The story of our universe's evolution represents one of humanity's most profound intellectual achievements—a narrative that bridges the gap between scientific theory and mythological storytelling. In this fourth installment of our series examining the Big Bang's mythic dimensions, we explore how the cosmos transformed from a nearly featureless expanse into the intricate cosmic web we observe today, complete with galaxies, stars, and the vast voids between them. This transformation, driven by the relentless force of gravity acting over hundreds of millions of years, reveals striking parallels between modern cosmology and ancient creation narratives.

Following the formation of the first protons, neutrons, and light elements in the universe's earliest moments, the cosmos entered what cosmologists call the "Dark Ages"—a period lasting several hundred thousand years when the universe expanded and cooled without dramatic structural changes. During this epoch, documented extensively by research from NASA's Planck mission, the universe consisted primarily of an almost perfectly uniform hot plasma that gradually transitioned into neutral gas as temperatures dropped below 3,000 Kelvin.

Yet beneath this apparent uniformity, the seeds of all future cosmic structure were already present—tiny density fluctuations, no larger than one part in 100,000, that would ultimately give rise to everything we see in the universe today.

The Hidden Blueprint: Quantum Fluctuations Become Cosmic Architecture

The remarkable uniformity of the early universe, paradoxically, contained the blueprint for all future complexity. These minute density variations, originating from quantum fluctuations during the inflationary epoch, were preserved and amplified as the universe expanded. Modern observations from the European Space Agency's Planck satellite have mapped these primordial fluctuations with extraordinary precision, revealing the cosmic microwave background radiation's subtle temperature variations that correspond directly to these density differences.

These infinitesimal irregularities—regions where matter was compressed ever so slightly more densely than their surroundings—possessed marginally stronger gravitational fields. While the difference was minuscule, gravity is a patient force. Over millions of years, these slightly denser regions began to attract surrounding matter, growing incrementally larger and denser. As physicist and cosmologist Sean Carroll has noted, this process represents one of nature's most elegant feedback mechanisms: density begets gravity, gravity begets more density, and the cycle continues in an accelerating cascade.

Gravity's Patient Architecture: Building Structure Over Cosmic Time

The process of gravitational collapse occurred with agonizing slowness by human standards, yet with remarkable speed on cosmic timescales. During the first hundred million years after the Big Bang, these density perturbations grew through a process called hierarchical structure formation. Smaller clumps merged to form larger ones, which in turn combined to create even more massive structures. This "bottom-up" assembly process, predicted by cold dark matter theory and confirmed by observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, continues to shape our universe today.

As these primordial clouds of hydrogen and helium gas contracted under their own gravity, their cores became increasingly dense and hot. When the temperature and pressure at the center of these collapsing clouds reached approximately 10 million degrees Kelvin, a threshold was crossed: hydrogen nuclei began fusing into helium, releasing tremendous amounts of energy. The universe's first stars—known to astronomers as Population III stars—ignited, ending the cosmic Dark Ages and ushering in the epoch of reionization.

"The formation of the first stars represents one of the most significant phase transitions in cosmic history. These massive, metal-free stars fundamentally altered the chemistry and structure of the universe, seeding it with the heavy elements necessary for planets and life," explains Dr. Abraham Loeb, former chair of Harvard's astronomy department.

From Stars to Galaxies: The Emergence of Cosmic Cities

Individual stars did not exist in isolation. Gravity continued its work on larger scales, gathering stars into groups and clusters. These stellar assemblages, bound together by their mutual gravitational attraction, formed the first protogalaxies—the ancestors of modern galaxies like our Milky Way. Recent observations suggest that the earliest galaxies formed remarkably quickly, within the first 400-500 million years after the Big Bang, challenging previous theoretical models that predicted a more gradual assembly process.

These primordial galaxies were quite different from the majestic spiral and elliptical galaxies we observe today. They were smaller, more irregular, and underwent violent episodes of star formation at rates far exceeding anything seen in the modern universe. As these protogalaxies consumed surrounding gas and merged with one another, they grew progressively larger. The most massive galaxies resided in the densest regions of the universe, where multiple galaxies could come together to form galaxy clusters—gravitationally bound systems containing hundreds or thousands of individual galaxies.

