The story of how humanity came to understand the universe's dynamic nature represents one of the most profound intellectual journeys in modern science. In this second installment exploring the mythological dimensions of cosmological theory, we delve into the revolutionary concept that would eventually become known as the Big Bang theory—a term that wouldn't be coined until decades after its fundamental principles were established. At the heart of this narrative stands a Belgian priest-scientist whose vision of a "primaeval atom" would forever change our understanding of cosmic origins, despite facing skepticism from the very architect of relativity himself.

The early 20th century witnessed a remarkable convergence of mathematical elegance and physical insight. Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, completed after years of intense intellectual labor, provided humanity with an unprecedented framework for understanding gravity not as a mysterious force, but as the curvature of spacetime itself. This revolutionary theory, published in its complete form in 1915, would become the foundation upon which all modern cosmology rests, as documented extensively in the NASA archives on general relativity.

Einstein's Cosmic Equations and Their Unexpected Predictions

With the mathematical machinery of general relativity at his disposal, Einstein turned his attention to the grandest scale imaginable: the entire cosmos. His reasoning was elegantly simple yet profoundly insightful. At sufficiently large scales—spanning millions and billions of light-years—gravity emerges as the dominant force shaping the universe's structure and evolution. The strong and weak nuclear forces, though fundamental to atomic processes, operate only across distances comparable to atomic nuclei, becoming negligible beyond these microscopic scales.

The electromagnetic force, while theoretically infinite in range like gravity, presents a different situation. The universe maintains an overall electrical neutrality, with positive and negative charges distributed in rough equilibrium. This cosmic balance effectively cancels out electromagnetic effects on the largest scales, leaving gravity as the sole architect of universal structure and dynamics.

However, gravity's influence is truly universal. Every particle of matter, every quantum of energy, both generates gravitational effects and responds to the gravitational field created by all other matter and energy. Since the universe encompasses, by definition, all existing matter and energy, Einstein faced a straightforward yet monumental task: apply the equations of general relativity to this cosmic totality and determine how it should evolve over time.

The results shocked him. Rather than describing a static, eternal cosmos—the prevailing assumption among astronomers and philosophers alike—Einstein's equations stubbornly insisted that a universe filled with matter and energy must be dynamically evolving, either expanding or contracting. Unable to accept this revolutionary implication, Einstein made what he would later call his "greatest blunder": he artificially modified his elegant equations by introducing the cosmological constant, a mathematical term designed specifically to stabilize the universe and preserve the static cosmos he believed must exist.

The Priest-Scientist Who Believed the Mathematics

Georges Lemaître, a Belgian physicist and Catholic priest, approached Einstein's equations with fewer preconceptions and greater faith in their mathematical predictions. Lemaître possessed a unique combination of credentials: he held a doctorate in physics from MIT and had studied at Cambridge under Arthur Eddington, one of the early champions of general relativity. His dual identity as both scientist and clergyman would later fuel unfair criticisms of his work, but it also perhaps gave him the philosophical flexibility to accept conclusions that others found uncomfortable.

Working independently in the late 1920s, Lemaître allowed Einstein's field equations to speak for themselves. He derived solutions indicating that the universe should be expanding, with galaxies receding from one another as space itself grew larger. More provocatively, he traced this expansion backward in time, concluding that the universe must have been smaller, denser, and hotter in the past. The European Space Agency's research on cosmic evolution has since confirmed these fundamental insights with extraordinary precision.

When Lemaître first presented his ideas to Einstein at a conference in 1927, the response was devastating. Einstein acknowledged the mathematical correctness of Lemaître's calculations but dismissed the physical interpretation with harsh words:

"Your calculations are correct, but your physics is abominable."

Coming from the most celebrated physicist of the age, this rebuke must have been deeply discouraging. Yet Lemaître persisted, convinced that the mathematics revealed genuine physical truth about the cosmos.

Hubble's Observations Transform Theory into Reality

History vindicated Lemaître with remarkable speed. In 1929, just two years after Einstein's dismissal, astronomer Edwin Hubble announced observations that would revolutionize cosmology. Using the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory—then the world's most powerful astronomical instrument—Hubble had measured the velocities of distant galaxies by analyzing the redshift of their spectral lines.

