One of the most perplexing mysteries in modern cosmology is deepening: measurements of how rapidly our universe expands continue to yield conflicting results that challenge our fundamental understanding of cosmic evolution. In a groundbreaking study, astrophysicists at the University of Tokyo's Research Centre for the Early Universe have employed an entirely independent measurement technique that provides compelling new evidence this discrepancy—known as the Hubble tension—represents genuine physics rather than experimental error. Their findings, which utilize gravitational lensing as a cosmic measuring tool, align with observations of the nearby universe while contradicting predictions based on the primordial cosmos, suggesting we may be on the verge of discovering new fundamental physics.

The research, led by Project Assistant Professor Kenneth Wong and his international collaborators, represents decades of meticulous observation and analysis across multiple telescope facilities, including data from the revolutionary James Webb Space Telescope. By measuring the expansion rate through time delay cosmography—a method that sidesteps traditional measurement approaches entirely—the team has added crucial independent confirmation to one side of this cosmic controversy, intensifying the urgency for cosmologists to explain why the universe appears to expand at different rates depending on how we measure it.

The Cosmic Speed Limit: Understanding the Hubble Constant

At the heart of this mystery lies the Hubble constant, named after astronomer Edwin Hubble who first discovered the universe's expansion in 1929. This fundamental value describes the rate at which space itself stretches, carrying galaxies away from each other. The constant is typically expressed in kilometers per second per megaparsec—meaning for every 3.26 million light-years of distance from Earth, objects appear to recede at a specific additional velocity.

For nearly a century, astronomers have refined measurements of this cosmic expansion rate using what's known as the "cosmic distance ladder". This technique relies on a carefully calibrated chain of distance measurements, starting with nearby stars whose distances we can measure directly, then extending outward to more distant objects. The most distant rungs of this ladder employ Type Ia supernovae—stellar explosions that serve as remarkably consistent "standard candles" because they always reach approximately the same peak brightness. By comparing how bright these supernovae appear versus how bright they actually are, astronomers can calculate their distance with impressive precision.

Using these methods, observations of the local universe—regions within a few billion light-years of Earth—consistently yield a Hubble constant of approximately 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec. Teams using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and other facilities have repeatedly confirmed this value with increasing precision over the past two decades.

The Early Universe Tells a Different Story

The tension emerges when cosmologists calculate what the expansion rate should be based on observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—the faint afterglow of radiation left over from the Big Bang itself. This ancient light, emitted just 380,000 years after the universe's birth, carries encoded information about the cosmos's fundamental properties and composition at that primordial epoch.

The European Space Agency's Planck satellite and other missions have mapped this cosmic microwave background radiation with extraordinary detail. By analyzing the pattern of tiny temperature fluctuations in this radiation, cosmologists can determine the universe's composition, geometry, and initial conditions. Using our best theoretical model—the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) model—they can then calculate how fast the universe should be expanding today based on how it evolved from those early conditions.

The result is troubling: this method predicts a Hubble constant of approximately 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec—a significant 9% discrepancy from the local universe measurements. While that might seem like a small difference, in the precision world of modern cosmology, it represents a five-sigma tension—meaning there's less than a one-in-a-million chance this discrepancy is due to random statistical fluctuation.

"If systematic errors plague either traditional distance ladders or cosmic microwave background analyses, this new method should remain unaffected. The fact that it aligns with present-day observations rather than early universe predictions strengthens the case that the Hubble tension represents real physics," explains Professor Wong.

Gravitational Lensing: A New Cosmic Speedometer

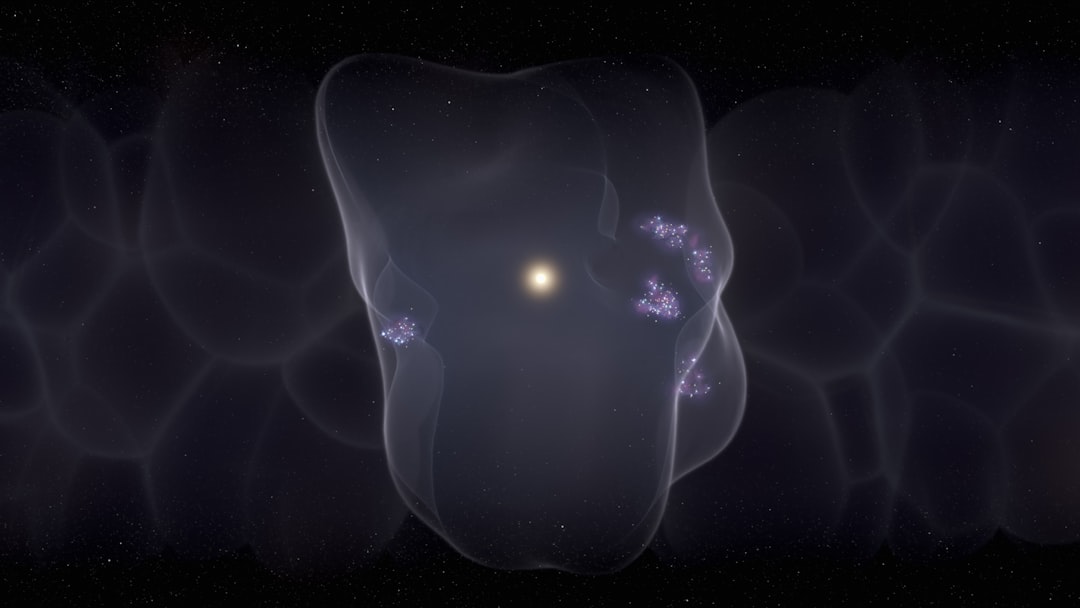

The Tokyo-led research team's approach exploits one of nature's most spectacular optical phenomena: gravitational lensing. As predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity, massive objects warp the fabric of spacetime around them, bending the path of light rays that pass nearby. When a massive galaxy lies almost directly between Earth and a more distant bright object like a quasar, the galaxy acts as a cosmic lens, bending and magnifying the quasar's light.

