Our cosmic neighborhood may owe its current architecture to a dramatic encounter billions of years ago—a chance meeting with a rogue substellar object that wandered through the infant Solar System and forever altered the destinies of the giant planets. This provocative scenario, emerging from sophisticated computer simulations conducted by astrophysicists at the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Bordeaux and the Planetary Science Institute, offers a compelling explanation for one of planetary science's most enduring mysteries: what triggered the giant planet instability that reshaped our Solar System during its turbulent youth?

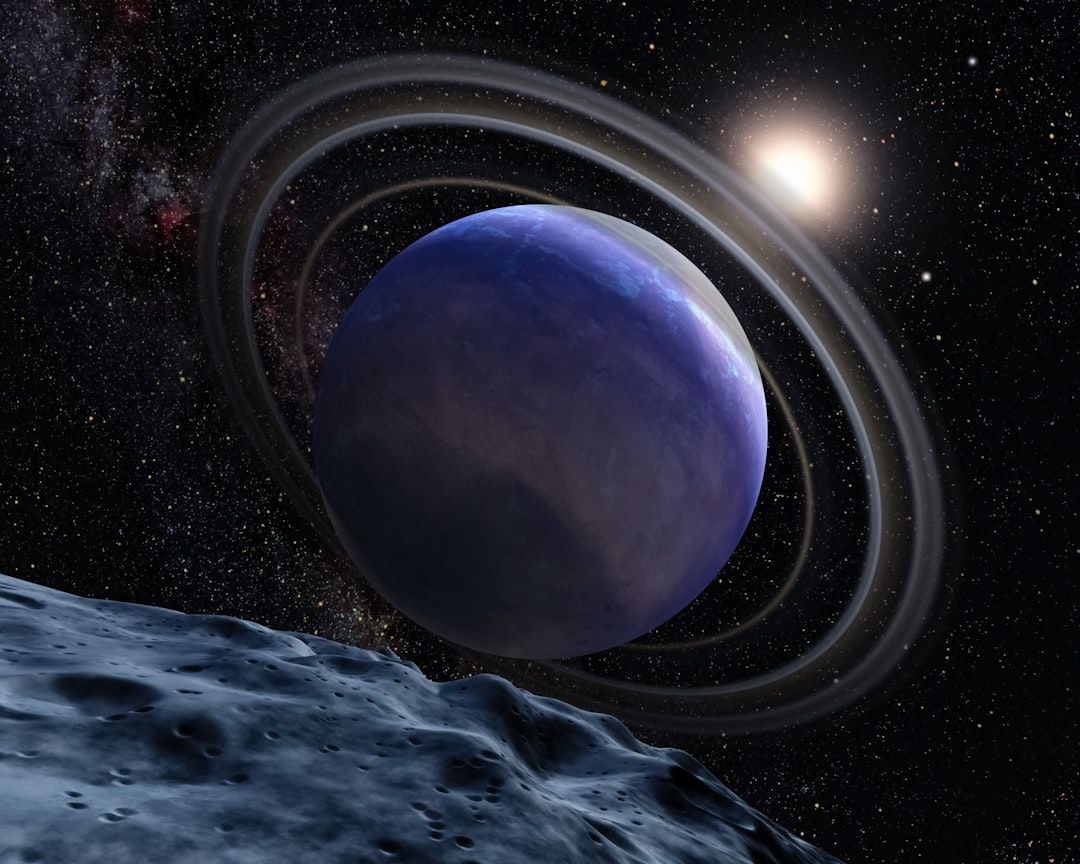

The evidence is written across the Solar System itself. Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—the four massive worlds that dominate the outer reaches of our planetary system—occupy positions that tell a story of ancient chaos and cosmic reorganization. These gas and ice giants didn't simply form where we observe them today; instead, they coalesced in a much more tightly packed arrangement before experiencing a violent gravitational upheaval that flung them outward to their present locations. This dramatic reshuffling left fingerprints throughout the Solar System, from the peculiar populations of Trojan asteroids that share Jupiter's orbit to the scattered debris of the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune's domain.

For decades, astronomers have recognized that such an instability must have occurred, but the fundamental question has remained frustratingly unanswered: What cosmic event could have destabilized an otherwise stable planetary configuration? Now, through an exhaustive series of 3,000 computer simulations, researchers Sean Raymond and Nathan Kaib propose that the culprit may have been a close encounter with a wandering brown dwarf or free-floating planet—a substellar vagrant passing through our Solar System during the Sun's formative years within a crowded stellar nursery.

The Architecture of Ancient Chaos

Understanding the giant planet instability requires appreciating just how profoundly it shaped the Solar System we inhabit today. This wasn't a minor perturbation but rather a fundamental reorganization of planetary architecture that occurred relatively early in Solar System history—most likely between 5 and 20 million years after the initial formation of the Sun and its surrounding protoplanetary disk. The timing constraint comes from analyzing ancient meteorites whose isotopic compositions preserve records of this tumultuous period.

