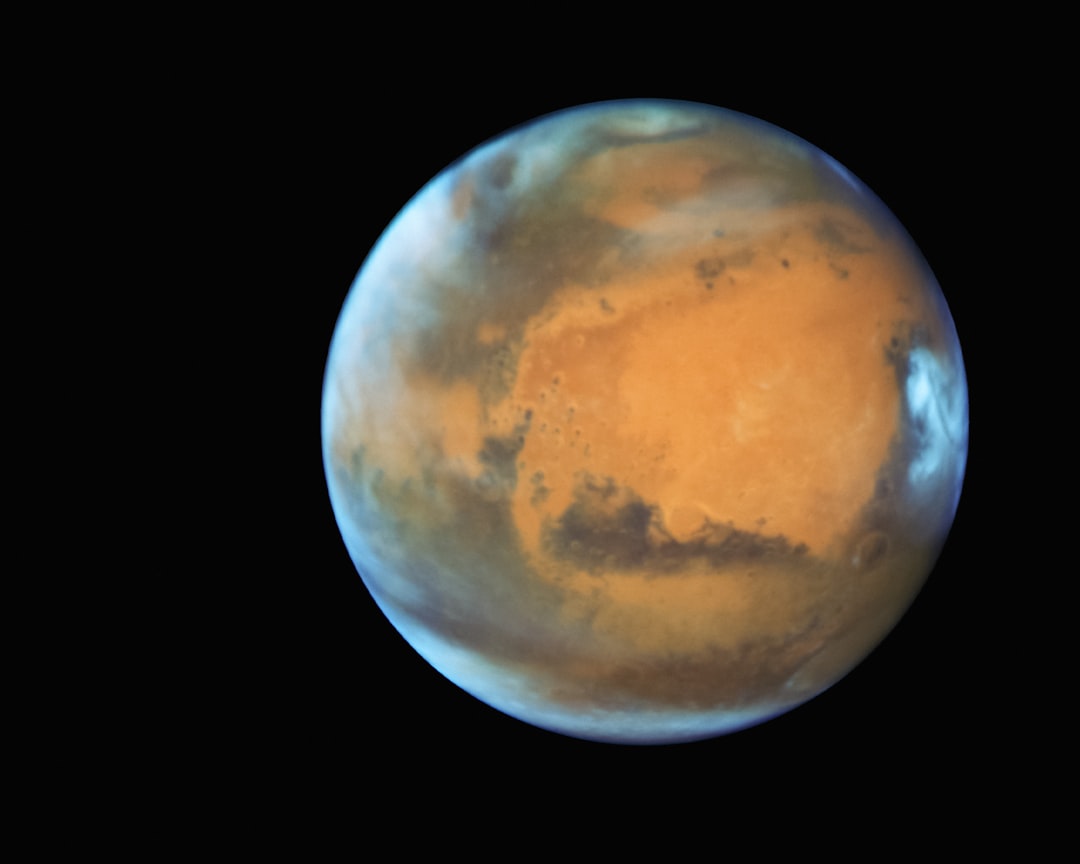

The quest to determine whether Earth-like worlds orbit nearby stars has taken a fascinating turn with new observations of TRAPPIST-1e, a rocky exoplanet situated in the habitable zone of an ultracool red dwarf star. Recent data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed tantalizing hints that this world might possess a methane-rich atmosphere, though researchers emphasize the need for cautious interpretation of these preliminary findings. Located approximately 39 light-years from Earth, the TRAPPIST-1 system has captivated astronomers since its discovery, offering a unique laboratory for studying potentially habitable worlds around the most common type of star in our galaxy.

The TRAPPIST-1 planetary system stands out as one of the most remarkable discoveries in exoplanet science. When astronomers confirmed the presence of seven Earth-sized rocky planets orbiting this diminutive red dwarf in 2017, using both the ground-based TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope in Chile and NASA's now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope, the scientific community recognized the system's extraordinary potential. What makes TRAPPIST-1 particularly compelling is that three of its seven planets—designated TRAPPIST-1d, e, and f—orbit within or near the star's habitable zone, the region where liquid water could theoretically exist on a planet's surface. Among these candidates, TRAPPIST-1e occupies the prime real estate, sitting squarely within the habitable zone's boundaries.

The latest investigation, conducted through the Deep Reconnaissance of Exoplanet Atmospheres using Multi-instrument Spectroscopy (DREAMS) campaign, represents a significant milestone in our ability to characterize small, rocky exoplanets. This ambitious research program has been leveraging JWST's powerful Near InfraRed Spectrograph (NIRSpec) to probe the atmospheric properties of terrestrial worlds orbiting M-type dwarf stars. Between mid-2023 and late 2023, the telescope captured light from TRAPPIST-1e during four separate planetary transits, gathering spectroscopic data that could reveal the chemical composition of any atmosphere the planet might possess.

