In the final installment of our exploration into the mathematical universe hypothesis, we confront the most profound questions about the nature of reality itself: Is mathematics the fundamental fabric of existence, or merely a sophisticated tool we've invented to describe it? This philosophical battleground, where physics meets metaphysics, challenges our deepest assumptions about what it means to understand the cosmos.

The mathematical universe hypothesis, championed by cosmologist Max Tegmark at MIT, proposes that our physical reality isn't just described by mathematics—it is mathematics. Yet this elegant idea, while intellectually seductive, raises as many questions as it attempts to answer. As we peel back the layers of this theory, we find ourselves grappling with ancient philosophical debates that have occupied humanity's greatest thinkers for millennia, from the mystical Pythagoreans to modern theoretical physicists at institutions like CERN and the Institute for Advanced Study.

The journey to understand whether mathematics is discovered or invented isn't merely academic navel-gazing—it strikes at the heart of how we comprehend our place in the universe and the validity of scientific inquiry itself.

The Paradox of Simplicity: When Occam's Razor Cuts Both Ways

At first glance, Occam's Razor—the principle that the simplest explanation is usually correct—seems to support the mathematical universe hypothesis. By stripping away all the "baggage" of physical reality, we arrive at pure mathematical structure. But here's where the argument becomes deliciously paradoxical: to actually explain the universe we observe, we must pile on additional concepts like the multiverse theory, the anthropic principle, and restrictions to specific mathematical structures that avoid paradoxes.

This presents what philosophers of science call a "complexity shift"—we've simply moved the complications from one domain to another. The 14th-century Franciscan friar William of Ockham never intended his razor to be an absolute arbiter of truth. Rather, it serves as a methodological guideline for hypothesis formation. History has repeatedly shown us that reality often chooses complexity over simplicity.

Consider the evolution of physics itself: the elegant simplicity of 19th-century classical mechanics—with its three fundamental forces and deterministic universe—gave way to the bewildering complexity of quantum mechanics, general relativity, and the Standard Model of particle physics. The discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, predicted by theoretical frameworks of staggering mathematical sophistication, demonstrated that nature doesn't always favor the simplest path. If correctness correlated with simplicity, we'd still be teaching Newtonian mechanics as the complete picture of reality.

The Problem of Unrealized Possibilities

One of the most compelling objections to the mathematical universe hypothesis involves what we might call the "ghost particle problem." Theoretical physicists can construct mathematically consistent models of particles, forces, and physical constants that violate no known laws of physics. These hypothetical entities should exist if mathematics alone determines reality—yet they don't appear in our observable universe.

For instance, we could mathematically describe particles with properties intermediate between known quarks and leptons, or additional fundamental forces beyond the four we observe. The equations work perfectly. The mathematics is internally consistent. So why don't these entities exist? If the universe is purely mathematical, what mechanism filters out these possibilities? Who or what acts as the cosmic editor, deciding which mathematical structures get instantiated and which remain abstract?

This selection problem becomes even more acute when we consider the fine-tuning of physical constants. Research from NASA's cosmology programs has shown that even slight variations in fundamental constants would render our universe inhospitable to complex structures, let alone life. The mathematical universe hypothesis must explain why our particular mathematical structure, with its specific parameters, manifests while countless other equally valid mathematical possibilities do not.

The Gödel Conundrum: Transcending Our Mathematical Prison

Perhaps the most intellectually fascinating challenge to the mathematical universe hypothesis comes from Gödel's incompleteness theorems, proven by Kurt Gödel in 1931. These theorems demonstrate that any sufficiently complex mathematical system contains true statements that cannot be proven within that system itself. Yet humans can recognize these unprovable truths by stepping outside the formal system and viewing it from a meta-mathematical perspective.

Here's the puzzle: if we are made entirely of mathematics—particularly the "simpler" mathematics that Tegmark argues avoids paradoxes—how can we transcend our own mathematical foundation? How can the human mind, presumably operating according to mathematical principles, generate mathematics more complex than the mathematical structure that supposedly constitutes our universe?

"The ability of conscious beings to recognize mathematical truths that transcend formal proof systems suggests either that consciousness involves non-computational elements, or that the mathematical structure of our universe is far more complex than we imagine—possibly complex enough to include the very mechanisms by which we understand mathematics itself."

