In the quiet laboratories of gravitational wave observatories scattered across the globe, humanity continues to eavesdrop on the universe's most cataclysmic events. Gravitational waves—ripples in the very fabric of spacetime predicted by Einstein over a century ago—carry messages from cosmic collisions so violent they defy imagination. When black holes or neutron stars spiral together billions of light-years away, their final moments of merger send tremors through spacetime that eventually wash over Earth, stretching and compressing space by distances far smaller than the width of a proton. The LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory), Virgo, and KAGRA detectors exist solely to capture these impossibly faint whispers from the cosmos, and their latest observation campaign has proven to be nothing short of revolutionary.

The Historic Fourth Observation Run: A Watershed Moment

The fourth observation run (O4), which commenced in May 2023 and concluded this month after more than two years of coordinated monitoring, represents a watershed moment in gravitational wave astronomy. During this extended campaign, the international collaboration detected approximately 250 new gravitational wave signals—a staggering achievement that accounts for over two-thirds of the roughly 350 gravitational waves discovered since the field's inception. To put this in perspective, the first gravitational wave detection occurred only in September 2015, marking the beginning of an entirely new era in observational astronomy. What began as a trickle of detections has now become a steady stream of cosmic revelations.

This dramatic increase in detection rates stems from steady improvements in detector sensitivity, achieved through years of painstaking engineering refinements and technological innovations. Enhanced laser power, improved mirror coatings, better seismic isolation systems, and advanced data analysis algorithms have collectively pushed the boundaries of what these instruments can detect. The observatories can now hear collisions occurring at greater cosmic distances and pick up fainter signals that would have been lost in the noise just a few years ago. Each incremental improvement in sensitivity exponentially increases the volume of space that can be monitored, and consequently, the number of detectable events.

Confirming Hawking's Prophecy: The Area Theorem Validated

Among the treasure trove of discoveries from O4, several events have already captured the attention of the global scientific community. Event GW250114 stands out as particularly significant, capturing two black holes merging with unprecedented clarity and providing the first observational confirmation of Stephen Hawking's area theorem from 1971. This theoretical prediction, one of Hawking's many profound contributions to our understanding of black holes, stated that the total surface area of black holes cannot decrease—a principle analogous to the second law of thermodynamics applied to these extreme objects.

"The validation of Hawking's area theorem through direct observation represents a monumental achievement in theoretical physics. We're not just detecting gravitational waves anymore; we're using them as precision instruments to test the fundamental laws governing the most extreme objects in the universe," noted Dr. Kip Thorne, Nobel laureate and LIGO co-founder, in a statement about the O4 results.

In the GW250114 collision, the initial black holes possessed a combined surface area of approximately 240,000 square kilometers—an area roughly equivalent to the United Kingdom. Following their merger, the resulting black hole measured approximately 400,000 square kilometers, representing a clear increase that validates Hawking's mathematical predictions. This observation provides crucial empirical support for our theoretical understanding of black hole thermodynamics and the deep connections between gravity, quantum mechanics, and information theory that Hawking's work illuminated.

