In the fleeting moments following the Big Bang, our universe existed in a state so fundamentally different from today's cosmos that it would be utterly unrecognizable to us. This is the third installment in our exploration of the mythic dimensions of cosmic origins, where we delve into one of the most profound transformations in universal history: the symmetry breaking that gave birth to the fundamental forces governing our reality. When physicists speak of the "early universe," they're not referring to epochs billions of years in the past—they're discussing the first fractions of a second after creation, when the cosmos was merely 13.77 billion years old by a handful of heartbeats.

What makes this period so extraordinary is that the very fabric of physical law itself was undergoing radical transformation. The forces we take for granted—gravity pulling us to Earth, electromagnetism powering our devices, and the nuclear forces binding atoms—simply did not exist in their current forms. Instead, they were unified in ways that challenge our deepest intuitions about how nature operates.

The Architecture of Force Unification

Modern physics recognizes four fundamental forces that govern all interactions in our universe: gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force. Yet this seemingly immutable quartet represents only the low-energy state of our cooled cosmos. Research conducted at facilities like CERN's Large Hadron Collider has demonstrated that at sufficiently high energies—energies that existed naturally in the primordial universe—these forces begin to merge in a process called force unification.

The first unification occurs at energies around 100 GeV (giga-electron volts), where electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force combine to form the electroweak force. This isn't merely a mathematical convenience or a theoretical construct—it represents a genuine transformation of physical reality. At these energy scales, the photon, which carries electromagnetic force, ceases to exist as a distinct particle. Similarly, the W and Z bosons that mediate weak interactions vanish. In their place emerge new force-carrying particles that belong to this unified electroweak interaction.

Scientists at Fermilab and other particle physics laboratories have extensively studied this electroweak unification, confirming predictions made by theoretical physicists Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg—work that earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979. As the universe expanded and cooled below this critical energy threshold, spontaneous symmetry breaking occurred, splitting the electroweak force into the two distinct forces we observe today.

Grand Unification and the Theory Hierarchy

Pushing to even higher energies—approximately 10^16 GeV—physicists theorize that the strong nuclear force joins this cosmic merger. This hypothetical state is described by a framework called Grand Unified Theories (GUTs), which attempt to unify three of the four fundamental forces under a single mathematical description. While we lack direct experimental evidence for GUT-scale unification (the required energies are far beyond what any conceivable particle accelerator could achieve), several lines of indirect evidence support these theories.

"The elegance of grand unification lies not just in mathematical beauty, but in its ability to explain seemingly arbitrary features of our universe—such as the precise quantization of electric charge—as natural consequences of a deeper symmetry," explains theoretical physicist Frank Wilczek, Nobel laureate and professor at MIT.

At the apex of this hierarchy sits the ultimate unification: the merger of all four forces, including gravity, into a single, coherent framework. This would occur at the Planck energy scale—approximately 10^19 GeV—where quantum effects and gravitational effects become equally important. Theories attempting to describe this ultimate unified state are ambitiously called "theories of everything", though as the article honestly acknowledges, our current candidates like string theory remain incomplete and unproven.

The Strangeness of Primordial Unity

To truly grasp the alien nature of the earliest universe, we must abandon our intuitions about particles and forces. In that primordial state—lasting perhaps 10^-36 seconds after the Big Bang—none of the particles we know existed. There were no electrons orbiting atomic nuclei, no quarks binding together to form protons and neutrons, no neutrinos streaming through space, and no photons carrying light. Even the mysterious dark matter that comprises 85% of the universe's matter content had not yet materialized.

What existed instead was something far more fundamental: a unified field in a state of perfect symmetry and equilibrium. This primordial essence suffused all of reality, undifferentiated and homogeneous. Imagine a perfectly still pond, its surface an unbroken mirror—this captures something of the pristine symmetry of the pre-symmetry-breaking universe, though the analogy barely scratches the surface of its strangeness.

The Violent Birth of Complexity

This elegant unity could not persist. As the universe expanded, it cooled, and as it cooled, it underwent a series of phase transitions—analogous to water freezing into ice, but far more consequential. These weren't gentle transformations but rather the most violent events in cosmic history, compressed into timeframes almost incomprehensibly brief.

The breaking of symmetry occurred in stages, each corresponding to the separation of one of the fundamental forces:

- Gravity Separation (10^-43 seconds): At the Planck time, gravity decoupled from the other forces, becoming the distinct interaction we know today. This epoch remains shrouded in mystery, as we lack a complete theory of quantum gravity.

- GUT Symmetry Breaking (10^-36 seconds): The strong nuclear force separated from the electroweak force, potentially triggering cosmic inflation—a period of exponential expansion that solved several cosmological puzzles.

- Electroweak Symmetry Breaking (10^-12 seconds): The electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces split apart, establishing the force structure we observe today and giving mass to fundamental particles through the Higgs mechanism.

- Quark Confinement (10^-6 seconds): Quarks became permanently bound inside protons and neutrons, unable to exist freely in the cooled universe.

The Asymmetry That Made Us Possible

Among the most profound consequences of symmetry breaking was the emergence of matter-antimatter asymmetry. In the earliest moments, matter and antimatter should have been created in equal quantities. When matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate in a burst of pure energy. If perfect symmetry had been maintained, the universe would contain nothing but photons—no atoms, no stars, no galaxies, no life.

