The fragile orbital infrastructure surrounding our planet is far more precarious than most people realize. In a groundbreaking analysis that should serve as a wake-up call to space agencies and satellite operators worldwide, researchers have quantified just how close we are to a catastrophic cascade of collisions in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). The findings are sobering: if satellite operators were to lose control of their spacecraft today, we would have approximately 2.8 days before a devastating collision occurs—a dramatic reduction from the 121 days of safety margin that existed just seven years ago.

This alarming assessment comes from Dr. Sarah Thiele, a researcher who began this work as a PhD student at the University of British Columbia and is now continuing her research at Princeton University. Along with her co-authors, Thiele has published a comprehensive analysis available in pre-print on arXiv that describes our current satellite mega-constellation system as an unstable "house of cards"—a metaphor that captures the precarious balance of thousands of spacecraft hurtling through space at speeds exceeding 17,000 miles per hour.

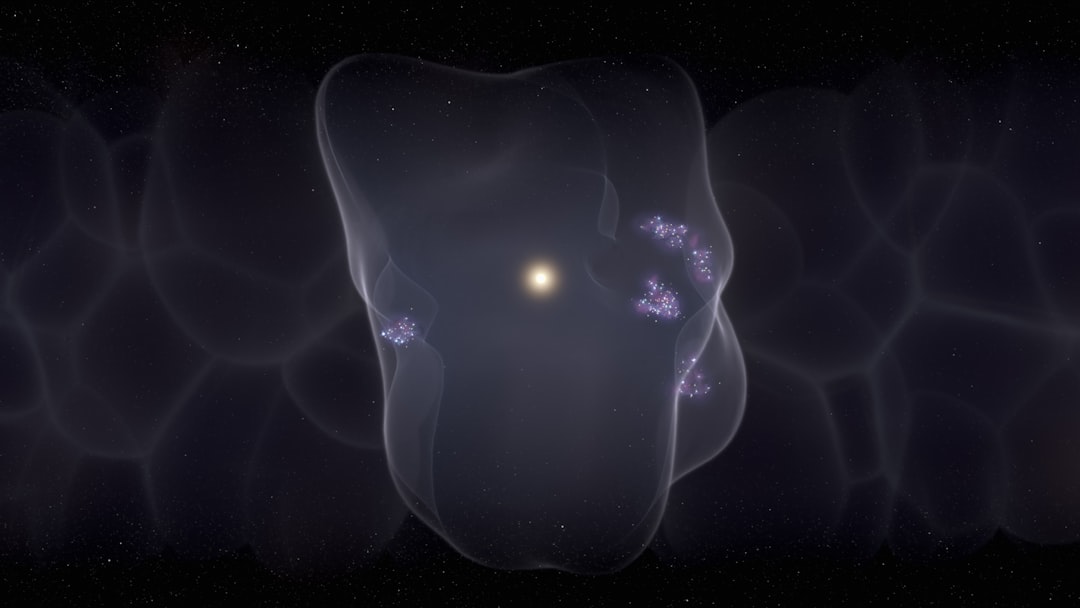

The proliferation of mega-constellations, particularly SpaceX's Starlink network, has fundamentally transformed the orbital environment. What was once a relatively sparse collection of satellites has become a densely populated region where close encounters occur with alarming frequency. The implications extend far beyond the immediate threat to individual satellites—we're potentially facing a scenario that could render space access impossible for generations to come.

The Crowded Highway of Low Earth Orbit

To comprehend the severity of the situation, consider these staggering statistics: across all LEO mega-constellations currently in operation, a "close approach"—defined as two satellites passing within one kilometer of each other—occurs every 22 seconds. For context, one kilometer might seem like a comfortable distance on Earth, but in the high-speed environment of orbital mechanics, it represents a dangerously narrow margin for error. When focusing exclusively on the Starlink constellation, which now comprises thousands of active satellites, this frequency increases to one close approach every 11 minutes.

These aren't theoretical calculations divorced from operational reality. Each Starlink satellite performs an average of 41 collision-avoidance maneuvers per year. While this might initially appear to demonstrate an efficiently managed system operating as designed, experienced systems engineers recognize a troubling pattern. The constant need for intervention suggests the system is operating at the edge of its safety margins, leaving little room for unexpected complications or what engineers call "edge cases"—those rare but consequential events that can push a system beyond its designed tolerances.

