In the golden age of exoplanetary science, astronomers have confirmed the existence of more than 6,000 alien worlds orbiting distant stars, fundamentally transforming our understanding of planetary systems throughout the cosmos. While this treasure trove of discoveries has revealed exotic planet types never seen in our own cosmic neighborhood—from scorching hot Jupiters to super-Earths—a fascinating question remains largely unexplored: How does the overall architecture of our Solar System compare to the broader structure of other planetary systems? Recent groundbreaking observations using the SPHERE instrument at the European Southern Observatory are now providing unprecedented answers, revealing that our Solar System may be far more typical than previously thought.

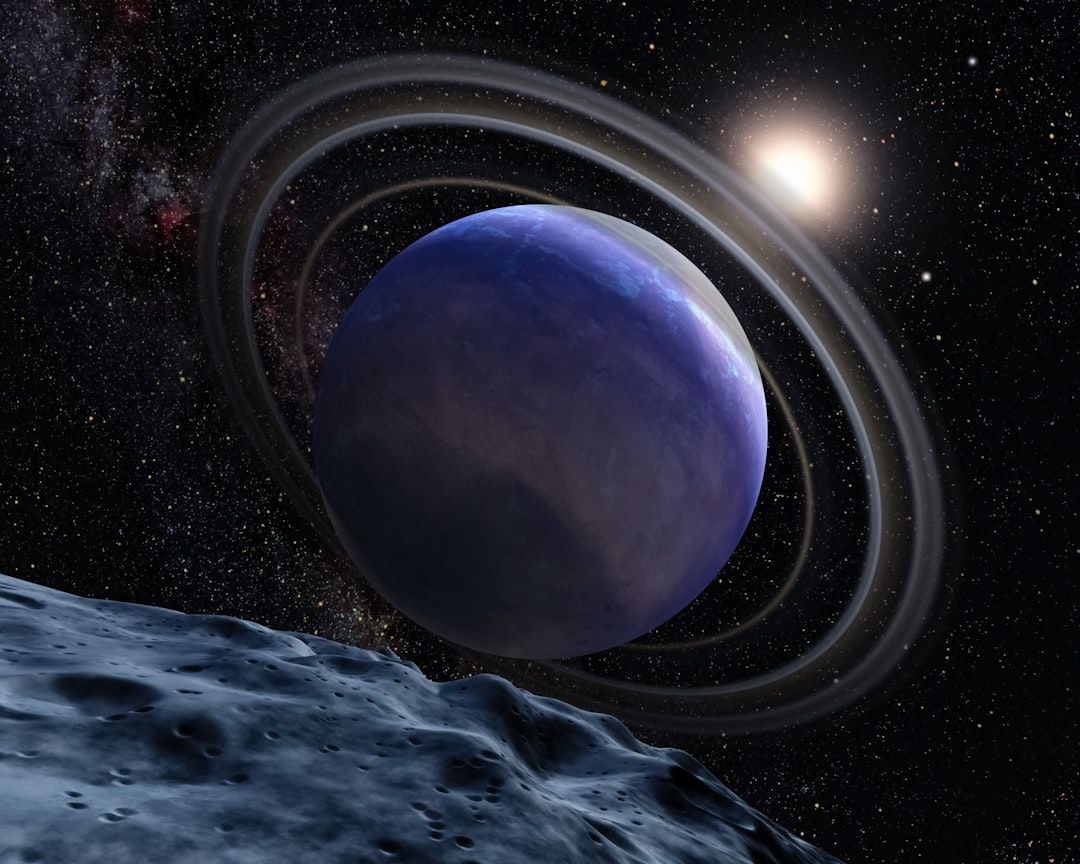

The key to understanding this cosmic commonality lies not just in the planets themselves, but in the intricate debris structures that surround stars—the circumstellar disks composed of leftover material from the violent, chaotic process of planet formation. These disk structures, analogous to our own Kuiper Belt and asteroid-belt" class="glossary-term-link" title="Learn more about Asteroid Belt">asteroid belt, contain critical clues about how planetary systems evolve and mature over billions of years. By examining these dusty remnants in 161 nearby stellar systems, an international team of researchers has compiled an astronomical treasure trove of data that illuminates the fundamental similarities between our cosmic home and countless other solar systems scattered across the galaxy.

The Hidden Architecture of Planetary Systems

When we think of a solar system, our minds naturally gravitate toward planets—those majestic worlds that capture our imagination and dominate astronomical headlines. However, the complete picture of any mature planetary system includes far more than just these prominent bodies. Between and beyond the planets lie vast regions populated by smaller objects: planetesimals, asteroids, comets, and debris that represent the building blocks left over from the system's formation approximately 4.6 billion years ago.

