Understanding the expansion of the universe remains one of the most profound challenges in modern cosmology. Unlike everyday experiences where objects expand into surrounding space, cosmic expansion operates fundamentally differently—the universe itself is growing, carrying galaxies along with it like raisins in rising bread dough. This concept, first discovered by Edwin Hubble in 1929, continues to perplex and fascinate scientists and the public alike. The key to grasping this phenomenon lies not in finding the perfect analogy, but in understanding how dimensional perspectives shape our perception of cosmic reality.

The challenge of comprehending universal expansion stems from our inherently three-dimensional perspective. We naturally seek a center point, an edge, or a boundary—concepts that simply don't apply to the cosmos as a whole. According to general relativity and modern cosmological models, the universe has no privileged central location, and every point can legitimately claim to be at the "center" of observable expansion. This counterintuitive reality requires us to think in ways that transcend our everyday spatial reasoning.

To navigate this conceptual difficulty, cosmologists have developed powerful thought experiments that help us visualize expansion without requiring impossible perspectives. By examining how dimensional reduction affects our understanding of centers and boundaries, we can begin to grasp how a four-dimensional spacetime can expand uniformly in all directions simultaneously, with no special origin point and no edge to speak of.

The Surface Analogy: Rethinking Centers and Boundaries

Consider Earth's geography from a completely new perspective. When asked to identify Earth's center, the answer seems obvious—it's the molten iron-nickel core approximately 6,371 kilometers beneath our feet. This three-dimensional center point is well-defined and measurable. However, this straightforward answer reveals our dimensional assumptions.

Now consider a more challenging question: Where is the center of Earth's surface? Not the entire spherical planet, but specifically the two-dimensional surface we inhabit. This question has no meaningful answer. Is it the North Pole, with its geographic significance? The South Pole, with its symmetry? Perhaps the Prime Meridian at Greenwich Observatory, where longitude equals zero? Or the equator, where latitude reaches zero?

These coordinate systems are entirely arbitrary conventions established by human agreement. The Prime Meridian passes through Greenwich simply because of historical circumstances and international agreement in 1884. The equator's definition relies on Earth's rotation axis, itself a consequence of planetary formation rather than any fundamental cosmic principle. Any point on Earth's surface has an equally valid claim to being the "center"—which means, effectively, that no point is the center at all.

"The universe has no center in the same way that Earth's surface has no center. Every observer, regardless of their location, sees themselves at the middle of their own observable universe, with galaxies receding in all directions equally."

This centerless geometry perfectly mirrors the structure of our universe. Just as Earth's surface is a two-dimensional manifold embedded in three-dimensional space, our universe is a three-dimensional manifold that may be curved in higher dimensions we cannot directly perceive. The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) data confirms that the universe appears remarkably uniform and isotropic on large scales, supporting this centerless model.

Visualizing Expansion Without External Perspective

Imagine Earth's surface beginning to expand uniformly. Cities drift farther apart, oceans widen, continents separate at accelerating rates. From space, an external observer could easily watch this expansion, measuring how the planet's radius increases over time. But here's the critical constraint: no such external perspective exists for the universe itself.

We cannot step outside the universe to watch it expand because there is no "outside." Any hypothetical external space would, by definition, be part of the universe. This limitation isn't merely practical—it's fundamental to the nature of cosmic expansion. According to general relativity, spacetime itself is expanding, not objects moving through pre-existing space.

Yet inhabitants confined to Earth's expanding surface could still detect and measure the expansion through several observable effects:

- Increased travel times: Journeys between cities would take progressively longer as distances grew, even at constant speeds

- Cosmological redshift: Light from distant cities would be stretched to longer wavelengths, appearing redder due to the expanding medium through which it travels

- Hubble-like relationships: More distant locations would recede faster, following a linear velocity-distance relationship

- Cooling radiation: Any uniform background radiation would decrease in temperature as wavelengths stretched

These same observational signatures allow cosmologists to confirm universal expansion. The Planck satellite has measured the cosmic microwave background radiation with unprecedented precision, revealing the cooled remnant of the early universe's intense heat, now stretched by expansion to microwave wavelengths.

The Cosmic Horizon: Limits of Observable Reality

Just as Earth's curvature creates a horizon beyond which we cannot see, the universe has its own observational boundary—the cosmic horizon. This limitation arises from the combination of the universe's finite age and light's finite speed. Even in a hypothetical static, non-expanding universe, we could only observe regions from which light has had sufficient time to reach us since the beginning.

The observable universe forms a sphere around Earth (or any observer) containing all the light that has reached us across cosmic history. Think of it as illuminating a dark forest with a flashlight—there's a boundary between the lit region we can see and the unknown darkness beyond. This boundary doesn't represent an edge to the universe itself, merely the limit of what we can currently observe.

In a static universe, calculating this boundary would be straightforward: multiply the universe's age by the speed of light. With an age of approximately 13.8 billion years, this would yield an observable radius of 13.8 billion light-years. Cosmologists call this fundamental distance scale the Hubble radius or Hubble distance, honoring Edwin Hubble's pioneering discovery of cosmic expansion.

The Time-Distance Connection

The cosmic horizon represents more than just a spatial boundary—it's fundamentally a temporal limit as well. Because light travels at finite speed, looking deeper into space means looking further back in time. We observe the Sun not as it exists now, but as it appeared eight minutes ago when the light we're currently receiving began its journey. The Andromeda Galaxy appears as it was 2.5 million years ago. The most distant galaxies detected by the James Webb Space Telescope appear as they existed when the universe was merely a few hundred million years old.