The NASA Orbital Debris Program Office has been tracking this escalating concern for years, but the rapid deployment of mega-constellations has outpaced many predictive models. The orbital environment has become exponentially more complex in a remarkably short timeframe, creating unprecedented challenges for space traffic management.

Solar Storms: The Hidden Threat Multiplier

Among the various edge cases that could trigger a catastrophic cascade, solar storms represent perhaps the most insidious threat. These powerful eruptions from our Sun don't simply pose a direct danger to satellite electronics—they fundamentally alter the orbital environment in ways that compound existing risks. The research team identified two primary mechanisms through which solar storms threaten satellite mega-constellations, each capable of triggering a chain reaction of collisions.

Atmospheric Heating and Orbital Uncertainty

The first mechanism involves the heating of Earth's upper atmosphere. When a solar storm strikes, the influx of energetic particles causes the thermosphere to expand and heat up dramatically. This expansion increases atmospheric drag on satellites, forcing them to expend precious fuel reserves to maintain their designated orbits. Simultaneously, this atmospheric perturbation introduces significant positional uncertainty—operators can no longer predict satellite locations with the precision required for safe operations.

The May 2024 "Gannon Storm" provided a sobering real-world demonstration of this phenomenon. During this event, which represented one of the strongest solar storms in recent decades, more than half of all satellites in LEO were forced to perform emergency repositioning maneuvers. The fuel expenditure was substantial, and for satellites already nearing the end of their operational lives, such events can precipitate premature deorbiting or, worse, create uncontrolled debris.

Communications Blackout Scenario

The second and potentially more catastrophic mechanism involves the disruption of satellite navigation and communications systems. Solar storms can overwhelm spacecraft electronics, rendering satellites unable to receive commands or execute evasive maneuvers. When combined with the increased drag and positional uncertainty caused by atmospheric heating, this creates a perfect storm scenario where satellites become uncontrollable objects drifting through an already crowded and destabilized orbital environment.

"The combination of increased atmospheric drag, positional uncertainty, and potential loss of satellite control creates a scenario where the carefully choreographed dance of orbital mechanics breaks down completely. We're essentially flying blind through a traffic jam," explains Dr. Thiele in discussing the research implications.

Introducing the CRASH Clock: A New Metric for Orbital Catastrophe

While the Kessler Syndrome—named after NASA scientist Donald Kessler who first described it in 1978—has long been recognized as the ultimate orbital catastrophe scenario, it represents a slow-motion disaster that unfolds over decades. The Kessler Syndrome describes a cascade effect where one collision creates debris that triggers additional collisions, eventually creating a self-sustaining cloud of debris that makes certain orbital regions unusable. However, this gradual progression doesn't capture the immediate danger posed by solar storm-induced control loss.

To address this gap, Thiele and her colleagues developed a new metric they call the Collision Realization and Significant Harm (CRASH) Clock. This measurement quantifies how quickly a catastrophic collision would occur if satellite operators simultaneously lost the ability to command their spacecraft. The results are deeply concerning and represent a fundamental shift in orbital risk assessment.

According to their calculations, as of June 2025, the CRASH Clock stands at approximately 2.8 days. This means that if all satellite operators were to lose control simultaneously—a scenario entirely plausible during a severe solar storm—we would have less than three days before a collision occurs that could seed the beginning of Kessler Syndrome. To appreciate how dramatically the situation has deteriorated, consider that in 2018, before the mega-constellation era truly began, the same calculation yielded a result of 121 days.

The research reveals an even more alarming statistic: if operators lose control for just 24 hours, there exists a 30% probability of a catastrophic collision. This isn't a remote, theoretical risk—it's a coin flip with humanity's access to space hanging in the balance. The European Space Agency's Space Debris Office has independently corroborated concerns about the rapidly deteriorating orbital environment, though the CRASH Clock metric provides a new framework for understanding the immediacy of the threat.

Historical Precedent: The Carrington Event and Modern Vulnerability

The threat of a civilization-altering solar storm isn't mere speculation—we have historical precedent. The Carrington Event of 1859, named after British astronomer Richard Carrington who observed the solar flare, remains the most powerful solar storm in recorded history. The geomagnetic disturbances were so intense that telegraph systems across Europe and North America failed, with some operators receiving electric shocks and telegraph paper catching fire from induced currents.