In our Solar System, these remnants are organized into distinct structures. The main asteroid belt, situated between Mars and Jupiter, contains millions of rocky bodies ranging from dust particles to Ceres, a dwarf planet nearly 1,000 kilometers in diameter. Further out, beyond Neptune's orbit, lies the Kuiper Belt—a frigid expanse of icy bodies including Pluto, which serves as a boundary marker for this distant region. This belt extends from approximately 30 to 55 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun and contains objects composed of frozen volatiles including water, methane, and ammonia, mixed with rocky material.

These debris structures are particularly fascinating to planetary scientists because they preserve a record of the planet formation process. Objects ranging from one kilometer to several hundred kilometers in diameter represent planetesimals that became "stuck" at that size—bodies that never accumulated enough mass to become full-fledged planets but were too large to be completely destroyed or dispersed. Understanding the distribution and properties of these objects across different stellar systems provides invaluable insights into the universal processes that govern planetary formation and evolution.

Revolutionary Observations with SPHERE Technology

Detecting and characterizing debris disks around other stars presents extraordinary technical challenges. The faint reflected light from dust particles and small bodies is completely overwhelmed by the brilliant glare of their host stars, making direct observation nearly impossible with conventional telescopes. Enter SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch), a sophisticated instrument mounted on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile's Atacama Desert.

SPHERE represents a technological marvel in modern astronomy, combining three powerful capabilities that work in concert to reveal otherwise invisible structures. First, its adaptive optics system compensates for atmospheric turbulence in real-time, producing images nearly as sharp as if the telescope were in space. Second, a coronagraph blocks out the overwhelming light from the central star, similar to how you might shield your eyes from the Sun to see nearby objects more clearly. Third, and perhaps most ingeniously, SPHERE employs polarimetry—analyzing the polarization state of light—to distinguish between direct starlight and light that has been scattered by dust particles in the circumstellar disk.

The new research, published in Astronomy and Astrophysics and led by Natalia Engler from ETH Zurich (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich), leveraged these capabilities to create an unprecedented gallery of debris disk images. The study processed observations of 161 nearby young stars whose infrared signatures strongly indicated the presence of substantial dust populations, successfully imaging 51 distinct debris disks with remarkable clarity and detail.

"This data set is an astronomical treasure. It provides exceptional insights into the properties of debris disks, and allows for deductions of smaller bodies like asteroids and comets in these systems, which are impossible to observe directly," explained co-author Gaël Chauvin from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, who also serves as a project scientist for SPHERE.