Understanding the Atmospheric Detection Challenge

Dr. Sukrit Ranjan, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and co-author of the research published in three papers in the Astrophysical Journal Letters between September and November, articulated the fundamental question driving this investigation. The research team's primary objective centers on a deceptively simple yet profound inquiry: does TRAPPIST-1e even possess an atmosphere? This question carries enormous implications, as Ranjan explained in the research findings.

"The basic thesis for TRAPPIST-1e is this: If it has an atmosphere, it's habitable. But right now, the first-order question must be, 'Does an atmosphere even exist?'"

The technique employed by the research team involves capturing transit spectra—detailed analyses of starlight that passes through a planet's atmosphere during its transit across the face of its host star. When light filters through atmospheric gases, different molecules absorb specific wavelengths, creating a unique spectral fingerprint. This method can not only confirm the presence of an atmosphere but also identify its chemical constituents, potentially revealing biosignature gases such as oxygen, water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane that might indicate biological activity.

However, studying planets around red dwarf stars presents unique challenges. Unlike our Sun, which is a bright, yellow G-type star, TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool red dwarf—significantly smaller, cooler, and dimmer than our home star. These characteristics create both opportunities and obstacles for atmospheric characterization. The star's cooler temperature allows gas molecules to exist in its own atmosphere, which can contaminate the spectral signals scientists are trying to detect from the planet's atmosphere.

Decoding the Methane Mystery

The Telescope Scientist Team's initial findings, detailed in their first research paper, revealed intriguing spectroscopic features that suggested the possible presence of methane (CH₄) in TRAPPIST-1e's atmosphere. Methane is particularly interesting to astrobiologists because on Earth, it can be produced by both biological processes (such as microbial life) and geological activity. However, the team immediately recognized a critical complication: the level of stellar contamination they observed was consistent with previous studies of other planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system, though their observations covered a wider wavelength range.

Through sophisticated data analysis techniques, the researchers were able to marginalize—or account for—the contamination features in their spectra. This process allowed them to confidently rule out one possibility: TRAPPIST-1e does not possess a cloudy, hydrogen-dominated atmosphere like those found around gas giants. This finding itself represents important progress, as it narrows down the range of possible atmospheric compositions.

The team's second paper delved deeper into the methane hypothesis, conducting detailed simulations to explore what TRAPPIST-1e might look like if it indeed harbors a methane-rich secondary atmosphere. The most plausible scenario they identified—though researchers stress it remains statistically unlikely—envisions TRAPPIST-1e as a "warm exo-Titan," possessing an atmosphere similar to Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Titan's atmosphere is dominated by nitrogen with significant methane content, creating a thick, hazy envelope that has fascinated planetary scientists for decades.

The Stellar Contamination Conundrum

Dr. Ranjan highlighted the central dilemma facing the research team in interpreting their observations:

"While the sun is a bright, yellow dwarf star, TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool red dwarf, meaning it is significantly smaller, cooler, and dimmer than our Sun. Cool enough, in fact, to allow for gas molecules in its atmosphere. We reported hints of methane, but the question is, 'Is the methane attributable to molecules in the atmosphere of the planet or in the host star?'"

This question underscores one of the most significant challenges in exoplanet characterization. When observing small, rocky planets around red dwarf stars, scientists must carefully disentangle the spectral signatures originating from the planet's atmosphere from those produced by the star itself. Red dwarfs like TRAPPIST-1 are known to have complex atmospheres with molecular bands that can mimic or obscure planetary atmospheric features.

Statistical Analysis and Scientific Caution

In their third paper, the research team demonstrated exemplary scientific rigor by emphasizing the theoretical and statistical nature of their interpretation. Using Bayesian analysis—a sophisticated statistical framework that allows researchers to update their confidence in different hypotheses as new evidence emerges—the team reassessed their initial findings. Their revised analysis suggests a sobering conclusion: the tentative hint of a methane atmosphere they initially detected is more likely to be "noise" from the host star rather than a genuine planetary atmospheric signal.

However, this does not represent a definitive answer. As Ranjan carefully explained, "This does not mean that TRAPPIST-1e does not have an atmosphere – we just need more data." This statement encapsulates the iterative nature of scientific discovery, particularly in the challenging realm of exoplanet atmospheric characterization. The current observations represent an important step forward, but they highlight the need for additional observations and refined analytical techniques to reach more conclusive findings.

Revolutionary Implications for Exoplanet Science

Despite the ambiguous nature of the current results, this research represents a crucial milestone in humanity's quest to characterize potentially habitable worlds beyond our solar system. The JWST was designed and built long before astronomers knew that Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of nearby stars were common. The telescope's ability to study these worlds at all represents a remarkable achievement in astronomical engineering and scientific ingenuity.