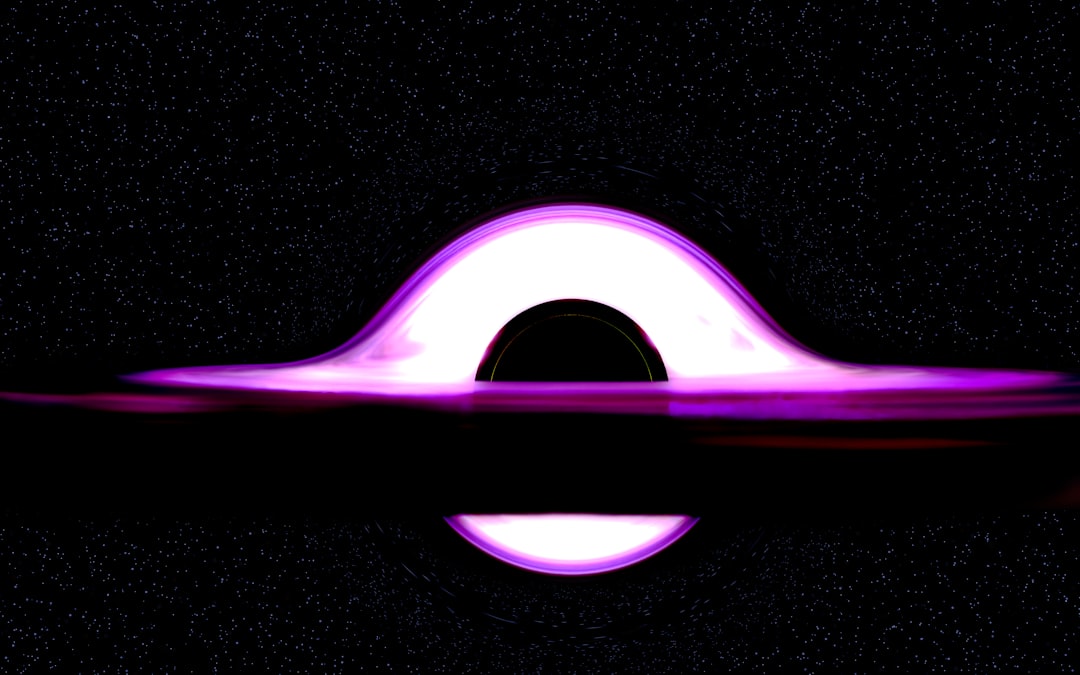

Understanding Black Hole Event Horizons

To appreciate the significance of this measurement, it's essential to understand what we mean by a black hole's "surface area." Unlike ordinary objects, black holes don't have solid surfaces. Instead, they're bounded by an event horizon—a mathematical surface marking the point of no return beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape the black hole's gravitational pull. The area of this event horizon is directly related to the black hole's mass and angular momentum, and according to NASA's black hole research, it serves as a fundamental measure of the black hole's entropy or disorder.

