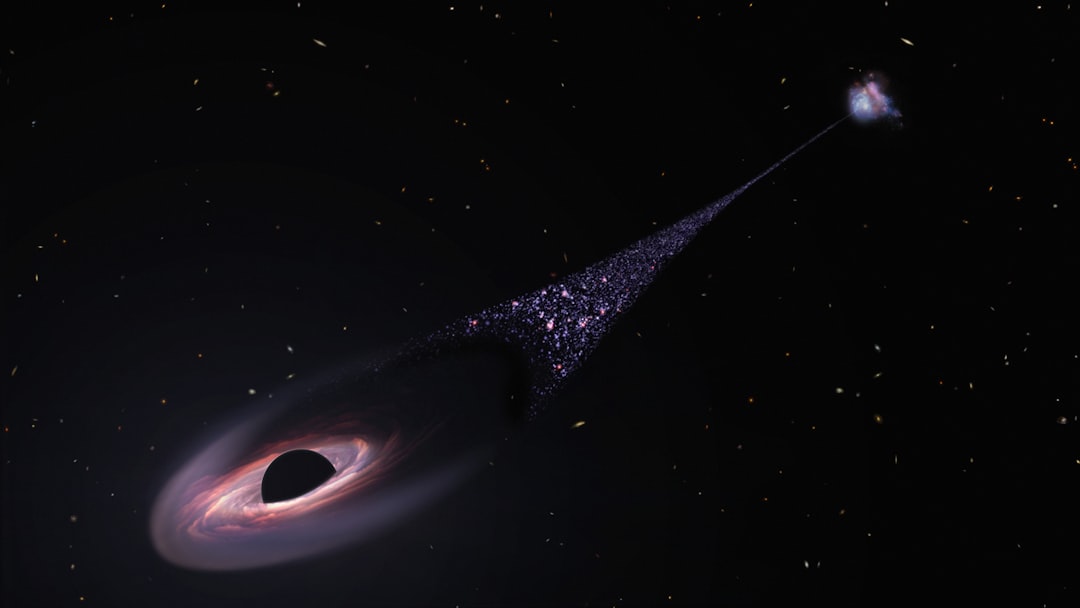

A groundbreaking investigation into cosmic archaeology has revealed compelling evidence that Earth experienced a close encounter with a supernova explosion approximately 10 million years ago. The research, recently submitted to Astronomy & Astrophysics, demonstrates how scientists can use isotopic fingerprints buried in ocean sediments to reconstruct dramatic celestial events that occurred during Earth's geological past. This discovery not only illuminates a pivotal moment in our planet's cosmic history but also provides crucial insights into how stellar explosions shape the conditions for life throughout the universe.

By analyzing rare isotopes deposited across the Pacific Ocean floor and cross-referencing them with ESA's Gaia mission data, researchers have pieced together a cosmic detective story spanning millions of years. The findings suggest that our solar system passed through debris from a relatively nearby stellar explosion, leaving behind chemical signatures that persist to this day. This research represents a convergence of multiple scientific disciplines—from astrophysics and cosmochemistry to geology and astrobiology—offering a window into how cosmic events influence planetary environments and potentially the evolution of life itself.

Decoding Cosmic Rays Through Beryllium-10 Analysis

The key to unlocking this ancient cosmic event lies in an unusual isotope called beryllium-10 (10Be), a radioactive element that doesn't occur naturally on Earth through normal geological processes. Instead, 10Be forms when high-energy cosmic rays collide with oxygen and nitrogen atoms in Earth's upper atmosphere. These cosmic rays—essentially atomic nuclei traveling at nearly the speed of light—can be dramatically enhanced by nearby supernova explosions, which act as nature's most powerful particle accelerators.

What makes 10Be particularly valuable for this research is its half-life of 1.39 million years. This relatively short decay period (in geological terms) means that any significant concentrations found in sediment layers can be dated with reasonable precision and linked to specific cosmic events. According to research from cosmogenic nuclide studies, when 10Be levels spike dramatically above background levels, it serves as a smoking gun for increased cosmic ray bombardment—potentially indicating a nearby supernova explosion.

The research team meticulously examined sediment cores from both the central and northern Pacific Ocean, analyzing layers that accumulated between 9.0 and 11.5 million years ago. The isotopic anomaly they discovered peaked approximately 10 million years ago, suggesting a concentrated period of enhanced cosmic ray activity. This spike couldn't be explained by normal solar activity or variations in Earth's magnetic field, pointing instead to an extraordinary extraterrestrial source.

Stellar Forensics: Tracing the Supernova's Origin

To identify the potential culprit behind this cosmic bombardment, researchers turned to Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3), an astronomical catalog containing precise positions, distances, and motions for more than 1.8 billion stars. By reconstructing the positions of star clusters as they existed 10 million years ago, the team could identify which stellar groups were close enough to Earth to have produced the observed 10Be signature.

The investigation revealed that the supernova likely occurred between 35 parsecs (114 light-years) and 100 parsecs (326 light-years) from Earth. While this might seem like a vast distance—and indeed it is by human standards—in astronomical terms, this represents the solar system's immediate cosmic neighborhood. The NASA Hubble Space Telescope studies have shown that supernovae within this range can significantly impact planetary atmospheres through both immediate radiation and prolonged cosmic ray bombardment.

"In conclusion, we find that a nearby SN [supernova] remains a possible explanation for the 10Be anomaly, especially given the Solar System's proximity to the Orion region during that period. The estimated SN probability is nonzero at 35pc and increases with distance, with ASCC20 and OCSN61 emerging as the most promising candidate clusters."

