The quest to detect exomoons—natural satellites orbiting planets beyond our solar system—represents one of astronomy's most tantalizing challenges. When the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launched in December 2021, the scientific community eagerly anticipated that its unprecedented infrared capabilities would finally reveal these elusive worlds. Yet after more than four years of revolutionary observations that have transformed our understanding of the cosmos, JWST has still not definitively confirmed a single exomoon. A groundbreaking new study led by Dr. David Kipping of Columbia University reveals exactly why this detection remains so extraordinarily difficult, even with humanity's most powerful space observatory.

The research team invested an exceptional 60 hours of JWST observation time—an enormous allocation given the telescope's overwhelming demand—to study Kepler-167e, a Jupiter-like exoplanet that seemed like an ideal candidate for hosting detectable moons. Despite this massive observational effort using JWST's sophisticated NIRSpec instrument and applying multiple advanced data analysis techniques, the team could not definitively confirm the existence of an exomoon. Instead, they discovered that what initially appeared to be a promising exomoon signal was most likely caused by something far more mundane: a starspot on the host star's surface.

This study, available as a pre-print on arXiv, provides crucial insights into the formidable technical and analytical challenges that astronomers face when attempting to detect these distant moons. The findings underscore why exomoon detection remains at the cutting edge of observational astronomy, requiring not just powerful instruments but also sophisticated data processing, rigorous model testing, and careful consideration of alternative explanations.

The Elusive Nature of Exomoon Detection

Understanding why exomoons are so difficult to detect requires appreciating the extraordinary challenges of observing planetary systems light-years away. When astronomers detect exoplanets using the transit method, they measure the tiny dip in a star's brightness as a planet passes in front of it. For a Jupiter-sized planet transiting a Sun-like star, this brightness decrease is typically less than 1%. An exomoon would create an even smaller signal—potentially just a fraction of the planet's already minuscule effect.

The situation becomes even more complex when considering the dynamics of moon orbits. Unlike planets, which follow relatively predictable paths around their stars, exomoons orbit their host planets, creating variable timing patterns in transit observations. This means the moon's position relative to the planet changes with each transit, producing different light curve signatures. As Dr. Kipping explains in his Cool Worlds YouTube channel, this variability makes it extremely challenging to distinguish genuine exomoon signals from instrumental noise or stellar activity.

Previous Exomoon Candidates: Promising but Unconfirmed

JWST has identified two intriguing potential exomoon candidates, though both remain unconfirmed and rely on indirect evidence rather than direct detection. The first involves WASP-39b, a "hot Saturn" exoplanet that exhibits significant variability in its atmospheric sodium and sulfur dioxide concentrations. Researchers analyzing this system have proposed that an extremely volcanic, tidally heated exomoon could be ejecting gases that subsequently interact with the planet's atmosphere. This scenario draws parallels to Jupiter's moon Io, the most volcanically active body in our solar system, which experiences intense tidal heating due to Jupiter's gravitational pull.

The second candidate involves W1935, a brown dwarf—a substellar object too massive to be a planet but not massive enough to sustain hydrogen fusion like a true star. This object displays unexplained methane emissions in its atmosphere that don't fit standard models of brown dwarf chemistry. One possible explanation is that an undiscovered exomoon with active geological processes could be supplying this methane. However, like the WASP-39b case, this remains speculative, based on atmospheric anomalies rather than direct observation of a moon.

These cases illustrate a fundamental challenge in exomoon science: distinguishing between phenomena that could be explained by an exomoon versus other astrophysical processes. Without direct detection, astronomers must carefully evaluate whether exotic explanations involving moons are truly necessary or if more conventional mechanisms can account for the observations.

