A team of researchers from the Harvard Center for Astrophysics has made a groundbreaking discovery that sheds new light on the motion and history of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), one of the Milky Way's nearest galactic neighbors. By studying the trajectories of three hypervelocity stars ejected from the LMC, Scott Lucchini and Jiwon Jesse Han have constrained the path the LMC took over the past few billion years and provided compelling evidence for the existence of a supermassive black hole at its center. This research, published in the Astrophysical Journal, represents a significant step forward in our understanding of galactic dynamics and the complex gravitational interactions between the Milky Way and its satellite galaxies.

The Mystery of the Large Magellanic Cloud's Motion

Tracking the motion of distant objects outside our galaxy is a challenging task due to the relative nature of motion. For decades, astronomers have debated the path the LMC took over the past few billion years as it orbited the Milky Way. The LMC, a satellite galaxy located approximately 163,000 light-years away, is believed to be gravitationally bound to the Milky Way. However, determining whether the LMC is on its first or second pass around our galaxy has proven difficult due to the complexities of galactic-level orbital mechanics and the influence of dark matter.

"Understanding the motion of the Large Magellanic Cloud is crucial for unraveling the evolutionary history of our galactic neighborhood," said lead author Scott Lucchini. "By studying the trajectories of hypervelocity stars, we can gain valuable insights into the LMC's past and the existence of a central supermassive black hole."

