transmitted light with high-resolution spectrographs, astronomers can identify atmospheric constituents, potentially detecting water vapor, methane, carbon dioxide, and even biosignature gases like oxygen or phosphine.

The James Webb Space Telescope, with its unprecedented infrared sensitivity and spectroscopic capabilities, has already begun revolutionizing atmospheric studies of exoplanets. TOI-6716 b's favorable TSM suggests it could join the ranks of planets with measured atmospheric properties, providing insights into how terrestrial planets retain or lose their atmospheres when subjected to intense stellar radiation. Similarly, TOI-7384 b's size and predicted mass make it an excellent candidate for probing sub-Neptune atmospheres, helping astronomers understand these mysterious intermediate-sized worlds that have no analog in our solar system.

Future facilities will expand these capabilities further. The Extremely Large Telescope, currently under construction in Chile, will provide even greater sensitivity for atmospheric studies. NASA's proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory, though still in early planning stages, aims to directly image and characterize potentially habitable exoplanets, complementing the transit-based studies that currently dominate the field.

"Together these discoveries show the power of combining TESS with coordinated ground-based efforts to build a catalogue of temperate planets around fully convective M dwarfs for atmospheric studies in the coming decade," the researchers conclude, highlighting the long-term vision driving this work.

Broadening Our Conception of Habitability

The introduction of the temperate zone concept reflects a maturing field grappling with increasingly complex questions about life's potential distribution throughout the universe. Early exoplanet research necessarily adopted Earth-centric assumptions—we had only one example of a life-bearing world to guide our search. As our knowledge expands, so too must our frameworks for categorizing and prioritizing targets.

Recent discoveries have challenged traditional assumptions about where life might arise. The detection of phosphine in Venus's atmosphere (though still debated) suggested that even hellishly hot worlds with crushing surface pressures might harbor airborne microbes. The discovery of subsurface oceans on Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus demonstrated that liquid water—and potentially life—could exist far beyond traditional habitable zones, sustained by tidal heating rather than stellar radiation.

The temperate zone framework acknowledges these complexities while maintaining practical focus. By identifying planets receiving moderate stellar radiation, regardless of strict habitability criteria, astronomers create a broader target list for atmospheric studies that could reveal unexpected forms of habitability or provide crucial data points for understanding planetary evolution. As our observational capabilities improve and our theoretical models become more sophisticated, today's "merely temperate" planets might prove to be tomorrow's most intriguing targets in the search for life beyond Earth.

The discovery of TOI-6716 b and TOI-7384 b, along with the conceptual framework of temperate zones, represents more than just technical progress in exoplanet characterization. It embodies a philosophical evolution in how we approach one of humanity's most profound questions: Are we alone in the universe? By expanding our definitions, refining our search strategies, and leveraging increasingly powerful observational tools, astronomers are ensuring that when we finally answer that question, we'll have searched as thoroughly and thoughtfully as possible.