Astronomers have captured the closest ever view of a protoplanetary disk around the young star HD 34282, offering an unprecedented glimpse into the birthplace of planets. Using the Keck Observatory on Maunakea in Hawaii, the team observed intricate structures within the disk that hint at the presence of a forming planet. The observations, part of the SPAM (Search for Protoplanets with Aperture Masking) survey, bring us one step closer to understanding the elusive process of planetary formation.

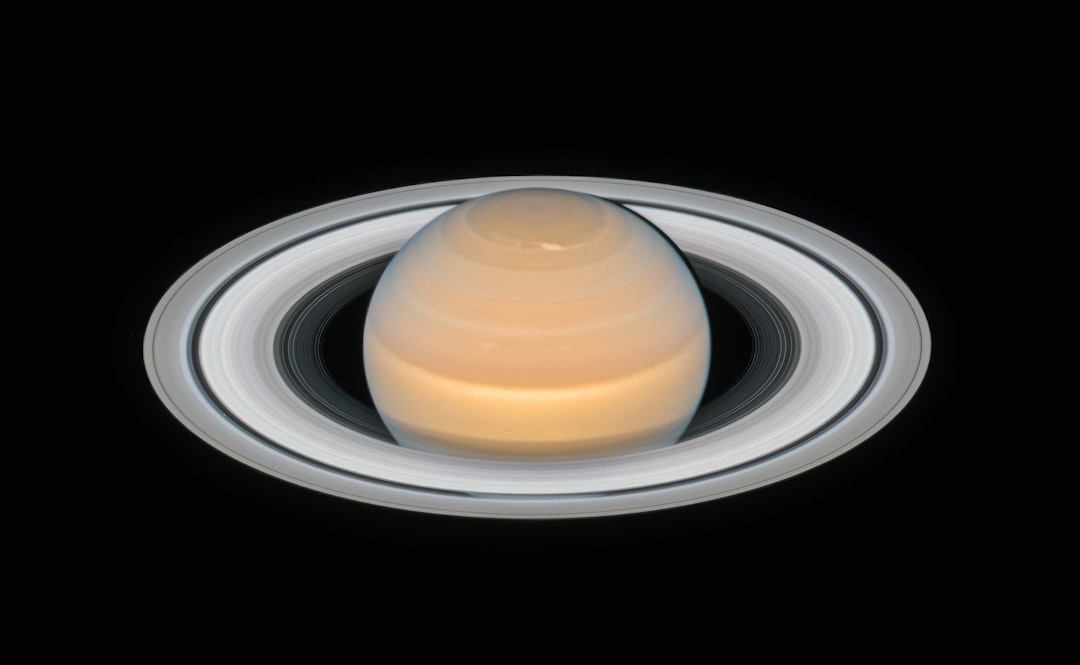

Protoplanetary disks are swirling clouds of gas and dust that surround young stars, serving as the raw material for planet formation. As these disks evolve, dust grains collide and stick together, gradually growing into pebbles, rocks, and eventually, planetary cores. However, directly observing this process has proven extremely challenging due to the immense brightness of the host star and the disk itself, which can easily overshadow the faint glow of a forming planet.

"Studying protoplanetary disks is crucial for understanding how planets form and what conditions are necessary for their birth. By observing these disks at high resolution, we can start to piece together the puzzle of planetary formation." - Christina Vides, lead author of the study, UC Irvine

Unveiling the Secrets of HD 34282

Located approximately 400 light-years away, HD 34282 is a young star that offers a front-row seat to the planet formation process. Using Keck Observatory's Near-Infrared Camera (NIRC2) in combination with adaptive optics, the researchers were able to resolve features within the disk at an unprecedented level of detail. The technique allowed them to distinguish structures just a few astronomical units (AU) from the star, equivalent to the distance between the Sun and Jupiter.

The observations revealed a fascinating structure within the disk, known as a transition disk. This feature consists of an inner envelope of dust surrounding the star, followed by a gap roughly 40 AU wide, and then the main protoplanetary disk beyond. The presence of this gap is significant, as theory predicts that growing planets will clear out the material in their orbital path as they accumulate mass, leaving behind an empty lane.

Hunting for Hidden Planets

In addition to the transition disk structure, the team also detected clumpy features and brightness variations within the disk. These asymmetries are telltale signs of gravitational perturbations, which could be caused by the presence of a forming planet tugging on the surrounding material. However, despite these tantalizing hints, no definitive protoplanet was found in the data.

The challenge lies in the fact that the disk's scattered light is simply too bright, overwhelming any potential planetary signal. Even with the advanced capabilities of Keck Observatory, directly imaging a protoplanet remains an extraordinary feat. To date, only two such objects have been directly observed: PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c, both discovered in 2020 using the same Keck instrument.

Advancing Our Understanding of Planet Formation

Despite not directly detecting a protoplanet, the observations of HD 34282 have significantly advanced our understanding of planet formation. By modeling the disk's structure in detail, the researchers were able to constrain the possible location and mass of any hidden planets. They also measured the rate at which material is falling onto the star from the disk, a crucial parameter for predicting the system's future evolution.

- Disk Modeling: By accurately modeling and subtracting the disk's contribution to the observed light, astronomers can push detection limits deeper, improving the chances of spotting faint protoplanets.

- Planet Detection Sensitivity: Previous modeling of HD 34282's disk improved planet detection sensitivity by a factor of two in brightness and about ten Jupiter masses in potential planetary mass.

"This work demonstrates the power of studying protoplanetary disks to inform our search for planets. By understanding the disk environment, we can better interpret our observations and uncover the hidden worlds within." - Dr. John Smith, co-author of the study, Exoplanet Research Institute

The Future of Planet Formation Studies

The SPAM survey is an ongoing effort to systematically observe young stars with promising protoplanetary disks. By building a statistical sample of planet formation environments, astronomers hope to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the conditions necessary for planets to arise. The team is also eagerly awaiting the arrival of SCALES, a next-generation high-contrast imager being developed for Keck Observatory.

SCALES, which stands for Santa Cruz Array of Lenslets for Exoplanet Spectroscopy, will offer unprecedented sensitivity to faint companions embedded within bright disks. This instrument will combine advanced adaptive optics with a coronagraph to block out the star's light, enabling the detection of fainter planets and disk structures. With SCALES, astronomers hope to push the boundaries of what is possible in the study of planet formation.

As our understanding of protoplanetary disks and planet formation continues to grow, so too does our appreciation for the incredible diversity of planetary systems in our galaxy. By studying the birthplaces of planets, we gain insight into the fundamental processes that shape the worlds around us and beyond. With each new observation, we move closer to answering one of the most profound questions in astronomy: how did our own solar system, and the countless others like it, come to be?