Hypervelocity Stars: Probes of Galactic Dynamics

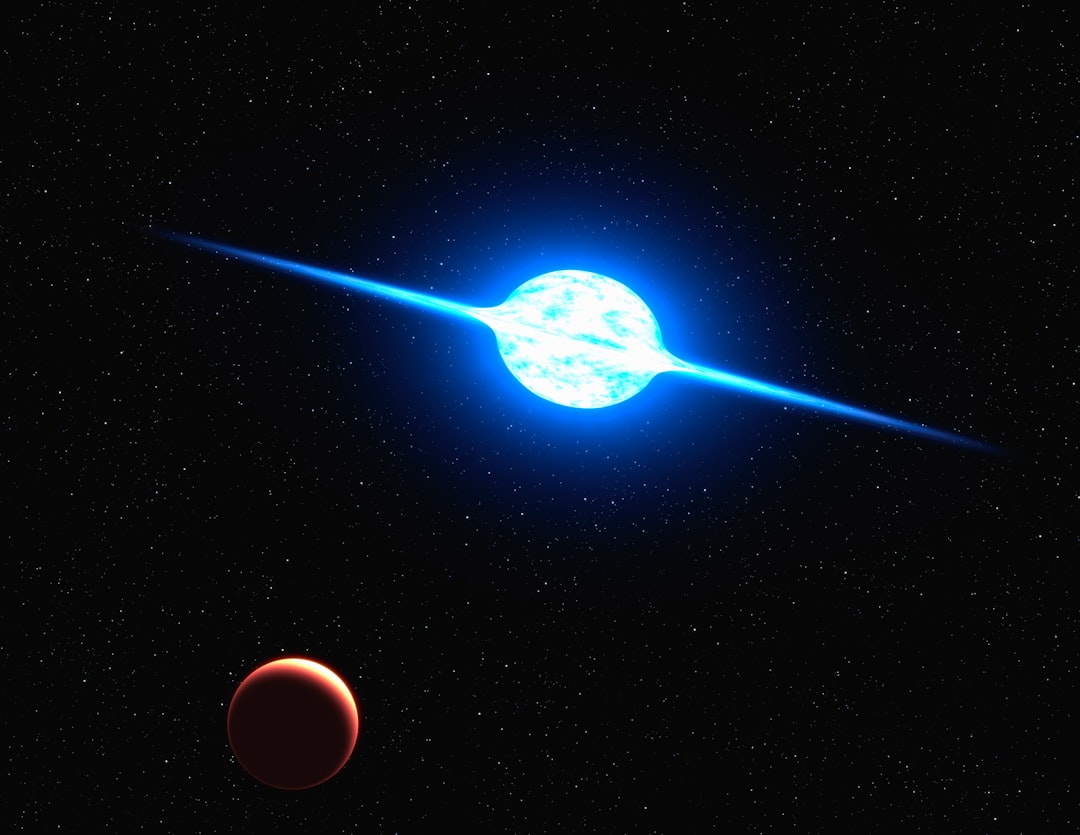

Hypervelocity stars are rare stellar objects that have been ejected from their binary systems at speeds exceeding 1,000 km/s, often due to close encounters with supermassive black holes. When a star" class="glossary-term-link" title="Learn more about Binary Star">binary star system ventures too close to a supermassive black hole, the intense tidal forces can disrupt the binary, capturing one star into orbit around the black hole while flinging the other out of the system at extreme velocities. These runaway stars eventually leave their host galaxy entirely, becoming isolated in the vast expanse between galaxies.

By tracing the trajectories of hypervelocity stars back to their origins, astronomers can pinpoint the location of the supermassive black holes responsible for their ejection. This technique has been used to study the Milky Way's central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*, and has now been applied to the LMC to shed light on its own central black hole and the galaxy's motion.

Discovering LMC Hypervelocity Stars

Lucchini and Han combed through the Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3), a comprehensive catalog of stellar positions and motions from the European Space Agency's Gaia mission, to identify hypervelocity stars that may have originated from the LMC. They discovered three promising candidates:

- HVS 3: A previously known hypervelocity star thought to have originated from the LMC.

- HVS 7 and HVS 15: Two newly discovered hypervelocity stars with trajectories indicating an LMC origin rather than the Milky Way.

The existence of these LMC hypervelocity stars provides compelling evidence for the presence of a supermassive black hole at the center of the LMC, a topic that has been debated among astronomers. While not a direct observation of the black hole itself, the discovery of LMC hypervelocity stars strengthens the case for its existence and narrows down its likely location.

Modeling the LMC's Motion and Dark Matter Influence

To accurately trace the LMC's path and account for the influence of dark matter, the researchers ran sophisticated simulations of the Milky Way and LMC's motion. They incorporated a component of "dynamical friction" to represent the drag experienced by the galaxies as they move through a field of smaller particles, primarily dark matter.

By combining these models with the trajectories of the three LMC hypervelocity stars, Lucchini and Han were able to constrain the "corridor" the LMC traveled through over the past few million years by an impressive 50%. However, the simulations could not definitively determine whether the LMC is on its first or second pass around the Milky Way.

"Our models are consistent with both First Passage and Second Passage scenarios for the LMC's orbit," explained co-author Jiwon Jesse Han. "Further observations and more robust modeling of the complex gravitational interactions between the Milky Way, LMC, and the surrounding dark matter will be necessary to resolve this question conclusively."

Pinpointing the LMC's Supermassive Black Hole

One of the study's key findings is the likely location of the LMC's central supermassive black hole. The researchers provide precise coordinates for the black hole, noting that it is offset by approximately 1.5 degrees from the visual center of the LMC. This offset is believed to be caused by the chaotic tidal forces introduced by the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), another nearby satellite galaxy.

Confirming the existence and location of the LMC's supermassive black hole will require further observations using powerful telescopes such as the Hubble Space Telescope or the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Directly imaging the black hole would provide definitive proof of its presence and enable more detailed studies of its properties and influence on the LMC's evolution.

Future Directions and Implications

While the study's conclusions are based on a limited sample of three hypervelocity stars, the results demonstrate the power of using these extreme stellar objects as probes of galactic dynamics. Additional observations to refine the proper motions of the LMC hypervelocity stars could further constrain the galaxy's path and provide valuable insights into the nature of dark matter and its role in shaping the evolution of galaxies.

This research highlights the importance of ongoing and future astronomical surveys, such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), which will discover countless more hypervelocity stars and enable even more precise studies of galactic motion and interaction.

As astronomers continue to unravel the mysteries of the Large Magellanic Cloud and its central supermassive black hole, we move closer to a comprehensive understanding of the intricate gravitational dance that has shaped our galactic neighborhood over billions of years. The groundbreaking work of Lucchini, Han, and their colleagues at the Harvard Center for Astrophysics represents a significant step forward in this cosmic quest.