Two star clusters emerged as prime suspects: ASCC20 and OCSN61. ASCC20 appears to be the primary contributor for supernovae occurring up to 70 parsecs away, while OCSN61 becomes increasingly relevant for more distant explosions. Both clusters are associated with the Orion star-forming region, a vast stellar nursery that was positioned much closer to our solar system 10 million years ago than it is today. The Orion region is known for producing massive stars that live fast and die young, making it a hotspot for supernova activity.

The Danger Zone: Understanding Supernova Threat Distances

Not all supernovae pose equal threats to life on Earth. The impact of these stellar explosions depends critically on their distance, with astronomers having identified several key threshold zones based on extensive modeling and observations from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Supernovae occurring beyond 150 parsecs (489 light-years) are considered essentially harmless to Earth's biosphere. At these distances, the cosmic rays and radiation are sufficiently diluted by space that they produce negligible effects on our planet's atmosphere or surface. However, as the distance decreases, the potential impacts become increasingly severe:

- 100-150 parsecs: Minimal atmospheric disruption, slight increase in cosmic ray flux, no significant biological impact

- 50-100 parsecs: Moderate ozone depletion, enhanced cosmic ray exposure, potential climatic effects from atmospheric chemistry changes

- 25-50 parsecs: Significant ozone layer damage, increased surface radiation, potential mass extinction events for some species

- Under 25 parsecs: Catastrophic ozone destruction, lethal radiation levels, mass extinction highly probable

The 10-million-year-old supernova investigated in this study falls into the moderate impact zone. While not close enough to cause immediate mass extinction, it would have subjected Earth to prolonged radiation bombardment lasting between 10,000 and 100,000 years. This extended exposure could have driven evolutionary changes, influenced climate patterns, and altered atmospheric chemistry in ways that might still be detectable in the geological record.

A History Written in Iron and Beryllium

The supernova event 10 million years ago is not an isolated incident in Earth's cosmic history. Scientists have identified multiple episodes of nearby stellar explosions by analyzing different isotopic signatures preserved in various geological archives. In addition to the 10Be anomaly, researchers have discovered spikes in iron-60 (60Fe), another telltale isotope that forms primarily in supernova explosions and has a half-life of 2.6 million years.

Evidence from 60Fe studies points to supernova events occurring approximately 2.6 million years ago and 6-8 million years ago. These discoveries suggest that Earth has experienced multiple close encounters with stellar explosions during relatively recent geological history. The 2.6-million-year-old event is particularly intriguing because it coincides roughly with the beginning of the Pleistocene epoch and significant climate changes on Earth, though establishing a direct causal link remains challenging.

What's remarkable about these isotopic records is their preservation across millions of years. Both 10Be and 60Fe become incorporated into sediments and can even be found in deep-sea manganese crusts, ice cores, and terrestrial deposits. This multi-archive approach allows scientists to cross-validate their findings and build a more complete picture of Earth's exposure to cosmic events.

Implications for Astrobiology and the Search for Habitable Worlds

Understanding how supernovae interact with planetary environments extends far beyond Earth's history—it's crucial for assessing the habitability of exoplanets and the prevalence of life throughout the galaxy. The NASA Exoplanet Exploration program considers supernova frequency and distribution when evaluating potentially habitable zones in the galaxy.

Regions of the Milky Way with high rates of star formation—and consequently high supernova rates—may be less conducive to the development of complex life. The galactic habitable zone hypothesis suggests that life is most likely to thrive in regions where stellar density is neither too high (leading to frequent supernova disruptions) nor too low (limiting the availability of heavy elements necessary for planet formation and life). Earth's position in the galaxy, in a relatively quiet spiral arm, may be one of the factors that has allowed life to flourish for billions of years.

The research also has implications for understanding atmospheric evolution on other worlds. When searching for biosignatures on exoplanets—such as oxygen, ozone, or methane—astronomers must consider how nearby supernovae might alter these atmospheric markers. A planet might temporarily lose its ozone layer or experience changes in atmospheric chemistry that could be misinterpreted as signs of biological activity or its absence.

Future Directions: Expanding the Cosmic Archive

While this study provides compelling evidence for a supernova 10 million years ago, significant questions remain. The researchers emphasize that future investigations must examine 10Be records from terrestrial archives outside the Pacific Ocean to determine whether the observed anomaly represents a global signal or a regional effect confined to specific ocean basins. If the signal is truly global, it would strengthen the supernova hypothesis; if it's regional, alternative explanations—such as localized geological or oceanographic processes—would need to be considered.

Advanced techniques being developed for the next generation of space telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope, will enable astronomers to study supernova remnants with unprecedented detail. By combining these observations with improved models of cosmic ray propagation and better understanding of how these particles interact with planetary atmospheres, scientists will refine their ability to predict the impacts of future supernova events.

The study represents a beautiful synthesis of multiple scientific disciplines—astrophysics, planetary science, atmospheric chemistry, geology, climate science, biology, and cosmochemistry—all working together to understand how cosmic events shape the conditions for life. As we continue to explore our cosmic neighborhood and search for life beyond Earth, understanding the frequency and impact of supernovae will remain a critical piece of the puzzle.

What new revelations about ancient supernovae await discovery in the coming years? As researchers develop more sensitive detection methods, analyze additional isotopic markers, and extend their investigations to other geological archives around the world, we can expect to uncover an increasingly detailed history of Earth's cosmic encounters. Each discovery not only illuminates our planet's past but also helps us understand the cosmic context in which life emerges and evolves throughout the universe. This is the essence of scientific exploration—connecting the dots between Earth's geological record and the vast cosmic drama playing out across the galaxy, one isotope at a time.