If a Carrington-class event were to occur today, the consequences would be exponentially more severe. Modern technological infrastructure, including the satellite networks we depend upon for communications, navigation, weather forecasting, and countless other services, would face disruption far exceeding the 2.8-day threshold calculated by the CRASH Clock. The loss of satellite control could extend for weeks, virtually guaranteeing multiple catastrophic collisions and potentially triggering the full cascade of Kessler Syndrome.

The 2024 Gannon Storm, while severe, was significantly weaker than the Carrington Event, yet it still forced emergency responses across the satellite industry. Scientists at NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center estimate that a Carrington-class event has approximately a 10-12% probability of occurring within any given decade—not a question of if, but when.

The Warning Time Problem and Real-Time Control Requirements

Compounding the challenge is the limited warning time available for solar storms. Current space weather monitoring systems, including NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory and NOAA's DSCOVR satellite, can typically provide between one to two days of advance notice for major solar storms. While this might seem adequate, it's barely sufficient given the complex coordination required to safeguard thousands of satellites simultaneously.

The dynamic nature of solar storm effects on the atmosphere necessitates real-time feedback and control to effectively manage satellite constellations. Operators must continuously adjust orbits based on current atmospheric conditions, collision probabilities, and the status of neighboring spacecraft. This requires not just functional satellites, but also intact ground control infrastructure and communication links—all of which are vulnerable to the same solar storm effects threatening the satellites themselves.

The research team emphasizes that pre-positioning satellites before a storm, while helpful, cannot fully mitigate the risk. The atmospheric effects are too dynamic, and the duration of impact too uncertain. Once real-time control is lost, the CRASH Clock begins its countdown, and there may be little humanity can do except watch and hope.

Implications and the Path Forward

The implications of this research extend far beyond academic interest—they represent a fundamental challenge to humanity's relationship with space. The benefits of mega-constellations are undeniable: global internet coverage, improved Earth observation, enhanced communications capabilities, and economic opportunities. However, these benefits must be weighed against the existential risk to space access itself.

Several potential mitigation strategies warrant serious consideration:

- Enhanced Space Weather Forecasting: Investment in improved solar monitoring systems could extend warning times, though this addresses only part of the problem. Organizations like ESA's Space Weather Service Network are working to improve predictive capabilities.

- Satellite Hardening: Designing spacecraft with greater resilience to solar storm effects, including redundant systems and radiation-hardened electronics, could maintain control during events that would disable current satellites.

- Active Debris Removal: Developing and deploying systems capable of removing defunct satellites and debris could reduce the baseline collision risk, providing greater safety margins.

- International Coordination: Establishing robust international frameworks for space traffic management and emergency protocols could improve collective response capabilities during solar storm events.

- Orbital Altitude Diversification: Spreading satellite networks across a broader range of altitudes could reduce the concentration of spacecraft in any single orbital shell, decreasing collision probabilities.

The paper makes clear that we're making decisions about orbital infrastructure with incomplete understanding of the risks involved. The CRASH Clock provides a quantitative framework for these discussions, moving the debate from abstract concerns about future debris to concrete timelines for potential catastrophe. When the margin between normal operations and disaster is measured in days rather than years, the urgency of addressing these challenges becomes undeniable.

A Critical Juncture for Space Access

Humanity stands at a critical juncture in its relationship with the space environment. The same technological capabilities that enable global connectivity through mega-constellations also create vulnerabilities that could close the door to space for generations. A single severe solar storm—an event we know has occurred before and will occur again—could trigger a cascade of collisions that renders Low Earth Orbit unusable for decades or longer.

The 2.8-day CRASH Clock isn't a prediction of inevitable doom, but rather a warning signal that demands attention. It quantifies the fragility of our current orbital infrastructure and highlights the need for informed decision-making about how we utilize and manage space. The house of cards metaphor is apt: we've built an impressive structure, but it's fundamentally unstable, vulnerable to a strong wind that we know is coming.

As Dr. Thiele and her colleagues conclude, the trade-offs between utilizing LEO mega-constellations' technical capabilities and the risks they pose to future space endeavors must be carefully considered. The benefits are real and significant, but so are the dangers. With realistic risk assessment now available through metrics like the CRASH Clock, the space industry, regulatory bodies, and society at large can make informed decisions about how to proceed. The question is whether we'll act on this information before the house of cards collapses, or whether we'll learn this lesson the hard way, watching helplessly as our access to space disappears in a cascade of collisions that could have been prevented.