Why Kepler-167e Seemed Like the Perfect Target

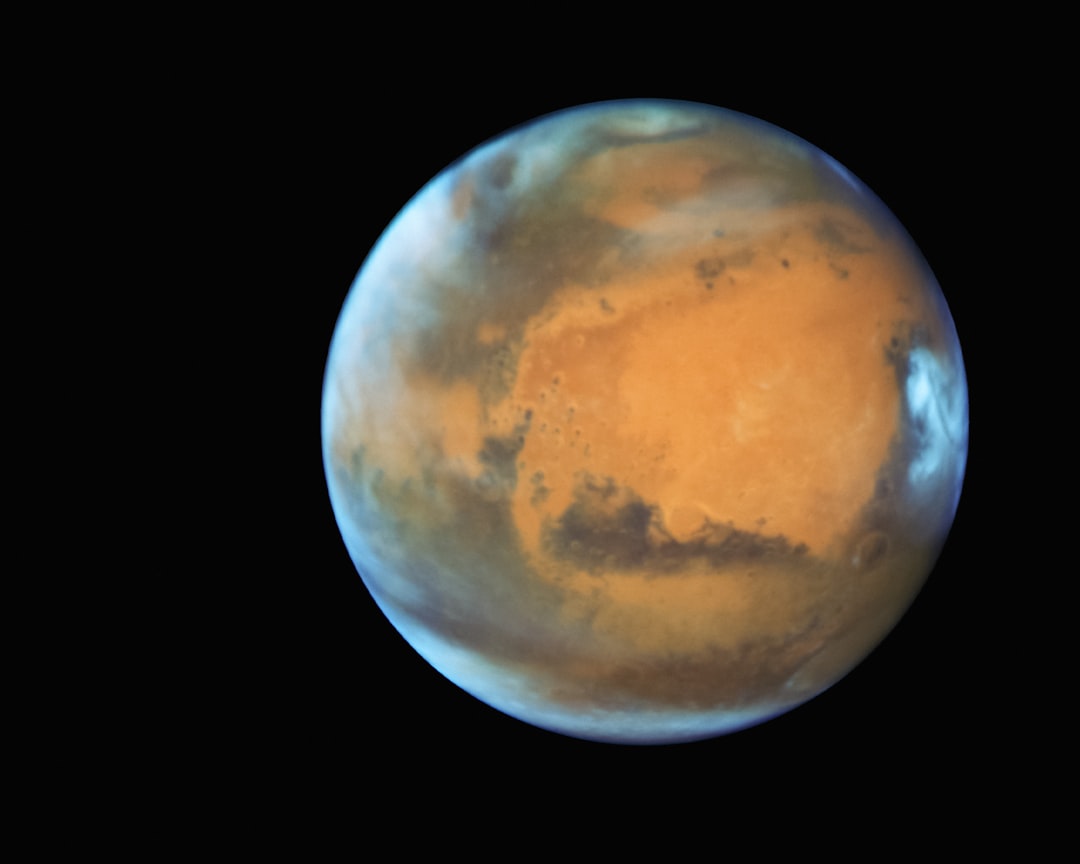

Kepler-167e emerged as an exceptionally promising candidate for exomoon detection for several compelling reasons. Located approximately 1,119 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus, this exoplanet ranks among the closest analogues to Jupiter yet discovered. With a mass of 0.91 Jupiter masses and an orbital distance of 1.88 astronomical units (AU)—positioned between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter in our own solar system—Kepler-167e occupies what astronomers call the "habitable zone" for moons.

The logic behind targeting this world is straightforward: Jupiter hosts more than 70 confirmed moons, including Ganymede, which at 5,268 kilometers in diameter is the largest moon in our solar system—even bigger than the planet Mercury. If a Jupiter-like exoplanet formed through similar processes and experienced comparable dynamical history, it stands to reason that it too should possess a substantial moon system. According to NASA's planetary science research, the formation of large moons around gas giants is a natural outcome of planet formation processes, making Kepler-167e an excellent test case.

The Kepler-167 system also contains three additional "Super-Earth" exoplanets, which added complexity to the analysis. These planets needed to be carefully accounted for as confounding factors in the light curves, as their gravitational influences could potentially affect the timing and appearance of Kepler-167e's transits. This multi-planet architecture required sophisticated modeling to ensure that any detected signals were truly attributable to a moon rather than planetary interactions.