The research team has identified only a handful of Earth-sized planets for which JWST could potentially measure detailed atmospheric composition. TRAPPIST-1e stands among this elite group, making every observation of this world scientifically precious. The techniques being developed and refined through these observations will inform future studies of similar worlds and help astronomers understand which planets warrant the most intensive follow-up investigations.

Key Findings and Methodological Advances

- Atmospheric Constraints: The observations definitively ruled out a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere, narrowing the range of possible atmospheric compositions for TRAPPIST-1e

- Methane Detection Hints: Spectroscopic analysis revealed potential methane signatures, though stellar contamination prevents definitive confirmation at this time

- Statistical Framework: The team developed rigorous Bayesian analysis methods to quantify confidence levels in different atmospheric scenarios

- Stellar Contamination Modeling: Researchers created sophisticated models to separate stellar atmospheric features from potential planetary signals

- Observational Strategy: Four separate transit observations provided multiple data points for cross-validation and consistency checking

Future Missions and Technological Advances

The path forward for definitively characterizing TRAPPIST-1e's atmosphere will likely involve multiple next-generation space missions working in concert. NASA's Pandora mission, currently in development and scheduled for launch in early 2026, will play a crucial role in this effort. This small satellite mission, led by planetary scientists from the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory, is specifically designed to monitor stars with potentially habitable planets during transits, helping to disentangle stellar contamination from planetary atmospheric signals.

Looking further ahead, the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) represents NASA's next flagship mission in the search for life beyond Earth. This large infrared/optical/ultraviolet space telescope is being designed specifically to search for biosignatures on exoplanets. Unlike JWST, which was built before the exoplanet revolution fully unfolded, HWO will incorporate lessons learned from current observations and will be optimized for characterizing potentially habitable worlds.

In the nearer term, the DREAMS collaboration is pioneering an innovative observational technique called dual transit spectroscopy. This method involves observing TRAPPIST-1 during simultaneous transits of two planets—TRAPPIST-1e and TRAPPIST-1b. By comparing the spectral features observed during these overlapping transits, astronomers hope to better separate stellar atmospheric effects from genuine planetary signals. This technique could prove invaluable for studying small, rocky planets around red dwarf stars, a category that represents the most common planetary systems in our galaxy.

Broader Context in the Search for Habitable Worlds

The TRAPPIST-1 system has become a cornerstone of comparative exoplanetology—the study of how planetary systems form, evolve, and potentially harbor life. With seven Earth-sized planets in a compact orbital configuration, the system offers unprecedented opportunities to study how planets with similar sizes and compositions can develop differently based on their distance from their host star and other environmental factors.

Recent studies using various space telescopes, including observations by the European Space Agency's contributions to JWST, have examined multiple planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. These comparative studies help scientists understand the range of possible atmospheric outcomes for rocky planets around red dwarf stars, which are crucial because M-type dwarfs comprise approximately 75% of all stars in the Milky Way galaxy.

Dr. Ranjan emphasized the pioneering nature of this work in his assessment of JWST's capabilities:

"It was designed long before we knew such worlds existed, and we are fortunate that it can study them at all. There is only a handful of Earth-sized planets in existence for which it could potentially ever measure any kind of detailed atmosphere composition. These observations will allow us to separate what the star is doing from what is going on in the planet's atmosphere – should it have one."

The Road Ahead: Persistence and Precision

The tentative nature of the current findings underscores an important reality in modern astronomy: extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The detection of an atmosphere on a rocky exoplanet in the habitable zone, particularly one that might contain biosignature gases, would represent one of the most significant discoveries in human history. Consequently, the scientific community maintains rigorous standards for such claims, requiring multiple independent confirmations and exhaustive analysis to rule out alternative explanations.

The ongoing observations of TRAPPIST-1e represent just the beginning of what will likely be a multi-year, multi-mission effort to definitively characterize this intriguing world. Each new observation adds to our understanding, whether it confirms previous findings, rules out certain scenarios, or introduces new puzzles to solve. The development of new analytical techniques, such as the dual transit method, demonstrates the creativity and persistence of the astronomical community in pushing the boundaries of what's possible with current technology.

As JWST continues its mission and new observatories come online, the dream of definitively detecting and characterizing atmospheres on Earth-like exoplanets moves closer to reality. The TRAPPIST-1 system, with its seven rocky worlds conveniently arranged for study, will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of this research. Whether TRAPPIST-1e ultimately proves to have a methane-rich atmosphere, a different atmospheric composition, or no atmosphere at all, the journey to find out is revolutionizing our understanding of planetary systems and our place in the cosmos.

The quest to answer the age-old question "Are we alone?" continues, one careful observation and rigorous analysis at a time. TRAPPIST-1e may yet reveal its secrets, but only through the patient application of cutting-edge technology, innovative methodology, and unwavering scientific scrutiny.