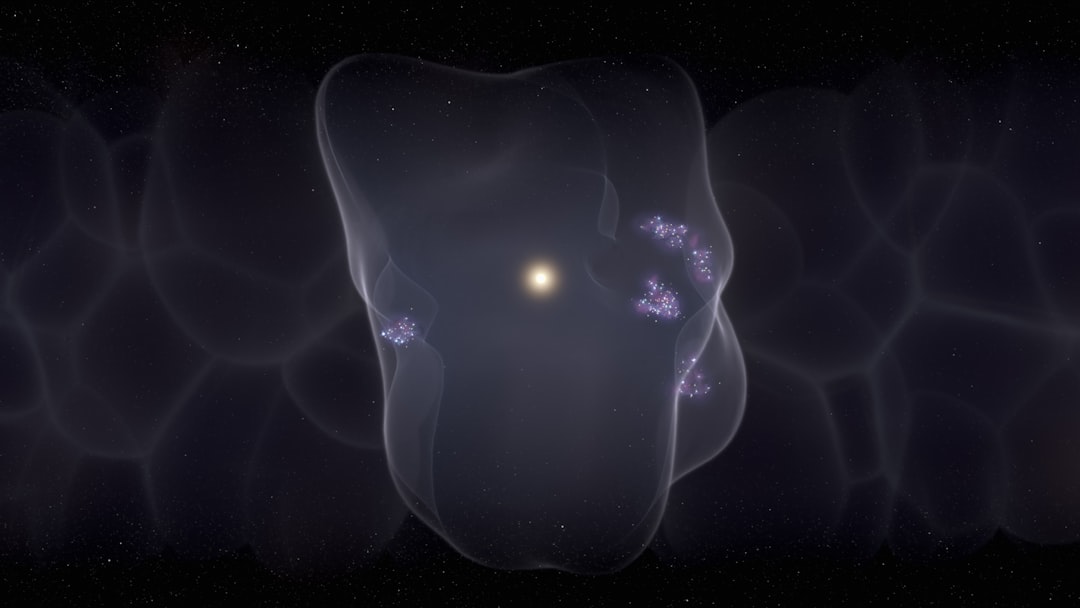

The Cosmic Web: Nature's Grandest Pattern

Within approximately 500 million to one billion years after the Big Bang, the large-scale structure of the universe had assumed a distinctive pattern that astronomers call the cosmic web. This three-dimensional network consists of several key components, each playing a crucial role in the universe's architecture:

- Galaxy clusters: The densest nodes in the cosmic web, containing hundreds to thousands of galaxies bound together by gravity, with masses reaching up to a quadrillion times that of our Sun

- Filaments: Thread-like structures stretching across tens to hundreds of millions of light-years, containing chains of galaxies and serving as the cosmic web's "highways" for matter transport

- Walls or sheets: Two-dimensional surfaces where filaments intersect, forming vast planes of galaxies that can span hundreds of millions of light-years

- Cosmic voids: Enormous regions of near-emptiness, typically 100-400 million light-years across, containing very few galaxies and representing the spaces from which matter was gravitationally evacuated

This cosmic web structure, mapped in detail by surveys such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, represents the largest coherent pattern found in nature. The voids are particularly significant—they are not simply empty space that existed before, but rather regions that were actively hollowed out as gravity drew matter away to build the filaments, walls, and clusters. In essence, the cosmic web's bright features exist because of the dark, empty voids, and vice versa.

Scientific Theory Meets Mythological Structure: The Big Bang as Modern Creation Story

The narrative arc of Big Bang cosmology—from the mysterious singularity through the separation of fundamental forces, the creation of matter and light, to the emergence of cosmic structure—bears remarkable structural similarities to creation myths found across human cultures. This parallel is not coincidental but reflects deep patterns in how humans construct explanatory narratives about origins and existence.

Consider the key mythological elements present in the Big Bang narrative: creation ex nihilo (the singularity appearing without prior cause), the separation of a unified whole into distinct parts (the breaking of symmetry as forces split), primordial chaos giving way to order (the transition from uniform plasma to structured matter), and the emergence of the world from formless void (gravity sculpting the cosmic web from featureless gas). These are themes that echo through creation stories from ancient Mesopotamia to Indigenous Australian Dreamtime narratives.

The Human Element in Scientific Cosmology

The fact that Big Bang theory was first proposed by Georges Lemaître, a Belgian Catholic priest and physicist, in 1927 adds another layer to this discussion. Lemaître's dual identity as both scientist and theologian did not compromise the scientific rigor of his work—his theory was based on Einstein's general relativity and astronomical observations. However, it does highlight that scientists, like all humans, operate within cultural contexts that shape how they frame questions and construct explanations.

Contemporary anthropologists and philosophers of science, including those studying the sociology of scientific knowledge, argue that myths should not be dismissed as mere superstition but understood as proto-scientific theories—attempts to explain observed phenomena using the conceptual tools available within a given cultural framework. Myths respond to evidence (seasonal changes, celestial movements, natural phenomena) and provide coherent narratives that make sense of that evidence.

"Scientific theories and mythological narratives both serve to make the universe comprehensible to human minds. The difference lies not in the impulse to explain, but in the methodological tools employed—mathematics, empirical testing, and logical consistency for science; metaphor, symbolism, and cultural resonance for myth," notes anthropologist Dr. Claude Lévi-Strauss in his structural analysis of mythology.

The Unfinished Story: Future Chapters in Cosmic Understanding

Despite the impressive explanatory power of Big Bang cosmology, significant mysteries remain. The nature of dark matter, which comprises approximately 85% of all matter in the universe and played a crucial role in structure formation, remains unknown. The even more mysterious dark energy, driving the universe's accelerating expansion, defies easy explanation within current physical frameworks. And the singularity itself—that point of infinite density at time zero—represents a breakdown of our physical theories, suggesting that our creation story is incomplete.

Future observations from next-generation instruments, including the ESA's Euclid mission and ground-based facilities like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, will undoubtedly refine and perhaps revolutionize our understanding of cosmic evolution. These missions will map the cosmic web in unprecedented detail, probe the nature of dark energy, and potentially reveal new physics beyond our current Standard Model.

The Big Bang theory represents humanity's current best answer to the age-old question: "Where did everything come from?" It is a story constructed using the rigorous tools of science—mathematics, observation, and empirical testing—yet it follows narrative patterns deeply embedded in human culture. Whether we call it a scientific theory or a modern creation myth, it serves the same fundamental purpose: helping us understand our place in the vast cosmos and explaining how the universe came to be as we find it today. As our observational capabilities expand and our theoretical understanding deepens, this story will continue to evolve, just as creation narratives have evolved throughout human history, adapting to new evidence while maintaining their essential function of making the universe comprehensible to human minds.

The cosmic web we observe today—with its clusters, filaments, and voids spanning billions of light-years—stands as a testament to gravity's patient work over cosmic time. From nearly perfect uniformity emerged the rich complexity of structure we see around us, a transformation that took hundreds of millions of years but whose effects will persist for trillions of years to come. In this sense, we are still living in the aftermath of the Big Bang, still watching its story unfold, still participants in the grandest narrative ever conceived.