The Intensive Observational Campaign and Data Analysis

The research team's allocation of 60 hours of JWST observation time represents an extraordinary commitment of resources. To put this in perspective, JWST receives thousands of observing proposals each cycle, with typical allocations measured in just a few hours. The observations were strategically divided into six separate 10-hour segments, with brief intervals between each block to allow for telescope operations and data downlink.

During these observations, the team encountered an unexpected technical challenge. Over each 10-hour observational window, they noticed that the intensity of the light curves would gradually decrease—a phenomenon they attributed to "detector effects" in the NIRSpec instrument. Critically, this instrumental drift occurred on a similar timescale to the expected signal from an exomoon transit, making it extremely difficult to distinguish between a genuine astronomical phenomenon and an artifact of the detector's behavior.

"The detector effects we observed operate on the same timescales as potential exomoon signals, creating a significant challenge in data interpretation. This highlights why exomoon detection requires not just powerful telescopes, but also sophisticated data analysis techniques to separate real signals from instrumental artifacts."

To address these challenges and minimize potential biases, the researchers employed a rigorous multi-pipeline approach to data analysis. They developed a custom pipeline specifically designed for this observational campaign, while also processing the data through two established pipelines: ExoTiC-JEDI and katahdin. Each pipeline applies different algorithms for removing instrumental effects, correcting for systematic errors, and extracting the underlying astronomical signal.

Advanced Statistical Modeling Techniques

The processed data from each pipeline was then compared against four distinct statistical models, ranging in mathematical complexity:

- Simple Quadratic Fit: A basic polynomial model that assumes smooth, predictable variations in the light curve

- Gaussian Process with Matérn-3/2 Kernel: An advanced statistical technique that can capture complex, non-periodic variations in the data without assuming a specific functional form

- Intermediate Models: Two additional approaches that balanced computational efficiency with modeling flexibility

This comprehensive approach generated twelve different combinations of data pipelines and statistical models. Remarkably, seven of these twelve combinations indicated the presence of a possible exomoon in the JWST data. However, as any experienced astronomer knows, detecting a signal is only the first step—ruling out alternative explanations is equally crucial for confirming a discovery.