Second-Generation Black Holes: Cosmic Recycling at Its Most Extreme

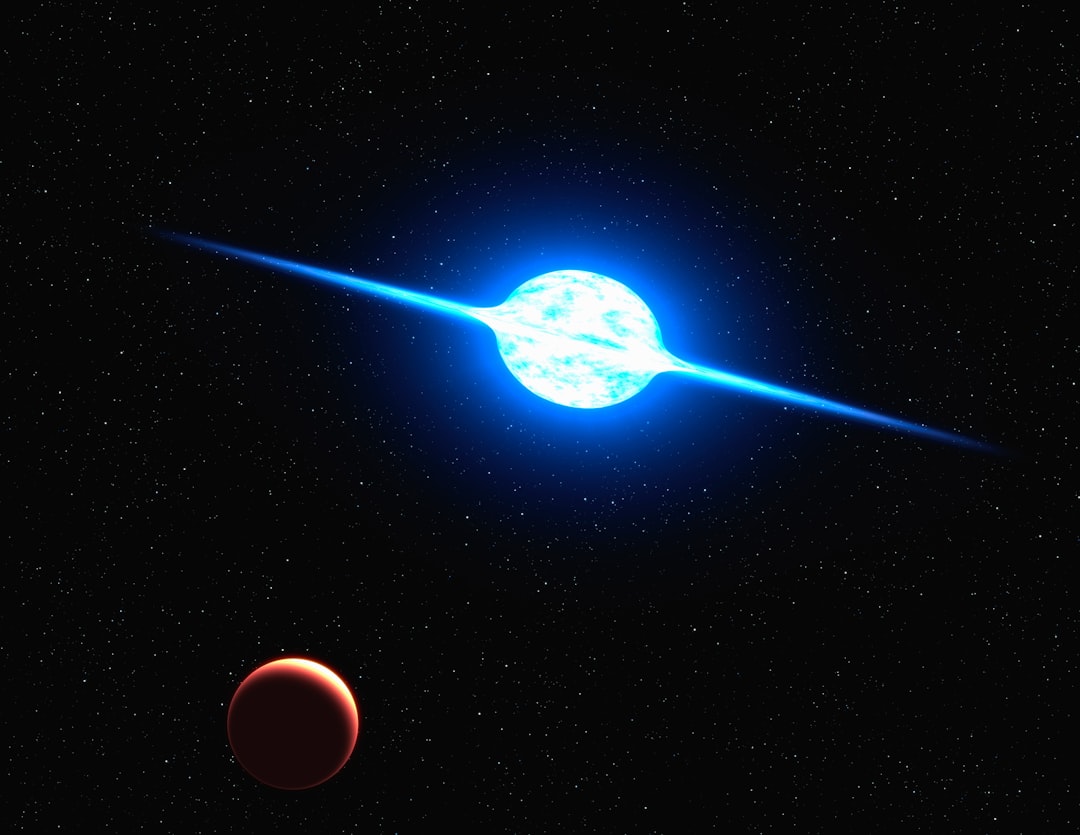

Perhaps even more intriguing than the Hawking theorem confirmation were events GW241011 and GW241110, which scientists have identified as likely examples of second-generation black holes. These objects exhibit unusual characteristics in their masses, spin rates, and rotational orientations that strongly suggest they're not pristine black holes formed directly from collapsing stars. Instead, they appear to be the products of previous mergers—black holes that have already consumed other black holes in earlier collisions.

These hierarchical merger systems likely formed in dense, chaotic environments such as globular clusters or the cores of active galaxies, where stellar densities are so extreme that black holes frequently encounter one another. In these cosmic mosh pits, black holes can collide and merge multiple times over millions of years, creating progressively larger objects through successive collisions. Each generation of merger produces a black hole with distinctive properties—particularly in its spin characteristics—that betray its complex formation history.

The Smoking Gun: Spin Misalignment

One of the key indicators that GW241011 and GW241110 represent second-generation mergers lies in the misalignment of their component spins. When black holes form directly from stellar collapse, they typically retain some of the angular momentum of their progenitor stars, and pairs that form together in binary systems tend to have aligned spins. However, black holes that form through previous mergers and then encounter new partners in dense stellar environments often show chaotic spin orientations. This spin misalignment serves as a cosmic fingerprint, revealing the tumultuous history of these objects. Research published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters has extensively explored these hierarchical merger scenarios and their observational signatures.

The Most Massive Merger: Pushing Theoretical Boundaries

The O4 campaign also detected GW231123, the most massive black hole merger observed to date. This cataclysmic collision produced a final black hole exceeding 225 solar masses—that is, more than 225 times the mass of our Sun compressed into a region of space just a few hundred kilometers across. This extreme result challenges current models of stellar evolution and black hole formation, particularly regarding what astronomers call the pair-instability supernova gap.

According to established theory, stars of certain masses should completely destroy themselves in pair-instability supernovae, leaving no remnant black hole behind. This process should create a "forbidden zone" in black hole masses, roughly between 50 and 120 solar masses. Yet increasingly, gravitational wave observations are revealing black holes that appear to fall within or exceed this theoretical gap. GW231123 adds to this growing puzzle, suggesting either that our models of stellar evolution need refinement or that alternative formation pathways—such as hierarchical mergers or black holes formed through direct collapse in the early universe—play a more significant role than previously thought.

The Technology Behind the Discoveries

The success of the O4 observation run rests on remarkable technological achievements. Each detector in the global network employs laser interferometry on a colossal scale. LIGO's two facilities in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, each feature L-shaped vacuum chambers with arms extending four kilometers in length. Ultra-stable laser beams bounce between precisely positioned mirrors at the ends of these arms, and when a gravitational wave passes through, it causes minute changes in the arms' relative lengths—changes that the instruments can measure with astonishing precision.

To detect the infinitesimal spacetime distortions caused by distant cosmic collisions, these observatories must overcome numerous sources of noise and interference. Seismic vibrations from traffic, ocean waves, and even logging operations hundreds of miles away can mask gravitational wave signals. Thermal noise in the mirror coatings, quantum fluctuations in the laser light itself, and countless other factors must be meticulously controlled or compensated for through sophisticated data analysis techniques. The European Space Agency's planned LISA mission will extend gravitational wave astronomy into space, where it can detect lower-frequency signals from even more massive cosmic events.