The Life Cycle of Circumstellar Dust

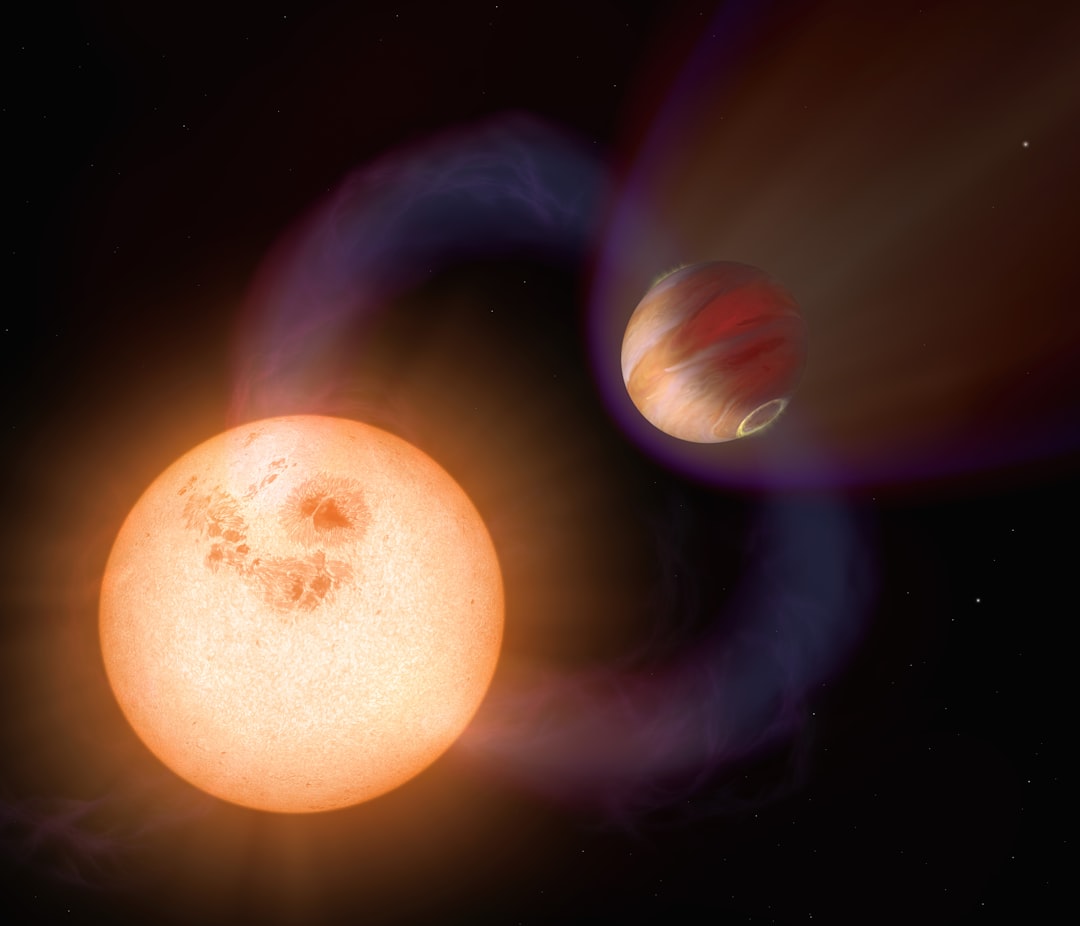

To fully appreciate these observations, we must understand the evolutionary timeline of debris disks. When a planetary system first forms from a collapsing cloud of gas and dust, the environment is extraordinarily chaotic and dust-rich. During the first 50 million years—the planet formation epoch—countless planetesimals collide with tremendous frequency, grinding material down into fine dust that permeates the entire system. This primordial dust reflects significant amounts of starlight, though the star's own brilliance typically drowns it out from our perspective.

As the system matures, several processes work to clear away this dust. Radiation pressure from the star pushes smaller particles outward and eventually out of the system entirely. Larger planets, through their gravitational influence, sweep up material or eject it from stable orbits. The collision rate decreases as planetesimals are either incorporated into planets, ejected from the system, or reach relatively stable orbits. Eventually, systems reach a state similar to our own Solar System, where leftover bodies are confined to distinct, well-defined rings with relatively clear gaps between them.

The zodiacal dust we observe in our Solar System today—the faint glow visible from dark locations before sunrise or after sunset—represents a steady-state population continuously replenished by asteroid collisions and cometary activity, but far less dense than the primordial dust that once choked our young Solar System. This evolutionary progression from dust-choked youth to organized maturity appears to be a universal feature of planetary system development.

Remarkable Diversity and Surprising Similarities

The SPHERE observations revealed debris disks with extraordinary variety in their properties and orientations. Some appear small and compact, while others extend across vast distances. Some are viewed nearly edge-on, appearing as thin lines, while others are seen face-on, revealing their full circular or elliptical structure. Four of the imaged disks had never been photographed before, adding entirely new systems to our catalog of known debris structures.

Among the 51 imaged systems, several key patterns emerged from the data analysis. The research demonstrated that more massive stars tend to harbor more dust in their circumstellar environments, likely due to more vigorous planet formation processes and higher collision rates among remaining planetesimals. Additionally, debris disks located at greater distances from their host stars contain more dust, possibly because outer regions experience less efficient dust removal mechanisms and preserve more primordial material.

Most intriguingly, the observations revealed that many of these alien solar systems exhibit concentric ring-like structures strikingly similar to our own asteroid belt and Kuiper Belt configuration. These rings represent regions where disk material concentrates at specific distances from the star, with relatively clear gaps in between. The images of systems like HD 106906, located approximately 340 light-years away, and HR 4796, situated about 235 light-years distant, showcase the remarkable level of structural detail achievable with SPHERE's advanced capabilities.

The Fingerprints of Hidden Planets

Many of the observed disk structures display features that cannot be explained by dust dynamics alone—they require the gravitational influence of planets to sculpt and maintain them. Sharp inner edges to debris rings, distinct gaps carved through otherwise continuous disks, and asymmetric features all point to the presence of massive planets shepherding the smaller bodies into specific orbital configurations.

In some cases, these planets have already been directly detected through other observation methods. Giant planets with masses comparable to Jupiter or Saturn can create dramatic gaps in debris disks, clearing out zones through their powerful gravitational fields. However, the researchers' dynamical modeling suggests that many of the observed structures require planets that remain below current detection thresholds—worlds with masses between Neptune and sub-Jovian scales orbiting at distances of tens to hundreds of astronomical units from their stars.