The instability explains numerous otherwise puzzling features of our cosmic neighborhood. Consider Jupiter's Trojan asteroids—two vast swarms of rocky bodies trapped in gravitationally stable points 60 degrees ahead of and behind the giant planet in its orbit. These objects couldn't have formed where they currently reside; instead, they represent captured debris from the instability event itself. Similarly, the irregular satellites orbiting the giant planets in chaotic, highly inclined orbits bear the signatures of violent capture events rather than orderly formation.

Perhaps most tellingly, the structure of both the asteroid-belt" class="glossary-term-link" title="Learn more about Asteroid Belt">asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune reveal the scars of ancient gravitational violence. The Kuiper Belt, in particular, contains a population known as the "cold classical" objects—small bodies on nearly circular, low-inclination orbits that have remained essentially undisturbed since the Solar System's formation. These pristine objects serve as cosmic witnesses, constraining how violent any ancient encounter could have been while still preserving their delicate orbital configurations.

Simulating Stellar Encounters in a Cosmic Nursery

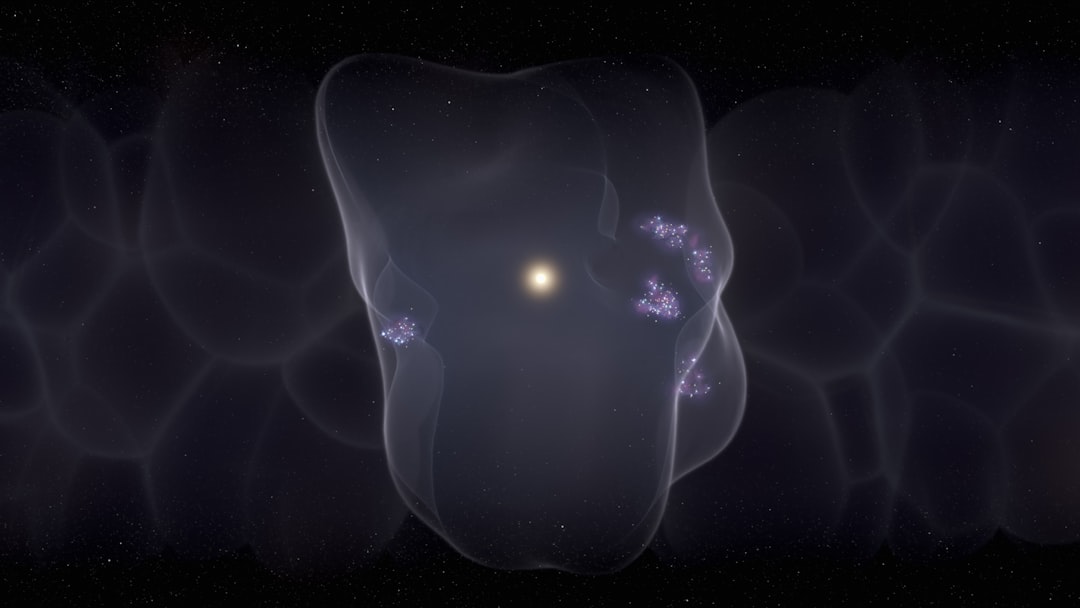

The Sun didn't form in isolation but rather within a stellar cluster containing hundreds to thousands of sibling stars—a crowded cosmic nursery where close encounters between stellar systems were not merely possible but inevitable. This realization forms the foundation of Raymond and Kaib's investigation into whether such encounters could have triggered the giant planet instability.

Their computational approach began with establishing initial conditions that reflected our best understanding of the early Solar System. Each of their 3,000 simulations started with the four giant planets arranged in a resonant chain—a gravitationally locked configuration where the orbital periods of adjacent planets maintain precise mathematical ratios. Left undisturbed, such configurations can remain stable for over 100 million years, far longer than the observed timing of the instability.

The research team then subjected each simulated planetary system to a single flyby event, systematically exploring a vast parameter space. The interloping objects ranged from relatively modest masses of just one Jupiter mass (roughly 318 times Earth's mass) up to genuine failed stars of ten solar masses. These objects passed at distances varying from extremely close approaches of just 1 astronomical unit (the Earth-Sun distance) out to remote encounters at 1,000 astronomical units. The encounter velocities spanned a range up to 5 kilometers per second—relatively slow by cosmic standards, reflecting the modest relative velocities expected within a young star cluster.

"The challenge was finding the sweet spot—flybys strong enough to destabilize the planetary system but gentle enough to preserve the delicate structures we observe today, particularly the cold classical Kuiper Belt objects that constrain how violent any encounter could have been," explains the research team in their published findings.

The Goldilocks Zone of Gravitational Disruption

The simulation results revealed a fascinating pattern. Very strong flybys—those involving massive objects passing extremely close to the planetary system—proved catastrophically destructive. These encounters either ejected planets entirely from the Solar System or excited their orbits into configurations bearing no resemblance to what we observe today. Conversely, very weak flybys—distant passages or encounters with low-mass objects—left the planetary system essentially undisturbed, failing to trigger any instability whatsoever.