The pattern was unmistakable and astonishing: with few exceptions, every galaxy appeared to be moving away from us, and more distant galaxies were receding faster than nearby ones. This relationship, now known as Hubble's Law, provided the first direct observational evidence that the universe is expanding. The implications were profound and unavoidable—if galaxies are moving apart now, they must have been closer together in the past. The Hubble Space Telescope Science Institute maintains extensive resources documenting this foundational discovery.

The astronomical community erupted in activity. Theorists scrambled to develop comprehensive models explaining cosmic expansion. In this intellectual ferment, Lemaître quietly reminded his colleagues that he had already developed such a framework. His 1931 paper, published in Nature, presented a complete cosmological scenario that extended far beyond merely describing expansion—it attempted to explain the universe's ultimate origin.

The Primaeval Atom: A Cosmic Creation Story

Lemaître's vision was both audacious and detailed. He proposed that the universe began as what he called the "primaeval atom" or "hypothesis of the primeval atom"—a state of extreme density and energy concentration from which all of space, time, matter, and energy emerged. In his 1931 paper, Lemaître described this cosmic genesis with remarkable specificity:

"This atom is conceived as having existed for an instant only, in fact, it was unstable and, as soon as it came into being, it was broken into pieces which were again broken, in their turn; among these pieces electrons, protons, alpha particles, etc., rushed out. An increase in volume resulted, the disintegration of the atom was thus accompanied by a rapid increase in the radius of space which the fragments of the primeval atom filled, always uniformly."

This description reveals both Lemaître's visionary insight and the limitations of contemporary physics. He correctly envisioned an initial state of extreme density that rapidly expanded, filling an ever-growing volume of space. However, his mechanism—the radioactive decay of a cosmic super-atom—reflected the cutting-edge nuclear physics of his era rather than the quantum processes we now understand governed the early universe.

Lemaître imagined the primaeval atom fragmenting like a radioactive nucleus, with fundamental particles cascading outward. This debris would eventually coalesce under gravity to form the stars, galaxies, and cosmic structures we observe today. While the specific mechanism was incorrect, the broad narrative arc—initial singularity, rapid expansion, particle formation, and gravitational assembly of cosmic structures—remarkably anticipates our modern understanding, as detailed in research from the CERN particle physics laboratory.

Religious Controversy and Scientific Integrity

Lemaître's proposal immediately attracted criticism, much of it tinged with suspicion about his religious vocation. Skeptics accused him of attempting to smuggle the biblical Genesis narrative into scientific cosmology, of allowing theological preconceptions to contaminate objective inquiry. The concern was understandable—a Catholic priest proposing that the universe had a definite beginning, emerging from a singular creation event, seemed almost too convenient.

Lemaître consistently and vigorously rejected these accusations. He maintained a strict separation between his scientific work and his religious faith, arguing that cosmology and theology addressed fundamentally different questions through fundamentally different methods. In his view, he was simply following where the mathematics and observations led, regardless of any superficial resemblance to religious narratives. The fact that the universe appeared to have a beginning was a scientific conclusion derived from physical evidence, not a theological assertion imposed on the data.

This controversy highlights an enduring tension in cosmology: the field necessarily addresses questions—Where did the universe come from? How did it begin? What is its ultimate fate?—that have occupied human mythology, philosophy, and religion for millennia. Modern cosmologists must navigate this terrain carefully, distinguishing empirical scientific conclusions from metaphysical speculation.

Legacy and Modern Understanding

Today, we recognize Lemaître's primaeval atom as the conceptual ancestor of the Big Bang theory, though that term wouldn't be coined until 1949, when British astronomer Fred Hoyle used it dismissively during a BBC radio broadcast. Ironically, Hoyle was a proponent of the rival "Steady State" theory and intended "Big Bang" as a pejorative—yet the name stuck and eventually became the standard designation for the expanding universe model.