The modeling work proved particularly revealing for systems displaying multiple distinct rings. For single-belt systems, the team calculated that planets capable of shaping the sharp inner edges would span masses from 0.1 to 13 Jupiter masses, with orbital distances consistent with the observed disk boundaries. For two-belt systems—those with both inner and outer debris rings separated by significant gaps—the analysis indicated that sub-Jovian mass planets could create the observed structures while remaining undetectable with current technology.

"These findings imply that Neptune- to sub-Saturn-mass planets at tens to hundreds of AU may be common but remain undetected," the authors explain in their research paper, highlighting a potentially vast population of undiscovered worlds lurking in the outer reaches of nearby planetary systems.

Our Solar System in Cosmic Context

The most profound conclusion emerging from this comprehensive survey is that our Solar System's architecture appears remarkably typical rather than exceptional. The comparison of planetary architectures across the sample reveals that most benchmark systems resemble our own cosmic neighborhood, featuring multiple planets located interior to wide Kuiper Belt analogues. This finding contradicts earlier speculation that our Solar System might represent an unusual or atypical configuration.

This similarity extends beyond just the presence of debris belts to include their detailed structure and the implied presence of planets at various distances. The research suggests that the basic organizational principles governing our Solar System—inner rocky planets, outer gas giants, and distant debris belts—may represent a common outcome of the planet formation process under a wide range of initial conditions.

The study's findings have important implications for understanding planetary system formation and evolution as universal processes. The fact that similar structures arise around stars with different masses, ages, and metallicities suggests that the fundamental physics of planet formation produces predictable, repeatable outcomes. This predictability, in turn, helps astronomers refine their models of how planetary systems form and evolve over billions of years.

Future Directions and Expanding Horizons

While the SPHERE observations represent a major advance in our understanding of debris disk structures, they also highlight how much remains to be discovered. Future observations with next-generation facilities promise to refine and expand these results dramatically. The James Webb Space Telescope, with its unprecedented infrared sensitivity, can detect thermal emission from dust grains and potentially characterize their composition and size distribution in ways impossible from ground-based observatories.

Similarly, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile provides complementary capabilities, imaging debris disks at longer wavelengths where larger dust grains and even pebble-sized objects contribute to the observed emission. By combining observations across multiple wavelengths—from visible light through infrared to millimeter wavelengths—astronomers can build comprehensive models of debris disk properties, including the full size distribution of particles from microscopic dust to kilometer-scale planetesimals.

The research team emphasizes that expanding these multiwavelength approaches, together with advancements in disk modeling techniques and dynamical simulations, is essential for refining our understanding of debris disk evolution and the architectures of planetary systems. Future surveys will likely discover additional planets through direct imaging, particularly as instruments improve and observation strategies become more sophisticated. Each newly detected planet provides crucial constraints on system architecture and helps validate the predictions made by dynamical modeling.

Implications for Planetary Habitability

Understanding debris disk structures and the planets that shape them also has important implications for the search for habitable worlds. The architecture of a planetary system—the spacing and masses of its planets—influences whether potentially habitable rocky worlds can maintain stable orbits over billions of years. Additionally, the population of comets and asteroids in outer debris belts may play a crucial role in delivering water and organic compounds to inner rocky planets, potentially seeding them with the ingredients necessary for life.

Systems with architectures similar to our own, featuring outer ice giant planets and distant debris belts, may be particularly favorable for maintaining habitable conditions on inner rocky worlds. The ice giants serve as gravitational shields, deflecting many dangerous impactors away from the inner system while still allowing some comets to make the journey inward, potentially delivering volatiles to otherwise dry terrestrial planets.

A Universal Story of Planetary Formation

The SPHERE debris disk survey represents far more than a collection of beautiful images—it provides compelling evidence that the processes shaping our Solar System operate throughout the galaxy. The fundamental similarities in debris disk structures, the ubiquity of multiple ring systems, and the implied presence of planets at various orbital distances all point to planet formation as a robust, predictable process that produces similar outcomes under diverse conditions.

This universality is both humbling and exciting. It suggests that the basic architecture we see in our Solar System—the arrangement that allowed Earth to form in a stable orbit at the right distance from the Sun to support liquid water and, eventually, life—may be replicated countless times throughout the Milky Way galaxy. As our observational capabilities continue to improve and our surveys expand to include thousands of additional systems, we will undoubtedly discover both the common patterns and the fascinating variations that make each planetary system unique while still following the same fundamental rules.

The work by Engler and her colleagues demonstrates the power of combining cutting-edge instrumentation with comprehensive surveys and sophisticated modeling. By studying the dust and debris that most astronomers might dismiss as mere leftovers, they have illuminated the fundamental processes that govern planetary system architecture throughout the cosmos—and shown us that, in the grand scheme of the universe, our Solar System is both wonderfully typical and uniquely precious as our home.