The Starspot Alternative: A More Likely Explanation

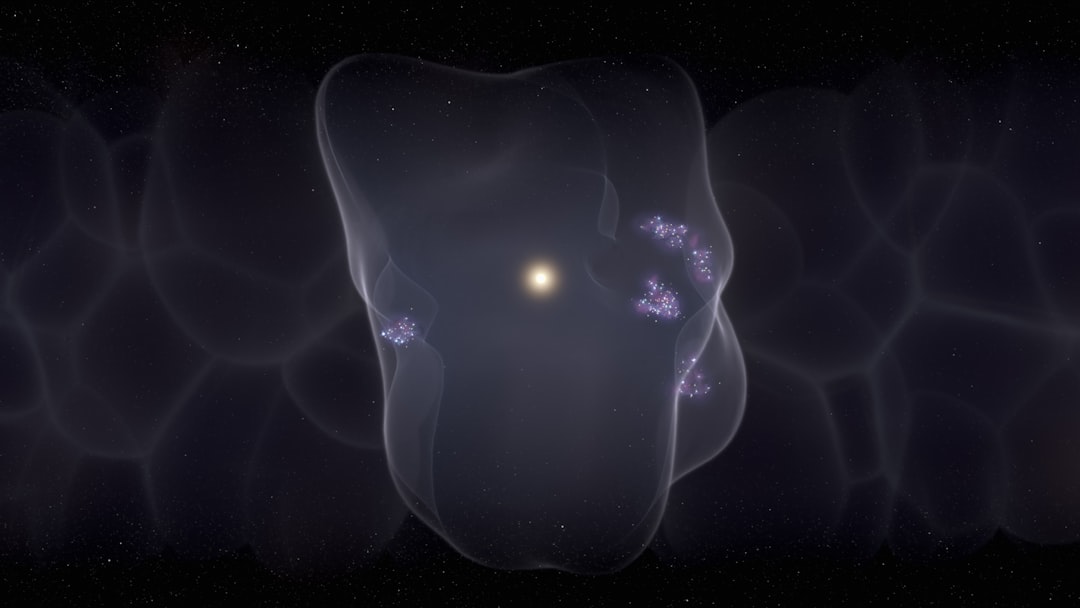

Upon closer examination, the research team identified a more prosaic explanation for their tantalizing signal: the planet may have transited across a starspot on Kepler-167's surface. Starspots are cooler, darker regions on a star's photosphere, analogous to sunspots on our Sun but potentially much larger. When a planet passes in front of a starspot during its transit, the overall brightness dip appears slightly different than expected, creating what's called a syzygy-like event—a configuration where the moon, planet, and star appear aligned, but the signal actually results from the planet-starspot interaction.

Several pieces of evidence supported this starspot interpretation. First, while Kepler-167 is generally described as "quiescent" in astronomical terminology—meaning it shows relatively low levels of stellar activity—previous observations from the Kepler Space Telescope and Spitzer Space Telescope indicated that the star does produce spots large enough to account for the observed light curve variations. According to research on stellar activity and exoplanet detection, even relatively quiet stars can produce starspots that complicate transit observations.

Second, when the team attempted to calculate the physical characteristics of the hypothetical moon based on the observed signal, they determined it would need to be 30% larger than theoretical models predict is possible for moon formation around gas giant planets. Current understanding of satellite formation, based on both observations of our solar system and theoretical modeling, suggests there are upper limits to how large moons can grow relative to their host planets. A moon exceeding these limits would challenge fundamental theories of planetary system formation.

Faced with these considerations—the possibility of starspot contamination and the implausibly large size required for the moon—the research team concluded that a starspot provided the most parsimonious explanation for their observations. This conclusion exemplifies the scientific principle of Occam's Razor: when multiple explanations exist for a phenomenon, the simplest one that requires the fewest assumptions is typically preferred.

Implications and Future Observational Strategies

While the team's inability to confirm an exomoon after such an intensive observational campaign might seem disappointing, the study provides invaluable insights for future exomoon searches. The research demonstrates the critical importance of accounting for stellar activity in exomoon detection efforts. Future observational campaigns will need to incorporate detailed characterization of host star properties, including starspot frequency, size, and evolution timescales.

The team has proposed a follow-up observational campaign scheduled for October 2027, when Kepler-167e will transit its star again. This future observation would benefit from the lessons learned in the current study, potentially employing different observational strategies to mitigate detector effects and better characterize stellar activity. However, given the intense competition for JWST observation time, approval for this additional campaign remains uncertain.

Nevertheless, the broader exomoon research community remains active and optimistic. Multiple dedicated exomoon observational programs are currently approved or planned for upcoming JWST observation cycles. The European Space Agency is also developing future missions that could contribute to exomoon detection efforts, including improved instruments for characterizing exoplanet systems.

The Road Ahead: When Will We Confirm the First Exomoon?

The search for exomoons represents a frontier in observational astronomy that pushes the boundaries of our technological capabilities and analytical techniques. Dr. Kipping's study provides a roadmap for future efforts, highlighting the need for:

- Extended Observation Campaigns: Multiple transits observed over several years to distinguish moon signals from stellar variability

- Multi-Instrument Approaches: Combining data from different instruments and telescopes to cross-validate detections

- Advanced Modeling: Continued development of sophisticated statistical techniques to extract faint signals from noisy data

- Stellar Characterization: Detailed understanding of host star properties to identify and correct for starspot contamination

The scientific process often involves negative results—findings that rule out hypotheses rather than confirm them. While the team didn't confirm an exomoon around Kepler-167e, they've significantly advanced our understanding of the challenges involved and the methodologies required for future success. As observational techniques continue to improve and data analysis methods become more sophisticated, the detection of the first confirmed exomoon appears to be a matter of when, not if.

If these distant moons do exist—and theoretical considerations strongly suggest they should—humanity's most advanced telescopes and brightest minds are now equipped with the knowledge and tools to find them. The journey may be long and filled with false starts, but each attempt brings us closer to finally confirming that moons orbit planets around distant stars, just as they do in our own cosmic neighborhood.