This creates what philosophers call a "strange loop"—a hierarchical paradox where we find ourselves both inside and outside the system simultaneously. Cognitive scientists and philosophers of mind at institutions like the Santa Fe Institute continue to grapple with these questions at the intersection of mathematics, physics, and consciousness.

The Evidence Question: Can We Test Mathematical Reality?

Tegmark argues that discovering a Theory of Everything—a complete mathematical description unifying all physical forces and phenomena—would support the mathematical universe hypothesis. But this reasoning contains a logical gap. A comprehensive mathematical description of physics might equally well support several alternative interpretations:

- Mathematical Platonism: Mathematics exists in an abstract realm, and physical reality imperfectly instantiates these forms

- Structural Realism: Only the mathematical relationships between things are real; the "things" themselves are secondary

- Instrumentalism: Mathematics is simply an extraordinarily effective tool for prediction, without ontological implications

- Naturalistic Dualism: Both mathematical and physical aspects of reality are fundamental and irreducible to each other

The challenge is that the mathematical universe hypothesis, as currently formulated, doesn't make unique, testable predictions that would distinguish it from these alternatives. This raises questions about whether it qualifies as a scientific theory in the Popperian sense—can it be falsified? Without empirical consequences that differ from competing frameworks, we venture into the realm of metaphysics rather than physics.

Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Physics: The Pythagorean Legacy

The debate over mathematical reality isn't new. Twenty-five centuries ago, the Pythagorean school in ancient Greece proclaimed that "all is number." For these philosophical mathematicians, geometric relationships and numerical ratios weren't merely descriptions of reality—they were reality itself, divine truths accessible through contemplation and study. The Pythagorean theorem wasn't just a useful tool for surveying land; it was a mystical revelation about the fundamental structure of existence.

This ancient perspective resurfaces in modern form through the mathematical universe hypothesis. But we must ask: has our mathematics become more sophisticated, or have we simply dressed ancient mysticism in the language of contemporary physics? The question of whether mathematics is discovered or invented remains as contentious today as it was in Pythagoras's time.

If mathematics is discovered, it possesses an independent existence—the statement "2+2=4" holds true whether or not any physical objects exist to count, whether or not any minds exist to conceive of it. The circumference of a circle equals 2π times its radius in some abstract realm beyond space and time. Under this view, mathematicians are explorers charting a pre-existing landscape of mathematical truth.

But perhaps mathematics is invented—a sophisticated cognitive tool evolved and refined to solve practical problems. Early humans needed to predict seasonal floods, calculate harvest yields, and establish fair trade. Mathematics emerged from these concrete needs. The fact that mathematics "works so well" might reflect selection bias: we've developed mathematical frameworks specifically because they're useful for describing patterns we encounter. As the saying goes, if your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. If you view the world through mathematical frameworks, the universe naturally appears mathematical.

Beyond the Equations: The Limits of Mathematical Description

Even if we achieved a complete Theory of Everything—a set of equations describing all physical phenomena—profound aspects of reality would remain outside its scope. Consider the subjective experience of perceiving the color orange, the emotional weight of grief, the aesthetic appreciation of a sunset, or the moral dimension of justice. These qualia—the felt qualities of conscious experience—resist mathematical formalization.

Neuroscientists can map the neural correlates of these experiences, tracking electrical patterns and chemical cascades in the brain. But the mathematical description of neurons firing doesn't capture what it feels like to experience those states. This is philosopher David Chalmers's famous "hard problem of consciousness"—explaining why physical processes give rise to subjective experience at all.

If mathematics constitutes ultimate reality, where do these irreducibly subjective aspects fit? Are they illusions? Emergent properties that somehow transcend their mathematical substrate? Or do they point to dimensions of reality that mathematics cannot capture?

The Metaphor of Hamlet: Existence Across Domains

Consider a thought experiment that illuminates the puzzle of mathematical existence: Does Shakespeare's Hamlet exist? In one sense, obviously yes—you can download it, read it, watch performances. But imagine every copy destroyed, every memory erased. Would Hamlet still exist as a particular sequence of words within the vast space of all possible word combinations?

The answer exists in a strange liminal space—yes and no simultaneously. The abstract possibility of Hamlet exists in the combinatorial space of language, just as all possible mathematical structures exist in some Platonic realm. But it required Shakespeare's creative act to actualize this particular combination, to make it real in a different, more tangible sense.