Yet somehow, for reasons still not fully understood, a tiny imbalance emerged: for every billion antimatter particles, there were a billion and one matter particles. This one-part-in-a-billion excess is the origin of everything we see. Research at facilities like the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider attempts to recreate these conditions and understand this crucial asymmetry.

Inflation and the Reheating of the Universe

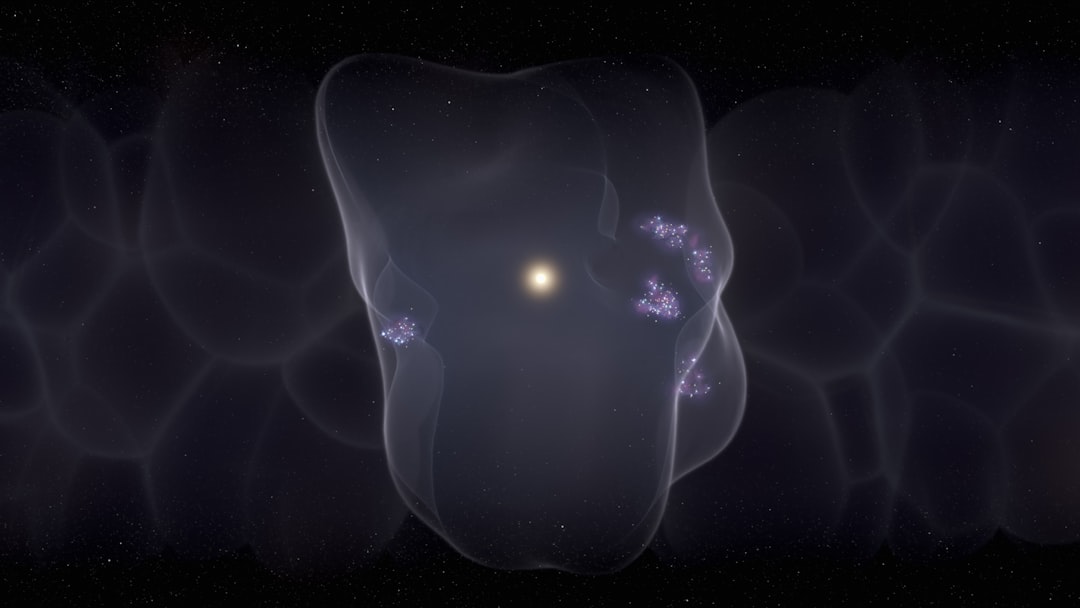

One of the most dramatic consequences of symmetry breaking may have been cosmic inflation—a period when the universe expanded by a factor of at least 10^26 in a fraction of a second. According to inflationary theory, pioneered by Alan Guth and refined by Andrei Linde and others, the energy stored in certain quantum fields during the GUT phase transition drove this exponential expansion.

The inflationary epoch solved several cosmological mysteries: why the universe appears so uniform on large scales (the horizon problem), why space appears geometrically flat (the flatness problem), and why we don't observe magnetic monopoles and other exotic relics predicted by GUTs. According to research published in leading journals and supported by observations from ESA's Planck satellite, inflation stretched quantum fluctuations to cosmic scales, creating the seeds that would eventually grow into galaxies and galaxy clusters.

When inflation ended—as suddenly as it began—the universe found itself in a peculiar state: vastly expanded, but cold and nearly empty. The inflaton field that had driven expansion was now in an unstable, high-energy state. It rapidly decayed in a process called reheating, converting its stored energy into a hot, dense soup of particles and radiation. This was the matter and energy that would eventually form stars, planets, and life itself.

The First Minutes: Nucleosynthesis

In the minutes following reheating, the universe was still hot enough for nuclear reactions to occur freely. During this epoch of Big Bang nucleosynthesis, the first atomic nuclei formed. Protons and neutrons, which had condensed from the quark-gluon plasma just moments earlier, began fusing together to create deuterium (heavy hydrogen), helium, and trace amounts of lithium and beryllium.

The precise abundances of these primordial elements—roughly 75% hydrogen and 25% helium by mass—provide one of the most compelling pieces of evidence for the Big Bang theory. These predictions, made in the 1940s by Ralph Alpher and George Gamow, have been confirmed by astronomical observations with remarkable precision. The agreement between theory and observation stands as a testament to our understanding of these primordial processes.

Legacy of the Primordial Fire

The symmetry-breaking epochs, though brief beyond imagination, established the physical laws and particle content that would govern the subsequent 13.77 billion years of cosmic evolution. Every atom in your body, every photon of sunlight, every gravitational tug from distant galaxies—all trace their origins to these transformative moments.

Understanding these early epochs remains one of the great challenges of modern physics. Future experiments, from next-generation particle colliders to increasingly sensitive observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation, promise to illuminate these primordial mysteries. Each discovery brings us closer to understanding not just what happened in those first moments, but why the universe took the particular path it did—why these forces, these particles, these laws, and not others.

The mythic dimension of the Big Bang lies precisely here: in this narrative of unity breaking into diversity, of symmetry shattering into complexity, of a formless void giving birth to a universe rich with structure and possibility. It's a creation story written in the language of quantum fields and symmetry groups, but no less profound for its mathematical expression.

As we continue this series, we'll explore further aspects of the cosmic creation narrative, examining how the seeds planted in these earliest moments grew into the magnificent cosmos we inhabit today. The journey from those first fractions of a second to the present day spans not just time, but scales of complexity that continue to inspire wonder and drive scientific inquiry.