International Collaboration: A Global Network

The global nature of gravitational wave detection provides crucial advantages. With detectors on multiple continents operating simultaneously, scientists can:

- Triangulate source locations: By comparing the arrival times of gravitational waves at different detectors, researchers can determine the direction from which the signals originated, enabling follow-up observations with traditional telescopes

- Confirm detections: Multiple independent observations of the same event provide confidence that signals are genuine cosmic events rather than instrumental artifacts or local disturbances

- Characterize wave polarization: Different detectors with different orientations can measure various properties of the gravitational waves, providing richer information about the source events

- Maintain continuous coverage: When one detector undergoes maintenance or experiences technical issues, others continue monitoring, ensuring minimal gaps in observation

The Road Ahead: Future Enhancements and Expectations

While hundreds of additional events from O4 await detailed analysis—with researchers promising a comprehensive catalogue in the coming months—the three primary detectors are preparing for significant technological upgrades over the next few years. These improvements will be implemented in stages, with a new observation campaign, O5, scheduled to launch in late summer or early autumn 2026 for approximately six months initially.

The planned upgrades include enhanced laser systems with greater power and stability, improved quantum squeezing techniques to reduce quantum noise, better mirror coatings to minimize thermal noise, and more sophisticated data analysis algorithms powered by artificial intelligence and machine learning. These enhancements are expected to increase detection sensitivity by a factor of two or more, which would expand the observable volume of the universe by a factor of eight, potentially increasing detection rates to several events per day.

Multi-Messenger Astronomy: The Next Frontier

One of the most exciting prospects for future gravitational wave astronomy lies in multi-messenger observations—detecting the same cosmic event through multiple channels simultaneously. The 2017 detection of gravitational waves from merging neutron stars, accompanied by observations across the electromagnetic spectrum from gamma rays to radio waves, provided a spectacular demonstration of this approach. Such coordinated observations allow scientists to extract far more information about cosmic events than any single type of observation could provide alone. Future campaigns will emphasize rapid alert systems to notify conventional telescopes of gravitational wave detections, enabling prompt follow-up observations.

Implications for Fundamental Physics and Cosmology

The success of O4 demonstrates how gravitational wave astronomy has matured from detecting a handful of events to routinely monitoring collisions across the universe. This transformation has opened an entirely new window onto phenomena that remained invisible until just a decade ago. Beyond simply cataloging cosmic collisions, gravitational wave observations are providing unprecedented insights into fundamental physics and cosmology.

These observations allow scientists to test Einstein's general theory of relativity in the most extreme conditions imaginable—near black holes where gravity is so intense that spacetime itself becomes highly curved. So far, general relativity has passed every test with flying colors, but any deviation from its predictions would represent a revolutionary discovery pointing toward new physics beyond our current understanding.

Gravitational wave observations also offer a unique method for measuring the Hubble constant—the rate at which the universe is expanding—independent of traditional techniques. By analyzing the gravitational wave signals from binary neutron star mergers and comparing them with electromagnetic observations of the same events, astronomers can determine cosmic distances and expansion rates. This approach may help resolve the current "Hubble tension," a puzzling disagreement between different measurement methods that has emerged in recent years.

"We're witnessing the birth of a new field of astronomy that will continue to revolutionize our understanding of the universe for decades to come. Each new detection adds another piece to the cosmic puzzle, revealing the hidden dynamics of the universe's most extreme objects and events," emphasized Dr. Gabriela González, former spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.

Conclusion: A Universe Revealed Through Ripples in Spacetime

The conclusion of the O4 observation run marks not an ending but a milestone in an ongoing journey of cosmic exploration. With 250 new gravitational wave detections added to humanity's catalog of observed cosmic events, we stand at the threshold of an era when gravitational wave astronomy transitions from novelty to routine scientific tool. The discoveries made during this campaign—from confirming Hawking's area theorem to identifying second-generation black holes and detecting the most massive merger yet observed—demonstrate the extraordinary scientific potential of listening to the universe through gravitational waves.

As detector technology continues to advance and new observatories come online, the pace of discovery will only accelerate. The next generation of gravitational wave detectors, including the proposed Einstein Telescope in Europe and Cosmic Explorer in the United States, promise sensitivities orders of magnitude greater than current instruments. These future facilities will detect thousands of events per year, potentially observing the very first black holes formed in the early universe and providing unprecedented insights into cosmic history.

The universe speaks to us through many voices—visible light, radio waves, X-rays, neutrinos, and now gravitational waves. By learning to listen to all these cosmic messengers, humanity gains an ever more complete understanding of the cosmos we inhabit. The success of the O4 observation run reminds us that we live in an extraordinary age of discovery, when the universe's most violent and energetic events are no longer beyond our reach but instead become windows into the fundamental nature of reality itself.