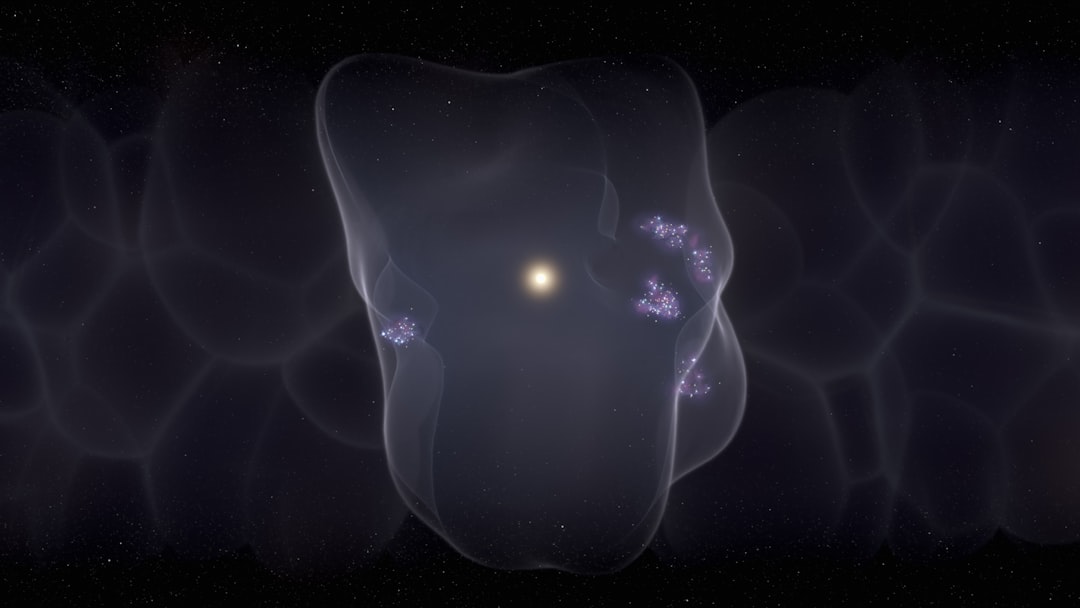

Modern cosmology has refined and corrected many details of Lemaître's original vision. We now understand that the early universe was governed by quantum field theory and particle physics rather than radioactive decay. The concept of cosmic inflation—a brief period of exponential expansion in the universe's first fraction of a second—has been added to explain several otherwise puzzling features of the cosmos. Precise measurements from satellites like the Planck space observatory have determined the universe's age (13.8 billion years), composition, and geometry with remarkable accuracy.

Yet Lemaître's fundamental insights remain valid:

- The universe had a beginning: Approximately 13.8 billion years ago, the cosmos existed in a state of extreme density and temperature, effectively a singularity where classical physics breaks down

- Space itself expands: Galaxies aren't moving through space; rather, space itself grows, carrying galaxies along with it

- The universe evolves: The cosmos has a history, progressing from simple, uniform conditions to the rich complexity we observe today

- Gravity shapes cosmic structure: The attractive force of gravity, acting over billions of years, assembled the hierarchical structure of galaxies, clusters, and superclusters

- Mathematics predicts reality: The equations of general relativity, properly interpreted, reveal genuine truths about the physical universe

The Intersection of Science and Narrative

The story of Lemaître's primaeval atom illuminates how scientific theories function as narratives—not myths in the sense of unfounded stories, but coherent accounts that organize observations, explain phenomena, and make predictions. Every successful scientific theory tells a story about how some aspect of nature works, and cosmology necessarily tells the grandest story of all: the history of everything.

This narrative dimension doesn't diminish cosmology's scientific rigor. Modern Big Bang theory rests on multiple independent lines of evidence: the cosmic expansion discovered by Hubble, the cosmic microwave background radiation (the afterglow of the Big Bang itself), the abundances of light elements produced in primordial nucleosynthesis, and the large-scale structure of galaxy distribution. Each of these observations confirms predictions made by the theory, providing the empirical foundation that distinguishes scientific cosmology from pure speculation or mythology.

Lemaître himself would be astonished and delighted by how thoroughly subsequent observations have validated his core insights. From the cosmic microwave background discovered in 1964 to the accelerating expansion revealed by supernova observations in the 1990s (which ironically rehabilitated Einstein's cosmological constant), the expanding universe model has survived every observational test while continually revealing new mysteries—dark matter, dark energy, the nature of cosmic inflation—that drive ongoing research.

The primaeval atom may have been an imperfect conception, rooted in the incomplete physics of the 1930s, but it represented a crucial step in humanity's quest to understand cosmic origins. Lemaître's willingness to follow the mathematics wherever it led, his courage in proposing a universe with a definite beginning despite the philosophical and theological complications, and his insistence on separating scientific conclusions from religious doctrine all exemplify the best traditions of scientific inquiry. His story reminds us that transformative scientific insights often come from unexpected sources and that the most profound truths about nature may initially seem as strange and mythical as any ancient creation story—until observation and experiment confirm their reality.