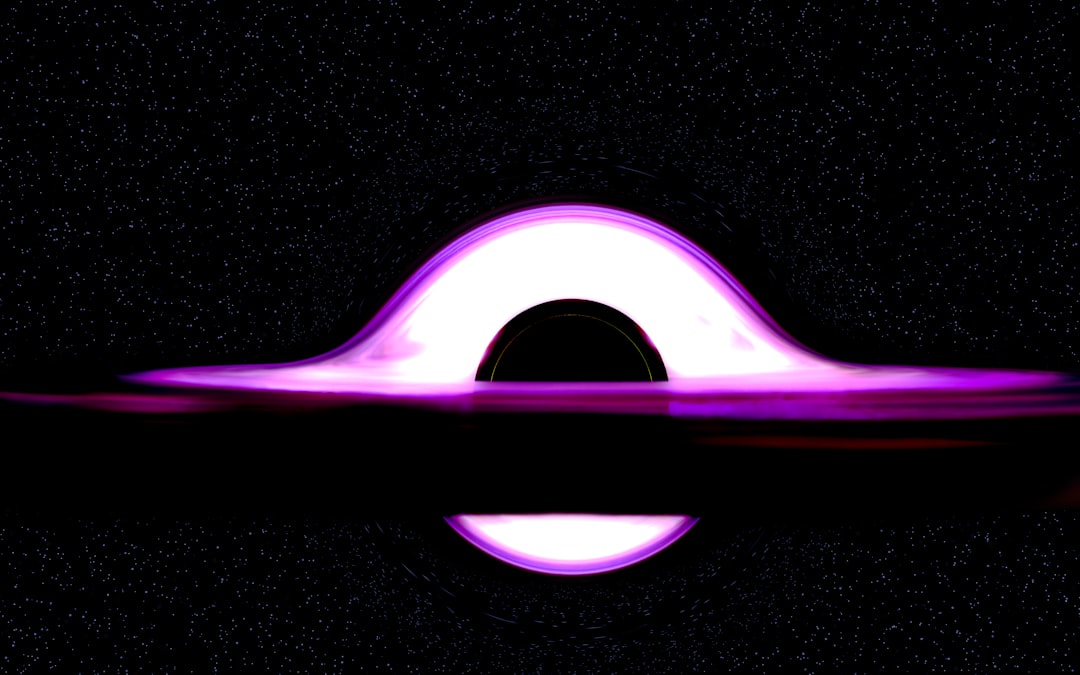

This metaphor captures something essential about the relationship between mathematical possibility and physical reality. Even if all mathematical structures exist abstractly, something must "breathe fire into the equations," as Stephen Hawking memorably phrased it. What transforms mathematical possibility into physical actuality?

"What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe?" - Stephen Hawking

The possible answers span the full range of philosophical positions: perhaps there is no fire—only mathematics exists, and physical reality is an illusion. Perhaps God serves as the actualizing principle. Perhaps consciousness itself plays this role. Or perhaps the question contains a category error, and we're asking about a distinction that doesn't ultimately exist.

The Meaning in the Mystery

The mathematical universe hypothesis forces us to confront fundamental questions about the nature of reality, knowledge, and existence itself. These aren't merely abstract philosophical puzzles—they shape how we approach scientific inquiry and understand our place in the cosmos. Research programs at facilities like ESA's space science division continue pushing the boundaries of what we can observe and measure, potentially bringing us closer to answers.

Whether you find the mathematical universe hypothesis compelling or problematic likely depends on your intuitions about mathematics itself. Is it the deepest layer of reality, or one descriptive framework among many? Are we discovering eternal truths, or inventing useful fictions?

Perhaps the greatest value of this hypothesis lies not in its correctness, but in how it challenges us to examine our assumptions. In wrestling with these questions—in the very act of inquiry itself—we might be fulfilling the universe's deepest purpose. The cosmos has evolved structures complex enough to contemplate their own existence, to ask why there is something rather than nothing, to wonder whether reality is mathematics or mathematics describes reality.

Maybe the fire that breathes life into the equations is the asking itself. Maybe consciousness, inquiry, and wonder are how the universe comes to know itself. In pondering whether we're made of mathematics, we're engaging in the most profound form of cosmic self-reflection—and perhaps that's enough.