In particularly fortuitous alignments, a single distant quasar appears as multiple distorted images arranged around the lensing galaxy—sometimes in spectacular formations called Einstein rings or Einstein crosses. Each of these images represents light that has traveled a different path around the lensing galaxy to reach our telescopes. Because these paths have different lengths and pass through regions of spacetime warped to different degrees, light traveling along each path takes a different amount of time to complete its journey.

Quasars are not static objects—they flicker and vary in brightness over timescales of days to months as material swirls into their central supermassive black holes. When astronomers monitor a gravitationally lensed quasar system over months or years, they observe these brightness variations occurring in each image, but offset in time. One image might brighten, then days or weeks later, another image shows the identical brightening pattern. This time delay between images directly reveals the difference in light travel time between the paths.

The beauty of time delay cosmography lies in its independence from other measurement methods. By combining the measured time delays with detailed models of how mass is distributed within the lensing galaxy—determined through careful analysis of the distorted images—astronomers can calculate the absolute distances involved. This, in turn, reveals the expansion rate of the universe without relying on distance ladders or cosmic microwave background physics.

Advanced Observational Campaign

Wong's team analyzed eight carefully selected gravitational lens systems, each featuring a massive foreground galaxy distorting light from a distant background quasar. The observations drew upon data from multiple world-class facilities, including cutting-edge infrared observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, which can peer through cosmic dust and observe the detailed structure of lensing galaxies with unprecedented clarity.

The analysis required sophisticated modeling techniques to map the three-dimensional distribution of both visible and dark matter within each lensing galaxy. The largest source of uncertainty in time delay cosmography comes from these mass models—astronomers must make assumptions about how matter arranges itself within galaxies, typically based on observations of similar galaxies and theoretical expectations from galaxy formation simulations.

Despite these challenges, the team's measurement yielded a Hubble constant consistent with the 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec value from local universe observations—not the 67 predicted by early universe measurements. This independent confirmation using a completely different physical method significantly strengthens the case that the Hubble tension represents a genuine mystery rather than subtle errors in either the distance ladder or cosmic microwave background approaches.

Implications: New Physics on the Horizon?

The persistence of the Hubble tension across multiple independent measurement methods suggests we may be witnessing the first cracks in our current cosmological model. Several theoretical possibilities could explain the discrepancy:

- Early Dark Energy: An additional component of dark energy that was active in the early universe but has since faded could have accelerated the universe's early expansion, leading to different predictions for today's expansion rate.

- Modified Gravity: Perhaps Einstein's general relativity requires subtle modifications on cosmic scales, changing how the universe's expansion evolves over time.

- Dark Radiation: Unknown particles that behaved like radiation in the early universe could have altered the cosmic expansion history in ways not accounted for in current models.

- Evolving Dark Energy: The mysterious dark energy driving the universe's accelerating expansion might change its properties over cosmic time, rather than remaining constant as current models assume.

Each of these scenarios would represent revolutionary new physics, fundamentally changing our understanding of the universe's composition and evolution. The cosmology community has intensified efforts to resolve the tension, with numerous research groups pursuing both improved measurements and theoretical explanations.

The Path Forward: Achieving Definitive Precision

While the Tokyo team's measurement represents a significant milestone, the current precision of approximately 4.5 percent uncertainty leaves room for the tension to potentially resolve itself with improved measurements. To definitively confirm that the Hubble tension represents genuine new physics rather than remaining systematic errors, cosmologists need to push the precision to 1-2 percent—a factor of two to four improvement.

Achieving this goal will require analyzing many more gravitational lens systems and developing increasingly sophisticated models of mass distribution within lensing galaxies. Upcoming surveys using facilities like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which will begin operations soon, are expected to discover hundreds of new strongly lensed quasar systems suitable for time delay cosmography. The James Webb Space Telescope's continued observations will provide crucial high-resolution imaging to constrain lens galaxy properties with unprecedented detail.

Additionally, researchers are developing new techniques to break degeneracies in mass modeling, including using stellar kinematics—measurements of how stars move within lensing galaxies—to independently constrain the dark matter distribution. Machine learning approaches are also being applied to automate and improve the analysis of lens systems, potentially allowing rapid analysis of the large samples needed for percent-level precision.

A Transformative Moment in Cosmology

The convergence of evidence from multiple independent methods—distance ladders, time delay cosmography, and potentially other emerging techniques—suggests we are approaching a transformative moment in our understanding of the cosmos. If the Hubble tension proves irreducible with improved measurements, it would join a select group of observational anomalies that have historically heralded paradigm shifts in physics.

The discovery of the cosmic microwave background itself in 1965 confirmed the Big Bang theory. The observation of accelerating cosmic expansion in 1998 revealed dark energy and earned a Nobel Prize. The resolution of the Hubble tension—whether through discovering new physics or identifying subtle systematic errors—will similarly represent a watershed moment in cosmology.

As Professor Wong and his colleagues continue their work, supported by international collaborations spanning continents and decades, the astronomical community watches with anticipation. The universe is expanding, but the full story of how and why remains tantalizingly just beyond our current grasp. Each new measurement brings us closer to understanding whether we need to revise our cosmic models or refine our observational techniques—and either outcome promises to deepen our comprehension of the universe's grand narrative from the Big Bang to the present day and beyond.