But nestled between these extremes lay a "Goldilocks zone" of encounter parameters that produced remarkably Solar System-like outcomes. The successful scenarios shared distinctive characteristics that narrowly constrained the nature of any triggering flyby. The interloping object needed to be relatively low in mass, falling between 3 and 30 Jupiter masses—a range that places it firmly in the category of either brown dwarfs (failed stars lacking sufficient mass to sustain hydrogen fusion) or free-floating planets (planetary-mass objects unbound to any star).

Equally important, the object needed to pass within approximately 20 astronomical units of the Sun—close enough to directly perturb the giant planets themselves rather than merely stirring the outer disk of planetesimals. This relatively intimate encounter distance explains why such events, while potentially common in young stellar clusters, would leave lasting imprints on planetary system architecture.

The Statistical Challenge

Perhaps the most striking result emerged from the statistics: of the 3,000 simulations, only 20 successfully reproduced both the current orbital configuration of the giant planets and the preservation of the cold classical Kuiper Belt population. This represents less than one percent of all simulated encounters—a seemingly discouraging success rate that raises obvious questions about the plausibility of the flyby trigger hypothesis.

However, the probability calculation depends critically on factors that remain poorly constrained by observations. Chief among these is the abundance of free-floating planets and low-mass brown dwarfs in young stellar clusters. Recent observational surveys using facilities like the Very Large Telescope and space-based infrared observatories have revealed hints that these objects may be considerably more common than standard formation models predict.

The implications are profound: if the true abundance of substellar objects is underestimated by even a modest factor of four—well within observational uncertainties—the probability of a flyby-triggered instability rises from roughly one percent to approximately five percent. Given that the Sun formed within a cluster environment where such encounters were commonplace, a five percent probability becomes quite plausible over the relevant timescales.

Multiple Pathways to Planetary Upheaval

The flyby trigger scenario now joins a growing list of proposed mechanisms for initiating the giant planet instability, each with its own strengths and challenges:

- Gas disk dispersal: The dissipation of the primordial gas disk that surrounded the young Sun could have removed a stabilizing influence on the planetary orbits, allowing instabilities to develop. However, this mechanism struggles to explain the precise timing constraints.

- Spontaneous destabilization: Even without external triggers, resonant planetary configurations can become unstable over time through subtle gravitational interactions. The challenge lies in explaining why the instability occurred when it did rather than earlier or later.

- Planetesimal disk interactions: Gravitational interactions between the giant planets and the massive disk of icy planetesimals beyond Neptune's orbit could have gradually destabilized the system. This mechanism has gained considerable support but faces difficulties matching all observational constraints simultaneously.

- Stellar flyby trigger: The newly proposed mechanism offers the advantage of providing a specific, datable event that could explain the observed timing while preserving delicate structures like the cold classical Kuiper Belt.

Observational Tests and Future Directions

Distinguishing between these competing mechanisms represents one of the major challenges facing planetary science. Each scenario makes subtly different predictions about Solar System structure that might, in principle, be tested through sufficiently detailed observations and modeling. However, the passage of more than 4.5 billion years has erased or obscured many of the telltale signs that might definitively identify the trigger mechanism.

One particularly intriguing complication noted by the researchers is that even a flyby-triggered instability might not occur immediately after the encounter itself. The flyby could perturb the planetary system into a metastable configuration that remains apparently stable for tens of millions of years before finally succumbing to instability. This delayed response makes it even more challenging to connect cause and effect across billions of years of Solar System evolution.

Future research directions include more sophisticated simulations that incorporate additional physical processes, such as the detailed evolution of the planetesimal disk and the effects of planetary migration during the gas disk phase. Observations of exoplanetary systems at various evolutionary stages may also provide crucial insights. The James Webb Space Telescope and upcoming facilities like the Extremely Large Telescope will enable unprecedented studies of young planetary systems, potentially revealing whether instabilities triggered by stellar encounters represent a common phenomenon or a rare occurrence.

Implications for Planetary System Architecture

Beyond solving a specific puzzle about our own Solar System's history, this research carries broader implications for understanding planetary system architecture throughout the galaxy. If stellar flybys can trigger dramatic reorganizations of planetary systems, then the final configurations we observe today may reflect not only formation processes but also the chaotic histories of stellar cluster environments.

The work also highlights the importance of initial conditions and environmental factors in determining planetary system outcomes. Two planetary systems might begin with nearly identical configurations but end up looking dramatically different depending on whether they experienced disruptive encounters during their youth. This stochastic element—the role of chance encounters and random events—adds an additional layer of complexity to our understanding of how planetary systems form and evolve.

As we continue to discover and characterize thousands of exoplanetary systems through surveys like TESS and future missions, understanding the full range of processes that shape planetary architectures becomes increasingly important. The giant planet instability in our own Solar System may represent just one example of a common phenomenon—cosmic billiards played out in the crowded stellar nurseries where most stars are born.

Whether triggered by a wandering brown dwarf, the dispersal of primordial gas, or gravitational interactions with planetesimal disks, the giant planet instability stands as a pivotal event in Solar System history. It transformed a compact, orderly arrangement of worlds into the expansive, complex system we inhabit today—a system whose very structure preserves clues to dramatic events that unfolded when our Sun was still a youngster in a crowded stellar neighborhood, billions of years before the first stirrings of life on Earth.