This creates a remarkable structure to our observable universe. The regions closest to us appear relatively contemporary, showing galaxies in their current evolutionary states. As we observe progressively more distant regions, we witness increasingly younger cosmic epochs. At the very edge of observability lies the cosmic microwave background—light released when the universe was only 380,000 years old, when it first became transparent to radiation.

This outermost shell represents the earliest moment we can observe through electromagnetic radiation. Beyond it lies the opaque plasma of the even earlier universe, inaccessible to traditional telescopes but potentially detectable through gravitational waves or neutrino observations. The observable universe thus functions as both a spatial volume and a temporal archive, with distance serving as a proxy for cosmic age.

Expansion's Effect on Cosmic Horizons

The actual expansion of the universe dramatically complicates these calculations. Space itself has been stretching throughout cosmic history, meaning that objects we observe today are considerably farther away than simple light-travel-time calculations would suggest. A galaxy whose light has traveled for 13 billion years is not 13 billion light-years away—it's actually more than 30 billion light-years distant due to the expansion that occurred while the light was in transit.

This expansion creates the counterintuitive result that our observable universe has a radius of approximately 46.5 billion light-years, despite being only 13.8 billion years old. The difference arises because space has been expanding continuously, carrying distant galaxies to greater distances even as their ancient light travels toward us.

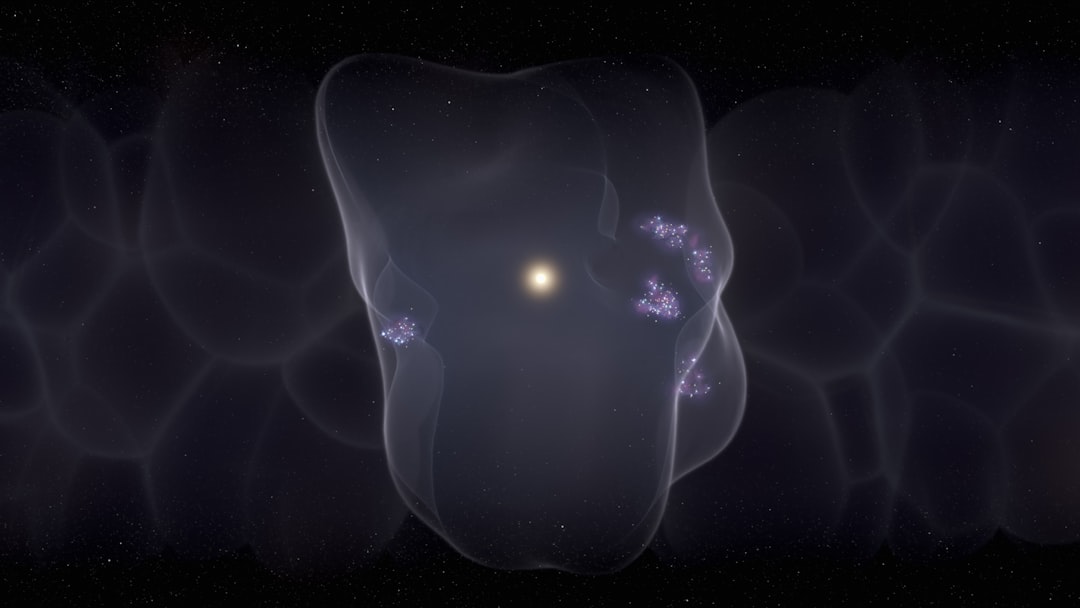

Furthermore, the universe's expansion rate hasn't been constant. Early in cosmic history, expansion was decelerating due to gravitational attraction. However, observations of distant supernovae revealed that expansion began accelerating approximately 5 billion years ago, driven by the mysterious dark energy that comprises roughly 68% of the universe's total energy density. This acceleration means that galaxies beyond a certain distance are receding faster than light can travel toward us, creating a cosmic event horizon—regions of space we will never be able to observe, regardless of how long we wait.

Implications for Cosmic Understanding

Understanding the universe's expansion without a center or edge fundamentally reshapes our cosmic perspective. We recognize that our observable universe—vast as it is—represents merely a tiny fraction of a potentially infinite cosmos. Every galaxy cluster, every supercluster, every cosmic web filament we observe exists within our local bubble of observability, surrounded by regions forever beyond our observational reach.

This realization carries profound implications for cosmology and fundamental physics. The cosmological principle—the assumption that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic on large scales—can only be tested within our observable region. We must extrapolate these properties to the entire universe based on theoretical principles and the remarkable uniformity we observe in the cosmic microwave background.

Modern cosmological research continues to refine our understanding of expansion through increasingly precise measurements. Projects like the Dark Energy Survey map the large-scale structure of the universe to constrain expansion history and dark energy properties. Future missions will probe even deeper, potentially revealing whether our universe is finite or infinite, whether it has exotic topological properties, and whether the laws of physics remain constant across cosmic scales.

The expanding universe without center or edge challenges our intuitions precisely because it requires thinking beyond our evolved three-dimensional perspective. Yet by carefully examining dimensional analogies and recognizing the limitations of our observable bubble, we can grasp the essential truth: we inhabit a dynamic, evolving cosmos where every location is equally valid, and the very fabric of space itself participates in the grand cosmic expansion that began 13.8 billion years ago and continues accelerating today.